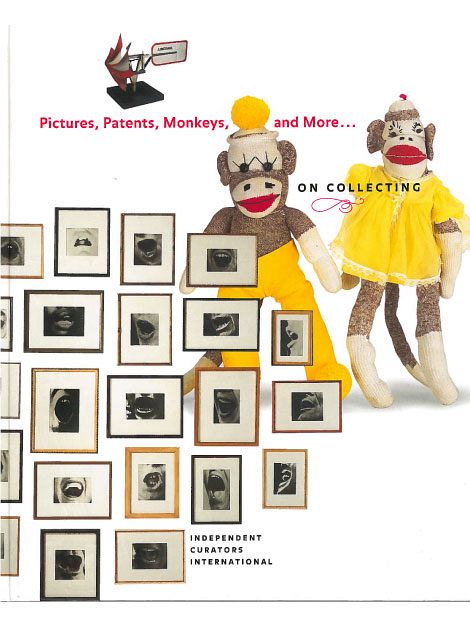

Contemporary life can seem unmanageable – except to the collector who has it within his or her grasp to acquire the complete set of any one thing, to become the master of a chosen domain. This groundbreaking exhibition, Pictures, Patents, Monkeys, and More..., examines the collecting impulse in different manifestations, and – as it raises important questions about the nature of art and its profound and eternal appeal to us – presents outstanding examples of contemporary American art.

In the realm of collecting, everything is fair game: comic books, rare porcelains, bottle caps, Old Master drawings, butterflies, antique dolls, and contemporary art. Pictures, Patents, Monkeys, and More... offers a representative selection of objects from three different kinds of collections: contemporary fine art (from Robert J. Shiffler Foundation in Ohio); artifacts of popular culture (from a private collection of “sock monkey” toys): and the public record (patent models from the U.S. Patent Office, now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution).

Ohio businessman Robert J. Shiffler has been collecting artworks since 1986. In 1998, he established The Robert J. Shiffler Foundation to promote avant-garde culture in its most challenging manifestations, through tours of the collection, special events, educational programs, exhibitions in its Greenville, Ohio, storefront, and an unusually generous loan policy. The art collection now totals over 600 works, with a companion collection consisting of an important archive of artists' books, multiples, performance documents, videos, computer-based works, and audio recordings.

The National Museum of American History, one of many divisions of the Smithsonian institution, holds nearly 10,000 patent models, the largest and most comprehensive such collection in the world. In one of its first acts of government, the U.S. Congress instituted a patent system that deviated from the English system in one crucial aspect: along with the customary written description, applicants had to submit a three-dimensional model. In the 1920s, the federal government decided to disband the U.S. Patent Office's collection of models and offered the Smithsonian Institution its pick of the lot. The objects date from 1836 to 1880, and from the 150,000 available objects, the Smithsonian chose about 10,000.

Sock monkey toys have been a popular handicraft of the American Midwest since 1953. Considering what a humble homemade today it is, the original sock monkey seems to speak less to the children of post-war prosperity than to the nostalgia of the parents who grew up during the Depression. The private collector who owns the collection belongs to neither group, but to the generation of the 1960s, many of whom do not even know what a sock monkey is. In 1985, he launched the collection to demonstrate the historic existence and downright ubiquity of these toys. The collection numbers almost 2,000 objects, all recorded in a log book with specific codes for common features of each toy.

In exploring these three different collections, the exhibition’s aims are twofold. Firstly, it investigates the collecting impulse. Why do so many of us accumulate objects? How is institutional collecting different from individual passion? As a cultural expression, is collecting about fame and fortune, or anxiety and mortality? Secondly, it encourages an understanding of contemporary art by presenting it in the context of collecting. What distinguishes an object as art? How does its creation and collection differ in value, interest, and purpose from other pursuits?