My exhibition proposal was halfway complete when I participated in the 2024 Curatorial Intensive in February–March. It was due in two and a half months. While those of us at the Komunitas Salihara—a private art center in Jakarta which comprises contemporary performing arts, literature and visual arts curatorial, and was founded in 2008—had decided on my project’s curatorial framework and its design was all set, the Intensive personally shifted my understanding of and relationship to the project quite fundamentally: How can we better communicate our project to our audience?

Within nine intensive days, the participants and ICI faculty members shared and learned the emotional, conceptual, and practical aspects of curating through mentoring, presentations, group discussions, and peer-to-peer learning. It was also the first time that the Intensive was held in two places, or should I say, chapters: Yogyakarta and Bali, two culturally rich yet very different regions for art in Indonesia. Yogyakarta is the home for spaces and practitioners who are deeply rooted in collectivism. Here, the Intensive program was mostly based in the Indonesian Visual Art Archive (IVAA). We also visited collective spaces including KUNCI Study Forum & Collective, Bakudapan, and Sekolah Pagesangan. Instead of seeing “art”, we saw practices and methodologies. KUNCI, for example, is a collective focusing on collectivism and pedagogy through research, library, press and publishing, and “school” organizing. The latter project is called The School of Improper Education, which explores alternative study methods through equal sharing instead of one-way, hierarchical teacher-student relations.

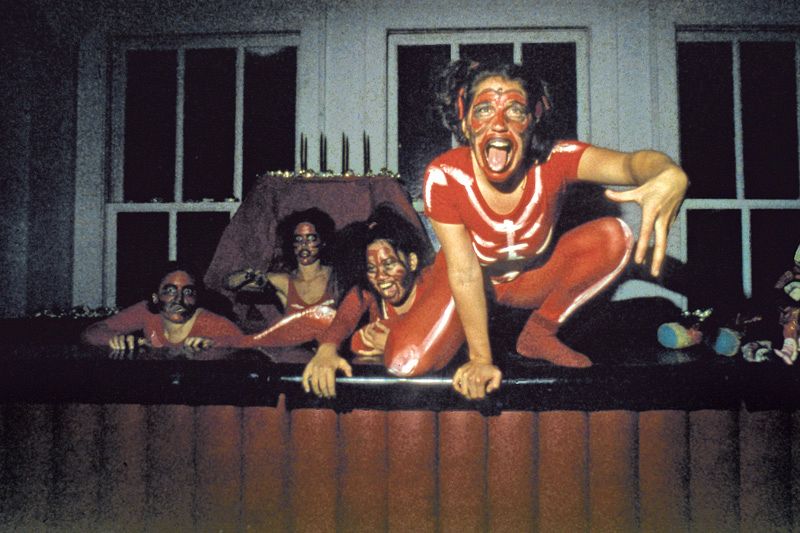

An afternoon at KUNCI where all the participants participated in one of KUNCI’s initiative The School of Improper Education. Photo: Ibrahim Soetomo, 2024.

The Yogyakarta chapter, for me, was also our chance to study through observing and witnessing each other’s curating practice. While in Bali, we had fewer visits and concentrated our workshop in Yayasan Bali Purnati, a performing arts producer and space. This chapter was the time for more foundational reflections, leading to group-based project presentations on the last day. Over the nine days, we all observed an increasing confidence from each participant in presenting and planning projects. The whole chapter led to a patient, cyclical process of learning and unlearning.

My project focused on six relief sculptures made by Indonesian modern artist groups in the 1950s–1960s in Java and Bali. Beginning in 2022, we at the Center shifted our visual art curatorial approach to be more historical, archive-based, and cross-disciplinary to balance our contemporary art exhibitions. We believe it is important to root ourselves in the history of intellectualism and nation-building, which is now often overlooked in current society. My project, titled Relief Era Bung Karno (Reliefs in Bung Karno’s Era; “Bung Karno” refers to Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno), is the fifth project in this ambitious trajectory. Positioning the relief art at the center, we delved into the dynamics of patronage, commissions, and monumentalism in public art, as well as nationalism. We conducted field research on actual relief sites, then processed it into a documentative exhibition format. For a while, I focused more on the relief medium itself. But after a session with faculty member and mentor Zoe Butt, I started to treat the relief artists (albeit all long deceased) as active agents, as storytellers, and as those who make legacies from which we can reap and pass knowledge. And that’s exactly one of the things I have learned: curating is storytelling. So, what kind of story would we like to convey?

A morning session with one of the faculty members, Zoe Butt, at Bali Purnati. Photo: Ibrahim Soetomo, 2024.