Leah Gordon and Andre Eugene, recipients of the 2015 CPPC Travel Award, present a travelogue of their research in the Dominican Republic in September 2015 (Part 2 of 2. Read Part 1 here).

Dominican photographer, performance artist and filmmaker Polibio Diaz came over to the hotel to meet with us. We started discussing Dominican and Haitian relationships. Polibio explained that he was born in the border region of Barahona and he said “the frontier society is very permeated.” He expressed that society there on the border is less racist and nationalistic; he believed that his social sensitivity was learned at home. He spoke about a collaboration between a group of Haitian and Dominican scholars, writers, and artists called Borders of Light, which came together to reflect upon the 1937 massacre of Haitian sugar cane workers by the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo that killed up to 12,000 migrant workers.

This is held on the border on the shores of the River Massacre, which had gained its name due to an earlier colonial struggle, where a majority of the bodies were dumped. Polibio also did a performance on December 18th to commemorate International Immigrants Day. We all reflected on the idea of having Hispaniola as the theme for the next Ghetto Biennale. Hopefully, through the contacts we have made, the next biennale would really bring together Dominican, Haitian, and international artists to reflect upon the history of the shared island and the proximity and distance. Polibio spoke about that lack of infrastructure for Dominican photographers. He feels that the aesthetic photographic canon is limited and feels like he belongs to a current of decolonized artists. Polibio is the one of the few artists that we met in the DR who has done a considerable body of work in Haiti. He also told us how the Davidoff grant for a residency in New York really helped stretch and challenge his practice, and it was invaluable for him as an artist.

With Polibio Diaz.

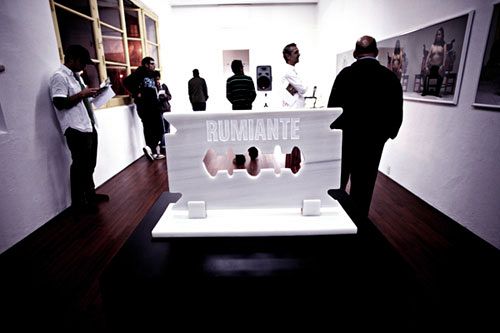

We walked to see the Bienal Nacional de Artes Visuales at the Museo de Arte Moderna. We were pleased to have the chance to see the work of Tony Capellan, who was once a member of the influential artist group, Quintapata. Tony left the group and is also quite difficult to reach, as he has no email. We managed to contact him a few times by phone but sadly never met him. His work has been honoured by the Bienal and it gave us a chance to see how important his work is within the Dominican canon. Eugene and I already knew his work from the Kreyol Factory exhibition in Paris. We also saw some of Limber Vilorio’s work in the show.

Bienal Nacional De Artes Visuales.

Tony Capellan's work, Bienal Nacional De Artes Visuales.

Limber Vilorio's work, Bienal Nacional De Artes Visuales.

Bienal Nacional De Artes Visuales.

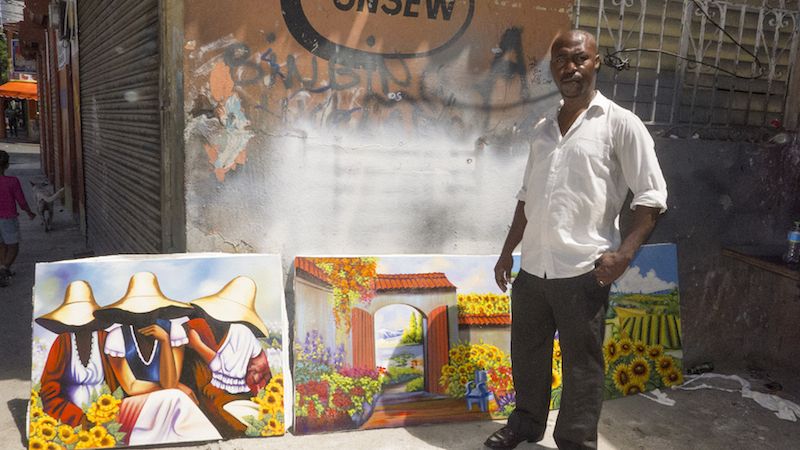

In the afternoon we met with some Haitian artists in Santo Domingo − Phederbe Thegenus, Marc Achil Lazarre & Alfred Jean Michel − who produce both their own work and work for the tourist market. The overall message was that of frustration; similar to the Haitian artists in La Higuey, they felt frustrated in their own personal ambitions as painters and had to supplement their earnings with tourist paintings.

Phederbe left Haiti 30 years ago mainly because he felt he could train to be an artist in the DR. He knew someone who would be his teacher, whereas he felt that he had no future to train in Haiti. Phederbe stated that 15 years ago it was a good life painting and selling work to the tourists but the marketing strategy has changed now. He blames packaged tours, meaning that the visitors have less money in their pockets when they look around the streets, and the hotels and resorts control what they buy and where they buy it, so now Phederbe is finding life a lot more difficult. He has his own aesthetic that he showed us: very complex and richly detailed pictures of birds and vegetation, but he sells these paintings to clients in New York which have Haitian art galleries in Brooklyn. He says that he hasn’t sold work in the DR for over seven years, and the only works sold in town are copyist and derivative. Phederbe said though he can support his whole family from sales in NYC and Spain and he can sell a painting similar to the one in the photograph for $100.

He and Marc Achil Lazarre also talked about how difficult they find it to have any online presence. While Phederbe has a Facebook page, they both felt that a website would be out of their reach. Marc has lived in Santo Domingo for eleven years and has been painting for twenty years. He is also finding it increasingly difficult to sell in the DR, although he does still sell some paintings for about $50 and sells to NYC as well. Both of them complained that the tourist aesthetic is forced upon them. When I asked for their ideal forms and themes, Phederbe said that he prefers birds and Marc Achil would prefer abstract to figurative.

Artist Phederbe Thegenus.

Artist Marc Achil Lazarre.

We finally met with Alfred Jean Michel who had an earlier career working on naïve paintings, which were sold at some major galleries in Haiti before he came to the DR. He prefers to make paintings of peasants working in the mountain forests and fishermen; whilst he likes to paint Vodou scenes, he cannot sell them in the DR. Alfred also confirmed that the economy no longer really supported painters in Santo Domingo, due to the change in tourism practices, mainly the packaged holiday tours.

Artist Alfred Jean Michel.

In the evening we met with Alanna Lockward, who had produced a document called Dual Wounds for the hemispheric institute, which she describes as a “conceptualization of the lineage of counter-hegemonic narratives on Haitian-Dominican relations.” In Alanna’s words, this multimedia was “conceived as a space for love and reconciliation between two Caribbean populations that share the inexorable continuities of coloniality.” It features the artworks of Haitian and Dominican artists from Hispaniola and its diaspora.

Later we went to find the mural project, started as a project called the Bienal Marginal (Marginal Biennial) that took place in 1992 in a ‘popular neighbourhood’ called Santa Barbara. This project was instigated by Silvano Lora, who is a painter, sculptor and cultural organizer. He has been considered an icon of national Dominican art and also is associated with social struggles in the cultural history of the late twentieth century. Lora wanted to promote popular art, alternative cultural spaces, and cultural exchange with marginalized groups. In the Marginal Biennial, works by both renowned artists and unknown folk artists were exhibited. Eugene and I were quite interested as it promised many parallels with the Ghetto Biennale. We took directions and finally found an area, which had many indicators of poverty, with many murals on the surrounding walls. We were politely informed that it might be advantageous to leave the area, especially because I had a small camera.

Santa Barbara.

We met with Stephen Fisher, British Ambassador to the DR and Haiti, who helped contextualize and explain from an establishment position, the situation between the DR and the Haitian migrants. Stephen said that twenty months ago the Dominican government realized that had an unusually large number of Haitian migrants were in the country but also realized that most of these people were important to the economy. Therefore, a decision was made to regularize the status of the majority of these immigrants and to give them a legal right to reside in the Dominican Republic. They proceeded with a process of regularization, and any immigrant was invited to go to a government office with ID so that their status would be regularized.

When the process closed on August 17, 2015, it is estimated that 288,000 people had registered for the chance of being regularized. Stephen said though not all of them had received their residence permits yet but he thinks this will go forward. He believes that this is a positive move for Haitian migrants; if they have the right to be in the DR legally then they will have better rights in the workplace too. Stephen says whilst many people have seen this as a plan to exclude Haitians from Dominican territory, he sees it the opposite way as a plan that allows people to stay with greater rights and protection. He mentioned that not all individuals who applied were accepted and that they, along with the migrants who failed to apply, after August 17th were vulnerable to deportation, since the Dominican government had ended its self-imposed freeze on deportation.

Stephen acknowledged that there have been some deportations since the August deadline. He felt that the programme, which has been monitored by the UN and international migration organizations, has respected people’s rights and acted in a civilized and legal way. He acknowledged that historical issues relating to the treatment of Haitian migrants in the DR may have colored the expectations of the Dominican government’s handling of this situation - though in his opinion, he thought that the Dominican government was respecting the rule of law. We also spoke about the irony that whilst there were demonstrations in Trinidad about the Dominican treatment of Haitians that Andre Eugene almost didn’t receive a visa to visit Trinidad, even though Haiti is a member of Caricom.

In the afternoon we went to visit Jacinto Pichardo Vicioso to talk about the Bienal Marginal. He is a Professor of Architecture at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, the oldest university in the Americas. He worked closely with Silvano Lora, the main creator on the Bienal Maginal. This was one of the most important meetings and interviews as we could recognize the many parallels between the ethos of the Bienal Marginal and the Ghetto Biennale.

Jacinto Lora.

Jacinto told us how in the period between the end of the Trujillo dictatorship and the US invasion 1961-1965, Lora had been a member of the Popular Socialist party and then after 1965 a member of the Dominican communist party. There were a number of artists and poets coming together to unite against the US invasion and using art to express their opposition to the US in the DR. Jacinto said to describe Silvano Lora: “He was always using the paintbrush as a weapon.”

Lora decided to hold the Marginal Bienal in 1992 as part of a global anti-colonial political and critical response to the commemoration of the 500-year anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas. He held the Bienal Marginal in an area called Santa Barbara, an informal neighbor (where we had visited the night before) on the northeast edge of the colonial district. The area, which is on the banks of the Ozama River, was originally where the slaves were sold. By the early 1990s, it was a difficult neighborhood with issues around drugs, prostitution, and gangs, but Jacinto says that the situation and conditions are much better now. He said that many people in the neighborhood were employed as security and now work full-time as security for the many film crews working the Colonial district (we saw crews working there every day during our stay).

Jacinto didn’t have much more concrete information about the Bienal Marginal but said there was information on the UNESCO website as well as a number of books. He advised us to visit the Museo Colonial, which was started by the Silvano Lora Foundation. Eugene and I were both very excited and interested to discover more and can imagine returning to the DR to conduct some focused research on the history and politics of the Bienal Marginal.

Bienal Marginal.

After this meeting, we rushed back to the Colonial District for a chance to visit the Museo Colonial. We were happy to find an old catalogue in Spanish, which (once translated) will be the basis of my further research. I see that there is a list of the people and types of work which were invited to participate including: professional artists (with a preference to those working with recycled materials), installation and performance artists, artists who are not traditionally trained, artists working outside of the gallery and museum system, collectives, poets, musicians and writers, popular and primitive painters, and creators of altars and popular religious and magical objects. This definitely has parallels with the demographic of the Ghetto Biennale. We also visited the nearby Centro Cultural de Espania and saw the Miro exhibition. This centre was a lovely space that is well-funded (a Miro show proves this) and has a really extensive public programme too.

Museo Colonial.

Centro Espania.

In the evening we met with Raquel Paiewonsky, another member of Quintapata. She was explaining that part of the foundation of Quintapata was to find a new form of organization, as sourcing much government funding involved too much bureaucracy. Raquel said that their show at the Centro Cultural de Espania was crucial in their development. When we asked if it was easy to get curators to see her work in the DR she acknowledged that a number of exhibitions − Global Caribbean (curated by Edouard Duval-Carrie), Infinite Islands (curated by Tumelo Mosaka for the Brooklyn Museum), Kreyol Factory (curated by Yolande Bacot for Par de la Vilette, Paris) and Caribbean Crossroads (curated by Elvis Fuentes for El Museo del Barrio, New York) − has really opened up the territory and increased visibility.

She said that the Caribbean is like a mini world as every island is so different. Raquel is another artist who has come through the education channel of the Davidoff Initiative, Altos de Chavon art school, and then finished her education at Parsons in New York. We were aware what a huge difference an education project like this could have on the creative life of Haiti. Raquel had just returned after receiving a Davidoff grant for a 3-month residency in Berlin, which gave her a studio and the opportunity to network with curators and other artists and to experience so much cultural activity in Berlin. Raquel feels that the Davidoff Initiative has been instrumental, through its education and residency programme, in enlivening the cultural life of the DR. She also mentioned a new online magazine called Artes as occupying an important role in the Dominican art scene too.

Later we met with Jorge Gonzalez, who is doing a new mural project in Santa Barbara. There was a sense that this new project is more projected onto the neighborhood and has a far less radical engagement with the local residents and radical arts practices. It appeared to be more superficial and tourism friendly.

The same evening we met with aid consultant Helen, who worked in Haiti before working in the DR. Firstly she stated it was important not to confuse the programme that was put in place for people born in the DR that enabled them to register for legal status with the decreed programme to regularize migrant workers in the DR. She wanted to stress they are two distinct things, which are confused by many of the news reports.

Helen then spoke about the registration of the migrant workers, which she said is considered to be a success due to the number of people (288,000) that have come forward to enroll. She said that if this was all true, at the end of this, these people would be formalized and therefore would have rights to social security support. But she is still circumspect, as all most of these people have at the moment is a document to prove that they have registered. She explained that the criteria was really tough and they had to show rental contracts, phone contracts, and bank accounts, which most people in the informal sector would not have. Each person registering had to get seven neighbors to testify on their behalf and this had to be notarized, which involved a cost.

Consequently, Helen said when one considers the amount of documents each person has to provide, she would be surprised if there were a lot of people able to meet the full criteria. She stated that at this point very few permits have been delivered and only registration receipts have been provided. The registration receipt allows them to stay two years if they have a passport (one year without a passport), but it does not allow them to work legally. If any of these people are caught working just holding a receipt, they can be deported, and she questions what would happen at the end of the year. She is unsure what is going to happen in the long term and feels that the people who have registered will be on the system and living with a bit of an axe over their heads.

MIAMI

We left for Miami and met with Edouard Duval-Carrie, curator of Global Caribbean and renowned Haitian artist. He discussed what is considered the peculiarity of Haiti, and how curators have played on this sometimes not completely considering the negative as well as the positive of this strategy. He believes that this ‘peculiarity’ was a benefit to Haitian art but also a curse. When discussing art from the lower classes in Haiti, he questioned how do artists in the contemporary world present themselves if they are strictly visual but not articulate? He said the discourse is there but it is implied, not stated. He felt that in the contemporary moment it is difficult to arrive just with visuals and not be able to articulate a contextualization of the work. He said that his project Global Caribbean was conceived to help Haitian artists know that there is a discourse surrounding their work and that their engagement should be with this dialogue as well as the visual aspects of the work. He is critical that some artists are still dependent on the revelation that happened two centuries ago and wants to pose the question: What are you saying now?

Edouard Duval-Carrie.

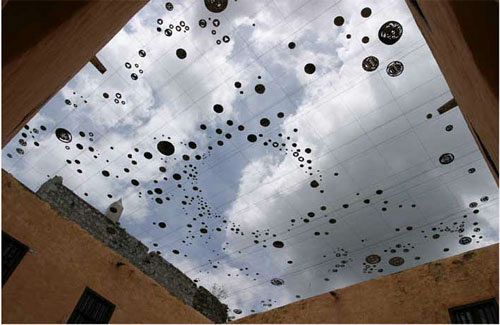

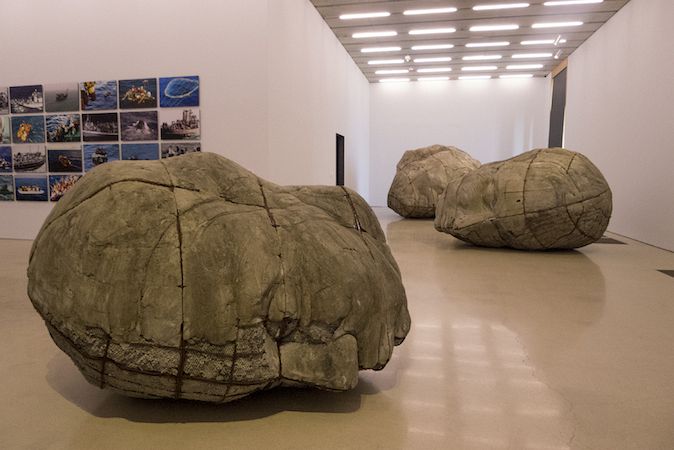

Eugene left in the morning and I took the chance to visit the show at Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) called Poetics of Relation, which was inspired by the writings of author and philosopher Édouard Glissant and used his “logic of displacing the singularity of nationality, language and ethnicity, in exchange for adopting multiple rooted identities” as a way of exploring diasporic communities in Miami. It was such an important show to see at the very end of this trip and I was especially pleased to see another piece by the elusive (in person) Tony Capellan.

Installation views, Pérez Art Museum Miami.

The research for this project was made possible by the generous support of ICI and Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (CPPC) through the CPPC Travel Award for Central America and the Caribbean.