This is the second journal entry for a series of research trips by María Elena Ortiz, the 2014 recipient of the CPPC Travel Award. She will visit new and established contemporary art centers, artist initiatives, and film festivals in the Caribbean countries of Aruba, the Bahamas, Martinique, and Trinidad and Tobago. Her research will explore film and video practices, through interviews with local cultural producers and artists, with the aim of strengthening the ties between art in the Caribbean and the Diaspora in the local community of Miami.

Although the distance between Martinique and Miami is comparable to the one between Miami and New York City, traveling to Fort-de-France involved three planes and a mini tour through the most notable airports of the French Caribbean. Before arriving in the capital of Martinique, I had layovers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, typical layovers when taking planes to some of the Lesser Antilles. Once in Fort-de-France, I met with internationally recognized artists, such as Ernest Breleur, whose work engages with contemporary theories on creolization and fragmentation, while aesthetically alluding to the modern traditions established by figures such as Wifredo Lam. I also came across a younger generation of artists interested in experimental and conceptual approaches, such as Henri Tauliaut, whose robotics and installations question gender roles in personal relationships. At the same time, it seemed that institutionally speaking the most fascinating cultural processes are occurring at newly established commercial galleries and old sugar plantations, or rum distilleries, repurposed into exhibitions spaces for contemporary art.

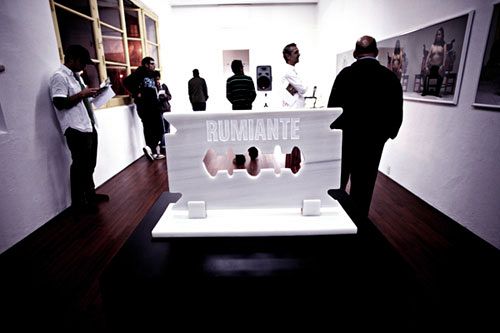

Exhibition view of Réflexions (about the notion of progress) at 14°N 61°W Espace d’Art Contemporain, July 2014.

In Fort-de-France, there is only one commercial gallery dedicated to contemporary art, 14°N 61°W Espace d’Art Contemporain, founded by Caryl Ivrisse. This platform generates exhibitions and publications concerning the dynamics of the Caribbean on the global stage. There, I saw the exhibition, Réflexions (about the notion of progress), in which a group of local and regional artists produced works inspired by the question: what is progress in Caribbean environments? Among the responses, David Gumbs, a media artist born in St. Martin and based in Fort-de-France, produced an installation involving sensors that composed digital images on a screen when activated by people’s movement. This work generated a playful situation that points to the relationship between technology and progress. Other works questioned war technologies used in the Caribbean, such as Raymond Médélice’s strikingly expressive paintings of drones. The region has been used as a test site for military weapons, from testing Agent Orange in the tropical forests of Puerto Rico in the 1960s to Predator drones in the waters of the Bahamas in 2013. In this sense, Réflexions (about the notion of progress) presented contrasting views embodying the challenges of “progress” in Caribbean environments.

View of artist Ernest Breleur’s house, July 2014.

View of old rum distillery, July 2014.

View of exhibition space presenting works by Jean Luc de Laguarigue, July 2014.

I had the chance to meet art critic, Dominique Brebion, Advisor to the Regional Cultural Affairs Board of Martinique, and Suzanne Lampla, who also writes about art. Brebion has been a key figure in governmental affairs and consolidated a mature generation of artists including Ernest Breleur and Jean-Luc de Laguarigue. Together, we visited the studio of Breleur, who is an avid collector of Caribbean art. Walking into his studio, I was captivated by his approach towards painting, sculpture, and installations, which address aesthetic connections among Martinique, Africa, and Europe. We then visited an exhibition of photographer Jean Luc de Laguarigue in an old plantation building. He grew up in a plantation family, but turned a space of their old family distillery into galleries. When taking photographs, he seeks inspiration from the theories of Édouard Glissant. He reinterprets the sites of plantation life, as he captures the social portraits and architectural landscapes of the region. After this studio visit, Lampla took me to meet Shirley Rufin, a young artist working in photography and new media interested in issues of representation on the island. Like the American South, Martinique’s plantation history shaped social hierarchies, and on this island, artists from different generations and backgrounds question that legacy.

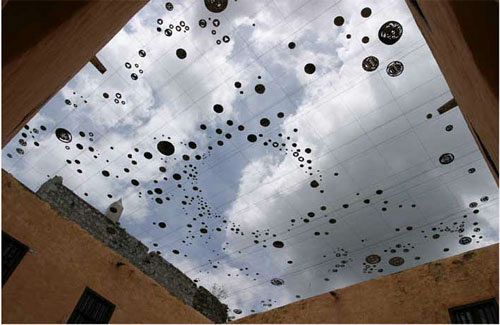

View of Fondation Clément, July 2014.

The most noteworthy art center in Martnique is Fondation Clement, an old rum distillery turned into an art center. Located in a beautiful mountainous location, Fondation Clement has a sculpture park, an exhibition space and collection. They produce exhibitions and publications focused on Martinique, as well as from other countries in the region. There, I saw the exhibition Insomie, showcasing the photography of Phillipe Virapin, whose images showed nocturnal scenes of his native Guadeloupe. These landscapes reminded me of the streets and cemeteries of New Orleans. Fondation Clement also showcases traveling exhibitions originated by foreign institutions.

View of exhibition Insomie at Fondation Clément, July 2014.

View of sculpture park at Fondation Clément, July 2014.

On the island, several artists and cultural practitioners divide their time between Fort-de-France and Paris. In Fort-de-France, I had studio visits with David Gumbs and Henri Tauliaut (whose works are described above), as well as with Hervé Beuze, Audry Liseron-Monfils, and Bruno “Iwa” Pédurand. Their works varied greatly in terms of approaches and themes. Beuze, for instance, is internationally known for combining local raw materials to create sculptures and installations centered on ideas of memory and identity in Martinique, specifically the reinterpretation of the island’s map. Born in French Guyana and now based in Fort-de-France, Liseron-Monfils works in drawing and performance to examine the physical and symbolic borders. Pédurand has been working for over ten years on the dynamics of post-colonial societies in the West Indies. These artists also work in the local art school, and they taught me the word Béké, a term denoting the minority of white creole families who control most of the industry on the island and support cultural initiatives.

View of Théâtre Aimé Césaire, July 2014.

View of statue of Josephine beheaded, July 2014.

Lastly, I did site visits to the Théâtre Aimé Césaire and the guillotined statute of Empress Joséphine, Napoleon´s wife, who grew up on Martinique and belonged to well-known plantation family. In 1991, a group of people painted red drips on her neck and beheaded the Empress in typical French fashion—a social performance illustrating current local debates about race and power. Moreover, the streets of Fort-de-France are breathtaking, as one can appreciate Martinique’s unique creole language, distinct colonial architecture, and the city’s connections to other regions of Africa colonized by the French, such as Senegal. In Fort-de-France, it is easy to find Senegalese food and fabrics, artists engaging with the island’s history, and private and public initiatives that generate discourses on contemporary art.

View of streets of Fort-de-France, Martinique, July 2014.

The research for this project was made possible by the generous support of ICI and Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (CPPC) through the CPPC Travel Award for Central America and the Caribbean.