Reports from the Field are perspectives from curators from around the world, who are alumni of the Curatorial Intensive, ICI's professional development program for emerging curators. The commissioned texts are reflections on the impact of the global pandemic on their lives, ways of working, their communities, and how they are adapting as a response.

PJ Gubatina Policarpio, Alumnus of the Curatorial Intensive New Orleans '18, writes from San Francisco, CA. To read and download the PDF version, click here.

Diversity Plaza, July 2018. Photo: PJ Gubatina Policarpio.

Dear Prof. Choy,

I’ve been thinking a lot about Queens. Primarily the neighborhoods of Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, and Corona, which has emerged tragically as the epicenter of a coronavirus outbreak in New York. Corona (and later Woodside) was my home from 2013-17. While my time there was brief, the largely migrant, working-class, multilingual, intergenerational community/ies along Roosevelt Ave and its ethos had a profound impact on my work as an educator and curator. In central Queens, I strengthened my foundation as a cultural worker and community organizer. At Diversity Plaza, I invited authors Gina Apostol, Mia Alvar, Hossannah Asuncion, and Queens writers Bino Realuyo, Paolo Javier, and Ninotchka Rosca to read their work. As Gina reminds me, it was the first time she’s shared her work in front of a busy beauty salon. This gathering led to the Pilipinx American Library, an itinerant collection of printed matter and programming platform dedicated exclusively to Filipinx perspectives.

Phayul’s, Jackson Heights. January 2020. Photo: PJ Gubatina Policarpio.

I am thinking about care and the brown body. In particular, I am thinking about the Filipinx body, those of Filipinx American nurses (and their families) in Elmhurst and in hospital wards and care centers the world over. When I first moved to Queens, I used to laugh remembering that common refrain among us Filipinxs in America: where there are hospitals there are surely Filipinxs around. During this global pandemic this refrain stings; knowing full well that Filipnx bodies carry the brunt of care and labor at the risk of their own lives. The stories are heartbreaking.

“Filipino American medical workers have suffered some of the most staggering losses in the coronavirus pandemic. In the New York-New Jersey region alone, ProPublica learned of at least 30 deaths of Filipino health care workers since the end of March and many more deaths in those peoples’ extended families. The virus has struck hardest where a huge concentration of the community lives and works. They are at “the epicenter of the epicenter,” said Bernadette Ellorin, a community organizer.” ProPublica

I am reminded of your critical work on Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History, making visible the complex account of Filipino nurses in America and the forever linking of two countries: the Philippines and the United States.

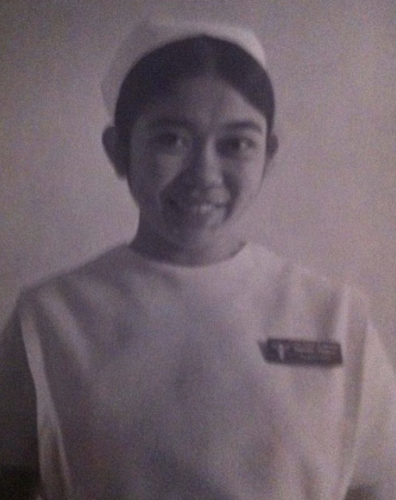

My own family’s American crossing is intrinsically connected to this history. In 1975, my aunt Consejo, my mother’s sister, flew on a one-way flight to New Jersey, where she was to work as a nurse. At 25, she traveled alongside many other young highly trained Filipina nurses, whose sought-after labor was necessary to fulfill critical shortages in U.S. hospitals. (Countering commonly peddled narratives of immigrants taking away American jobs.) In large part owing to my aunt’s labor, my mother’s sprawling family would slowly emigrate to the United States, including my own uprooting to San Francisco in 1998 at 13. I could see that she was happy when we finally arrived. My ma and pa and I decided to stay with her in Los Angeles for some time before life in the United States would officially take hold of us. She took us on the requisite “newcomers” tour: Disneyland, Universal Studios, plus a quick detour to Las Vegas. One day she took us to Hollywood Presbytarian, the hospital where she worked at the time. She was proud to be a nurse. She took pride in how her profession could make life better for her family. In 2005, my aunt would die of colon cancer in the Philippines.

Consejo Gubatina.

Just as we can’t tell the history of agriculture and the labor movement of the west coast without the story of Filipino farmworkers, we cannot tell the history of healthcare in the United States without the story of Filipina women. More fully, as the late historian Dr. Dawn Buholano-Mabalon reminds us all: “You can’t tell the story of labor, migration, and empire [in America] without the story of Filipino Americans.” As I write this letter sheltered-in-place here in San Francisco, I can’t help but ask how I can be of service to this place that has given so much to me. How can I support the nurses, health care providers, and essential workers in the front lines? Who cares for the caregivers?

*****************

Dear PJ,

It’s lovely to hear from you. I enjoyed reading about your personal connections to Filipino nurse migration. I love that photograph of your aunt!

I’ve been teaching Filipino American History at UC Berkeley for over 15 years, and the vast majority, if not all, of my students with Filipino heritage has an intimate connection to nursing. At least one of their relatives works or has worked as a nurse in the United States.

When I read about the Filipino nurses in the U.S. who have died as a result of their work on the COVID-19 frontlines, I am also filled with grief and heartbreak. It is so important to take time to grieve, to confront the enormity of this loss.

The other day I sat by the front windows of my home with my journal and pen in hand. And I started to write the names of some of the Filipino nurses in the U.S. who have died. Araceli Buendia Ilagan. Noel Sinkiat. Rosary Celaya Castro-Olega. Divina “Debbie” Accad. The list continues to grow. I wrote their names in cursive and, again, in block letters. I want to commit these names to memory.

I think about their stories. How some of them were so close to retirement. How others emerged from their retirement in order to serve as nurses during this pandemic. How one nurse, Celia Marcos, raced to treat a “code blue” patient wearing only a thin surgical mask, and then died fourteen days later.

I’m moved to read that you have found my book Empire of Care important for the challenging time that we are living in. Learning the history of Filipino nurse migration to the U.S. is relevant now more than ever. This history illuminates that their presence in the U.S. is not new. Their mass migrations to the U.S., especially during times of crises, is six decades old.

Furthermore, to understand why so many Filipino nurses specifically are here, we must go back in time further to when the Philippines was an official U.S. colony. That is when Americanized education, including nursing education modeled after U.S. professional nursing, created the prerequisite training for Filipino nurses and other laborers to work in the U.S. It also fueled Filipino dreams and desires to travel overseas and especially to the United States.

The sizable presence of Filipino nurses in the U.S. and their significant contributions to American health care delivery are the consequences of this long and unequal history.

I also wish to emphasize that this is a history created by the Filipino nurse migrants themselves as well as broader historical forces. I think about all that they have accomplished, beginning with their rigorous training. One of the reasons why I am ambivalent when I hear people say that Filipinos make great nurses because they are so caring is because it erases the hard work of their nursing training and on-the-job experience.

I recall in my oral interviews with Filipino nurses how they had also experienced intense homesickness, unequal work assignments, formidable licensure requirements, and racial and ethnic scapegoating. How they confronted these struggles with bravery and the will to organize so that things would be better for future generations of Filipino nurses has made a profound impression on me. Even in the depths of my grief, their history inspires me.

Being the dynamic and kind educator, curator, and organizer that you are, you are well-positioned to support and care for Filipino American nurses and other health workers on the frontlines. I hope that you participate in documenting their lives as well as their livelihoods through art; that you showcase their stories through curation and collaboration; that you share their contributions with the local and global communities in which we live and serve. I look forward to learning about your future projects.

Wishing you health and safety,

Cathy

Footnotes:

1) Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History, Duke University Press

2)“Similar to Times of War”: The Staggering Toll of COVID-19 on Filipino Health Care Workers: https://www.propublica.org/article/similar-to-times-of-war-the-staggering-toll-of-covid-19-on-filipino-health-care-workers

3) On Pandemic’s Front Lines, Nurses From Half a World Away https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/20/world/asia/coronavirus-philippines-nurses.html

4) The Fragility of the Global Nurse Supply Chain https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/04/immigrant-nurse-health-care-coronavirus-pandemic/610873/

5) Filipino front-line workers pay ultimate price in UK https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/coronavirus-filipino-front-line-workers-pay-ultimate-price-uk-200501075917665.html