Reports from the Field are perspectives from curators from around the world, who are alumni of the Curatorial Intensive, ICI's professional development program for emerging curators. The commissioned texts are reflections on the impact of the global pandemic on their lives, ways of working, their communities, and how they are adapting as a response.

Pojai Akratanakul, Alumna of the Curatorial Intensive Bangkok '18, writes from Bangkok, Thailand. To read and download the PDF version, click here.

Empty Siam Square, a usually very crowded shopping area.

Everyone here has been very concerned about the coronavirus outbreak since late January when the first cases were detected in Thailand. But it really hit us at the beginning of March after the super-spread Muaythai boxing event at the Lumpini Stadium set off a chain of local cases. A few weeks later, the government declared a state of emergency, and by April the lockdown was implemented. Malls, cinemas, museums were closed, and all public gatherings restricted.

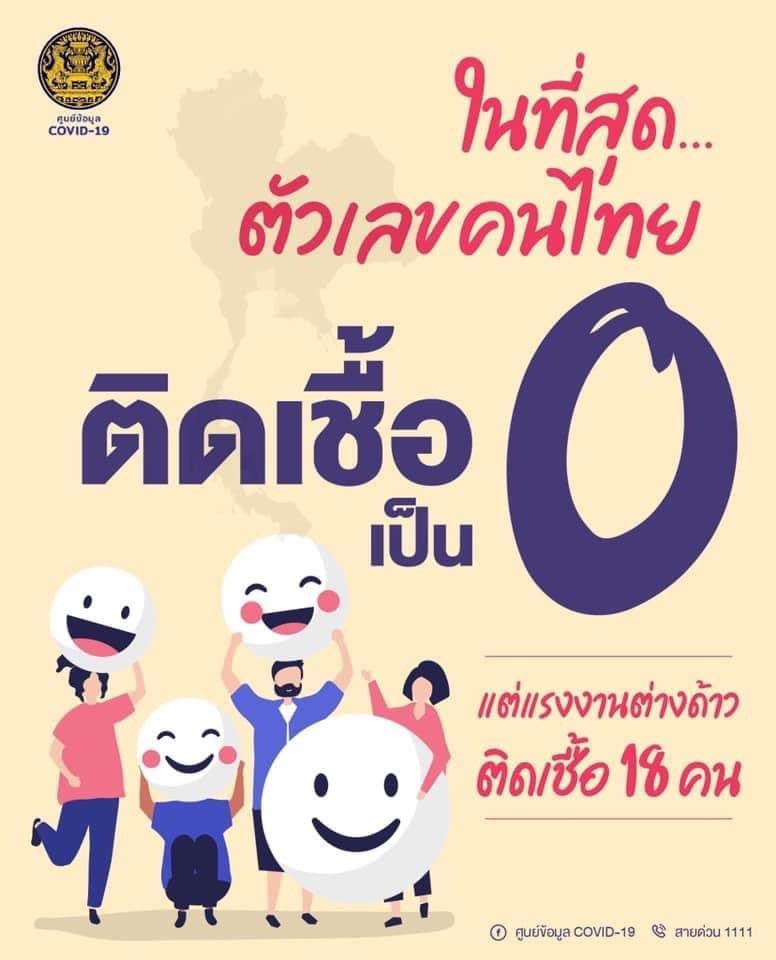

The Thai New Year holiday Songkran, usually taken very seriously by locals, was for the first time in history canceled to avoid social gatherings and stop people from returning to their hometowns. By then, we had been told repeatedly to “stay home, stop the virus, for the nation,” the slogan issued by the government’s COVID-19 Response Centre. The situation allowed nationalism to pride, or disguise itself as a solution. And in the mind of many, it has since been a fight of and for the “Nation.” May 4, the infographic released from the Centre announced “Finally Thais have 0 new infections!” And the second line in the smaller typeface reads “But 18 immigrants are infected.”

Despite their hard-to-believe attitude, the lockdown did help. Fourteen days later the number of daily new infections went down to a single digit. But it also puts many out of their jobs. Thailand’s biggest site for job search has reported that there is a big reduction of job posts especially the ones with lower wages. It was estimated that seven million jobs have been lost since the outbreak, and it would reach eleven million in the worst-case scenario. And nobody is certain when or if the “normalcy” will return.

Seeing these signs no doubt puts people in the local art industry on edge. Not only that, galleries, art centers, museums, are still closed. In the Bangkok art scene, already small and tight-knitted as it is, the artist’s career and questions of survival have been raised long before the coronavirus crisis. Jobs for art workers have always been scarce; let alone secure, well-paid ones. The majority of us have had unpaid art jobs while working paying jobs outside the arts field.

During the lockdown, many Bangkokians staying inside, including myself, are relying so much on takeouts and food delivery. Sending food and masks to friends has also become a new trend representing a gesture of care. Last week I delivered mangoes to six artists. Surprisingly, several young artists are now picking up pots and pans and setting up new businesses either for serious or for fun making sausages, bread, meal plans; and they are acing it. It reminded me of collectivistic contemporary art communities and how many of them formed around sharing food and eating together.

Some examples: The N22 community, a lofty compound that housed seven art galleries and artist studios, including Gallery VER founded by Rirkrit Tiravanija, is known for its barbecue parties at art openings; Bangkok CityCity Gallery hosted many great events featuring wonderful menus such as Dusadee Huntrakul’s Oxtail Rice Noodle Soup with Grilled Chilli; or the after-show ritual that artists and curators run for a late round-table dinner at a Chinese place in Silom followed by karaoke. All of this is now clearly impossible.

Bottled Cold Brew by designer-artist Lita Chala-adisai in front of Blessing poster designed by herself. Image Credit: Pongsakorn.

From the Tiger & Tomato kitchen: Hong Kong Beef with Tofu (beef belly braised in soy sauce & orange zest, with sesame oil & vinegar sauce), Atit Sornsongkram’s recipe; and Bitter Melon and Pork Rib Soup, Prae Pupityastaporn's recipe; served with rice.

Homemade Thai beef sausages by Yingyod Yenarkarn.

On the structural level, the local community of contemporary art has long been dependent on the money from a limited group of patrons, collectors, very little corporate sponsorship — and very little from the government. This is poised to change as many of these donors themselves were heavily affected by the crisis. The stagnation is expected to deprive art initiatives of its major funding, which could make this very tight-knit community even tighter.

One of the first groups of curators and artists that came together to respond to the crisis was the Surviving & Fighting COVID-19 Art Alliance (SFAA). They are taking their concerns to the government directly, and after conducting a survey with artists via Facebook, SFAA handed the Ministry of Culture a request for financial aid and strategic measures in supporting people in the arts, with a list of artists who were critically affected. The Ministry assured that the enlisted artists will be considered for a rescue package of 5,000 Baht (about 160 USD) per month but has stopped short on confirming if all or how many individuals will receive help. SFAA continues to push more proposals and strategic projects to further aid the community and is hoping to be able to eventually form an art council, one which the scene has never had yet.

The infographic released by the government’s COVID-19 Information Facebook page on May 4 says “Finally, Thais have 0 new infections,” then “But 18 immigrants are infected.” The image was shortly taken out of the page after it enrages the public.

The longer physical distancing continues the more social interaction takes place online. One of the noticeable trends on Facebook here was the emergence of these “alma-mater marketplaces.” For example, an alumnus of Chulalongkorn University created a “Chula Marketplace” for other alumni to exchange and advertise their businesses so that they can help one another. In these groups, you can purchase all kinds of things ranging from fermented fish to a plot of land on some private island. These online groups don’t exist merely for commercial purposes; they offer a sense of affiliation, at the moment when people want to feel that they ‘belong’ to a community, and this has been at the source of their popularity.

This applies to the art community, too. A group called “Thailand Art Ecosystem” was created by contemporary art and cultural workers with the intention to create a database of art professionals. It gained over 1,300 members overnight. But not long after, a few artists noticed that one of the group’s rules barred “political topics,” leading to some drama. A large number of contemporary artists who disagreed with the rule left the group which nevertheless continued to grow in number.1

Artists and art workers may be underpaid and isolated, but they just won’t cave in! It’s the spirit that reminds me very much of the old normal, pre-COVID-19.

A respected curator told me they think art for art’s sake won’t work anymore post-COVID-19. But where will art fit in society after the pandemic? Seeing those who suffered far worse than not being able to attend an art exhibition, I can not help but be reminded that art is a luxury, especially for this moment. What is more important now is survival (physical, mental, as well as economic). So, the least we can do is check in on our friends and colleagues to make sure they still feel they belong in the world at the time when “the art world” is temporarily suspended. For if they survive, we know they’ll find away.

Footnote:

1) The group later explained the rule exists just to avoid conflicts, but posting images of politically-charged art is acceptable. It is also interesting to note too that a huge number of artists who later joined come from modern and traditional practices.