Curator Yuji de Torres developed this proposal for the 2024 Curatorial Intensive in Indonesia.

In 1991, the West German band Scorpions released their hit song “Wind of Change,” which has been implicated in the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR. This proposal concerns the plurality of winds within the tumultuous period of the 1980s, as enacted through exhibition-making. From the militant ’70s towards the supposed end of history of the ’90s, the ’80s saw the rise of the conservative governments of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, as well as the fall of dictatorships in the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan.

At the heart of this research is my attempt to examine exhibitions and exhibition-making within the context of a protracted decolonization, particularly given the colonial origins of the exhibition form. From World’s Fairs in the metropoles—such as the Madrid Philippines Exposition in 1887 and the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904–both of which exhibited living native people from the Philippines alongside artworks and artifacts—to the harnessing of representation by fascist dictators, exhibitions in the postcolony became the ethical counterpoint to coercive regimes and instilled consent for their rule. Amid this context, this research attempts to constellate modes of exhibition-making that confronted the task of decolonizing the exhibition, particularly in the challenging milieu of the 1980s.

My research begins with Piglas (Liberate): Art at the Crossroads, an open-call exhibition that took place in 1986 at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP). Built on reclaimed land and funded by war reparations from the United States, the CCP was heralded by former First Lady Imelda Marcos as a pantheon of culture. In the ’70s and early ’80s, it was home to a group of young artists with a conceptualist bent, often criticized as being apolitical, working under the tutelage of artist-curator-educator Roberto Chabet and with encouragement from the CCP’s Museum Director, artist-curator Raymundo Albano. Elsewhere during the same time, the artist collective Kaisahan and the nationwide organization Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) nurtured the cultural front of the brewing anti-imperialist and anti-dictatorship movements. On the island of Negros, where sugar plantations continue to grow rampant and which experienced a famine in the ’80s after a crash of the global price of sugar, CAP-Negros organized cultural events and participated in exhibitions in Manila.

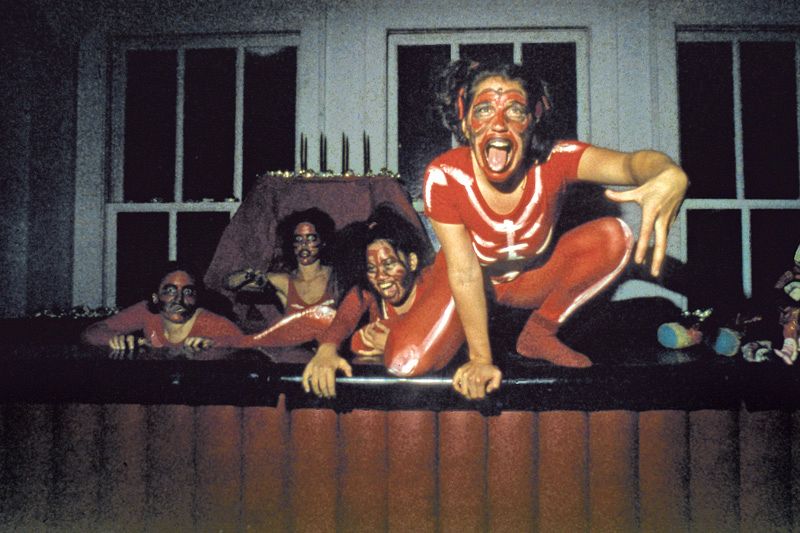

With the fall of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. by a popular uprising in February 1986, the CCP and similar cultural infrastructures built under his dictatorship became sites of contention. Opened on April 19, 1986, Piglas consisted of around 200 artworks including, crucially, works by the members of Kaisahan and CAP-Negros. For its opening night, the CCP opened its doors to street vendors selling peanuts, kroprek (fried prawn cracker), and balut (boiled or steamed fertilized duck egg). Art historian Patrick Flores characterized Piglas as “a scene akin to barbarians crashing the gates, a come-one, come-all invitation to a potluck party, as it were.” In the months that followed, critical and sympathetic exhibitions opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila and the now-defunct Museum of Philippine Art entitled Bagkus Bugkus and Artists for Peace, respectively.

This initial research was initiated through the support of the 2023 Emerging Writers Fellowship of the journal Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia. Using the Philippine context as a starting point, this research attempts to constellate exhibition-making in the 1980s as a polyphony—a series of propositions and dissents. This initial research is my attempt to extend the field of exhibition histories toward the Philippine context. While there have been many art historical texts about the Philippines penned by many great writers, there has yet to be an account of a singular exhibition in the Philippines, taking into account its colonial origin and its semi-feudal and semi-colonial context. Rather than an effort for representation, this research finds exhibitions in the mode of expression that sought to confront the exhibitionary history of the postcolony and imagine the world, and themselves, anew.