Community

It’s important to remember that our cultural institutions are made of people, and successful resistance is dependent on community care and trust. Community care in the art world is a form of curatorial activism in its own right, which can be as simple as coming together to engage openly and meaningfully. Art is meant to build community, to inspire people, and to allow access to the stories that make up the collective. Through art and study as acts of resistance, we can learn from the many ways people have already challenged institutions.

To learn how these values are operating in non-traditional institutions, I spoke with saylem m. celeste and Triniti Watson of Midnight Care Collective about their goals and the relationship between community and art. saylem m. celeste is a Detroit-born Care Practitioner who uses art, conversation, and sound for collective liberation and healing, and was a 2022–23 Artist in Residence at Detroit Justice Center, where they met Triniti Watson, a writer and community facilitator based in Michigan. celeste founded Midnight Care Collective (MCC) as a Detroit-based Black feminist and transformative justice group dedicated to supporting communal well-being through creative methods. For MCC, community care is not solely an aspect of art, but an essential element that fosters collaboration and shared experiences. The collective emphasizes that care and art should not be transactional, but an intrinsic part of life and a direct means of building connection and making clear commitments to each other.

Midnight Care Collective, left: Triniti Watson, right: saylem m. celeste

Since February of 2023, MCC has held a series of community activations centered around the intuitive resilience of Detroiters and examining the role communal care plays in our collective resistance. These efforts emphasize social justice movement work, communal relationships, and healing beyond limiting ways of being, as well as meaningfully moving beyond traditional institutional spaces. celeste's experiences in environmental science, combined with their disillusionment with traditional art institutions, especially during the crises of 2020, motivated them to seek a more community-centered approach to art. Here, I see my own experiences reflected. From 2017 to 2020, I worked as a farmhand at an urban commercial farm. I left my position only because of the intense emotions I felt during the George Floyd protests while working on white-owned land. Participating in the protests and witnessing how little the institutions in majority-Black cities spoke up was disturbing beyond words.

The challenges that I, like many other employees of traditional museum institutions, faced were reflected in a lack of institutional support for local artists and staff, the absence of supportive (or non-existent) HR departments, and a culture that prioritizes capitalism over collaboration. celeste believes that building a trustworthy community requires a commitment to transformation, patience, and truly seeing and supporting each other. They have faced challenges related to navigating the politics of art spaces, where the focus is often on individual success rather than collective growth and support. "Institutions are not neutral; they are often tied to power dynamics and can perpetuate white supremacist culture," celeste remarks. “It's essential to recognize this and seek alternatives that prioritize community and mutual support.” Midnight Care Collective has found solidarity in projects such as the Free Black Women's Library in New York and the Black School in New Orleans. The pedagogy and practices of these organizations focus on community and shared values rather than just the outputs. Art institutions, celeste suggests, could learn from these models and shift their practices to actively dismantle oppressive structures while prioritizing inclusivity and genuinely engaging with the communities they serve.

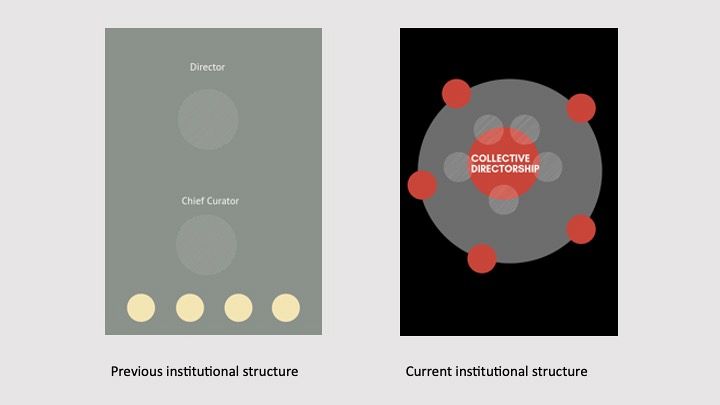

Resisting institutional power requires not just reimagining how cultural spaces can operate, but taking action behind theory. Traditional museum hierarchies uphold values that exclude, rather than empower, discourage accountability, and isolate individuals rather than encourage collective progress. Yet, curatorial activism and the commons offer alternative models that center community care, trust, and shared abundance. Cultural organizations are made up of people, and their success depends on prioritizing those who sustain them. These relationships form the foundation of vibrant and responsive art communities. More than an object or an institution, art is a social language, a tool for building community, and a means of collective storytelling. By engaging in the arts and using research as acts of resistance, we can meaningfully imagine new possibilities for the future of creative workers.