Reports from the Field are perspectives from curators from around the world, who are alumni of the Curatorial Intensive, ICI's professional development program for emerging curators. The commissioned texts are reflections on the impact of the global pandemic on their lives, ways of working, their communities, and how they are adapting as a response.

Luis Carlos Manjarrés Martínez, Alumnus of the Curatorial Intensive New Orleans '19, writes from Bogotá, Colombia. To read and download the PDF version, click here.

Inequality in Bogotá is seen from my window. Photo: Daniel Sarmiento.

In Spanish, curar <to cure> means both to heal and to curate. With the current conditions in the midst of the pandemic, the polysemic characteristic of this word seems more relevant than ever. While we readapt to the new realities of an emerging society, I want to share some of my thoughts about exhibitions as a measure of psychosocial care; a methodology that might help us guide our work in the current context and to envision a future perspective of curatorial practices.

We are living through atypical times where uncertainty opens up the possibility of envisioning a shift of paradigm in art, culture, and museums. However, such a short time has passed since it all began, that we have not been able to identify the new order and the demands that will fall upon curators, educators, and other cultural workers. Nevertheless, it is important to prepare ourselves by proposing alternative ways, paths, or places to convene with others, and instill trust towards each others’ bodies, even those we share similarities with, as well as to persist in the inclusion and accessibility of otherness in cultural institutions.

While we are in this mandatory break, we should evaluate the social role of cultural institutions, identify what has been done by them (or us) until now, and from there prioritize our efforts to carry out pertinent, useful, reparative, and healing curatorial statements. Curatorship at the service of vulnerable people and communities is necessary now more than ever before to change the cycle of historical subordinations which have become more evident during the pandemic.

Currently, a good number of texts and papers about museums in times of COVID-19 are circulating. They address issues related to sustainability, how to slow down, rethink presentiality and prosociality, the end of the object’s fetishism, the urgency to turn to virtuality, and even about the precautions that will have to be taken to reopen the museums. But few have questioned the responsibility museums and curators have in perpetuating (or not) discriminatory discourses and the status quo of a selfish, individualistic, and deeply unequal model. Cultural institutions are not exempt from participating in discussions about the co-responsibility of the negative impacts of the pandemic and, based on a critical point of view, should commit to becoming agents for change.

Desoloate street in the center of Bogotá a few blocks from Luis's home. Photo: Luis Carlos Manjarrés Martínez.

We should not allow “health and sanitation” to be established as a category for exclusion in our daily lives and, in extension, in museums, we must certainly avoid for them to become more aseptic (literally and metaphorically) than they already were before the lockdown. We should make the best out of this situation, use it to innovate and create museological processes that might help to heal the psychological effects caused by COVID-19. But let’s not limit this possibility to the subject matter of the pandemic, and broaden it out to remedy and repair collective suffering and traumas, caused by discrimination and segregation due to sex, gender, age, race, social class, country of origin, religion, physical or emotional disability, to name a few. If we can demonstrate the effectiveness of the museum and exhibitions in the treatment of collective trauma, we will be relevant and necessary for society in post-pandemic times.

To do so, first, we have to be aware of the healing potential that museums have when they carry out processes based on a social sense and an ethical commitment. We should take the time to think over the implications of each curatorial decision since displaying the past without asking what memories are being denied or suppressed is negligence, an unacceptable waste in a time of economic austerity and ethical failure.

It is therefore vital to recognize the cultural sector as a professional field under the care of the collective and the social weave. We must understand that the exercise of curatorship consists of recomposing, mending, healing, taking care of emotions and affections; understanding responsibility in the management of memory, and oral history is our most valuable heritage. Seeing that the museum is what makes meetings possible, in a society of uncertainty and over-information, everything that unites us must be empowered and communicated.

We must also be aware of the multiple and diverse challenges that the current situation demands of the cultural sector, moving away from the logic of the market and approaching the socio-psychological needs of people. As healers, we must accept that our true responsibility focuses on the ability to put symbolism at the service of the common and the collaborative.

It is important that we consider museums and cultural institutions as receptive spaces that link curatorial work to the concept of communication as a social activity. This helps to build relationships of trust and collaboration, to foster conversations that allow us to commemorate together, and to reflect on the past.

Some of us are already undertaking museological processes focused on topics related to the current pandemic. It is up to us that these exhibitions do not replicate what is often hastily constructed, with official statements, conclusive or heroic narratives. The ethical duty is to remember that we are working with the pain of those who could not say goodbye to their loved ones, with the trauma of those who lost everything and to become aware of our own emotions. In my opinion, activists should be leading the conversation on this topic, giving voice to people and communities that have been most dramatically affected by COVID-19, denouncing and making visible what is currently buried in the emergency and in the urgency of saving both lives and the economic system.

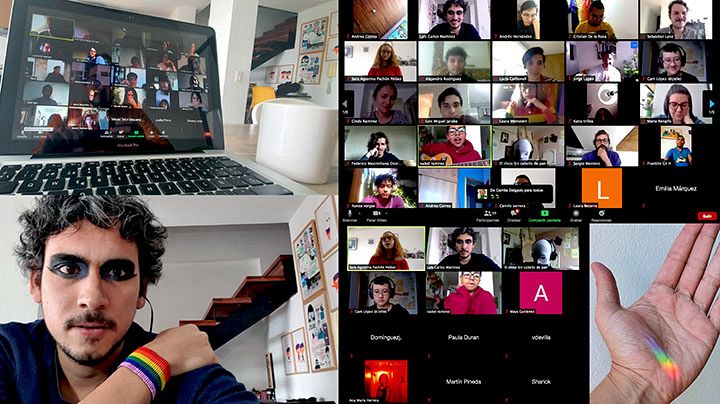

With the MuseoQ, we commemorate the International LGBTIQ+ Pride day from home. My rights are not quarantined.

I would like to conclude with some ideas to keep in mind when we embark in curatorial activism projects in the future:

Delimit a territorial and populational approach to address the issue.

Research a list of actors and invite them to participate.

Create public and accessible spaces for participation.

Once the community has gathered, collectively define the purpose of the exhibition or museology process.

Be clear about the intention of the exhibition or the museology process.

Be informed as to why these people are interested in contributing to the exhibition. Many of them require a place to process their mourning and to participate is, for them, cathartic and liberating.

Invite and involve colleagues from all areas of the cultural institution in the process: participation starts at home.

Be honest, build trust, and create networks of affection among the communities and hereafter, co-curators.

Be aware that in the course of the collaborative process and exhibition, new needs and demands may arise for the communities and co-curator.

Give up power and control, lose the fear of criticism, leave your ego, and the urge for authorship behind.

Do not let any institutional interest prevail over the interests and needs of the people who are part of the exhibition process.

Be aware that:

The exhibition is a process.

The exhibition is a means, not an end.

The exhibition is not the most important thing.

The complaints that the exhibition does not make, the silences, include and integrate participation devices for the memories that arise.

Curatorship is a political action.

Curatorship must be a social practice.

The exhibition is made by someone, made for someone, and worked among communities. Nothing about us without us.

These are lessons to be learned about the museological processes in parallel to other social emergencies living in Latin America, such as war, xenophobia, and LGBTIphobia, threats that worsen with COVID-19, and I hope these are taken as an invitation to continue fighting for rights as they are not granted and must be taken. Now, it is time to embrace our diversity and support each other in our work.