Pablo José Ramírez, the sixth recipient of the ICI/CPPC Travel Award for Central America and the Caribbean in 2019, reflects on his travels to Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Honduras, Belize, and Guatemala to learn about the history and culture of Garifuna people, the descendants of an Afro-indigenous population from Saint Vincent.

Click here to listen to audio from Pablo José Ramírez's event at ICI New York

History of the Garifuna:

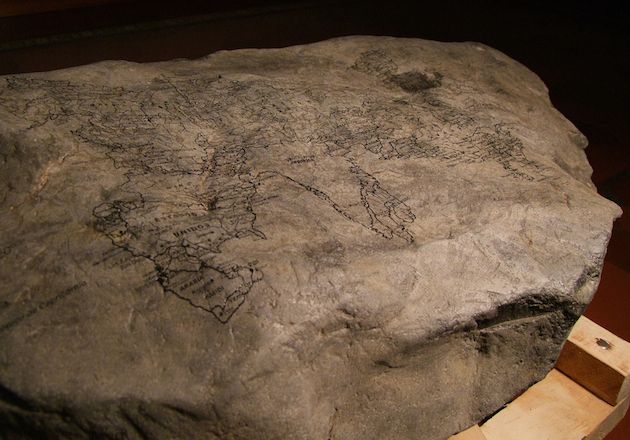

According to the most extensive and official accounts of Garifuna history in 1635, a ship from what we know now as Nigeria, sunk in the Atlantic Ocean. Inside the ship, a group of enslaved people were being taken to the Caribbean to work on plantations. Many of these enslaved people escaped during the wreck, reaching the coasts of St. Vincent and the Grenadines where they were received by indigenous Arawak communities, who initially subjugated them before becoming allies and giving birth to the Garifuna people. The Garinagu people represent one of the most paradigmatic cases of Afro-Indigenous colonial mestizaje. Their history is crossed by two colonial settlers (the French and British colonies) and by the encounter of two continents, giving birth to a vibrant culture, which holds onto its entrails, the scars, and the codes of resistance that after more than three centuries remain alive within the mythical never-enslaved Garinagu.

When the British colonizers arrived on the island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, the Garinagu maintained a tense alliance with the French. After fighting the British for more than a century, the Garinagu were forced to surrender and the French were kicked out of the islands of the Lesser Antilles. The Garinagu were separated in terms of their phenotype: the ones with more “indigenous features” were allowed to stay, while the ones with “black features” were forced to leave the islands in a violent act of exile, pushed to the open sea with little chance of survival.

At the open sea almost half of the Garinagu who departed passed away. The rest reached the coast of Honduras, near what is now known as La Ceiba, where they were received by the Spanish colonizers. They were allowed to stay under conditions of exploitation, mostly on banana plantations. After some time, they were allowed to settle in the islands of Roatan and from there they would also move to Belize and Livingston. They have always been in movement, more recently migrating to the US.

Two of the bigger settlements of the Garifuna are on the island of Roatan in Honduras and in New York, the latter due to the massive migratory movements in the early 20th century from Central America to the United States. This not only threatens the preservation of Garifuna culture, but depicts an accelerated transformation within their communities. The Garinagu population is indeed accustomed to movement and has somehow made deterritorialization a place to affirm and to build collective agency and strength, however we are still witnessing what this new moment of migration will bring.

Part 1:

Image: Garifuna Flag.

I have always been attracted to the relationships that artists establish with environments outside of urban modernity. These relationships are indispensable markers for thinking of contemporary practices in Latin America. In these territories artistic creation occurs beyond neoliberal cosmopolitanism. It is for this reason that much of my research work focuses on these parts of the world. This project has led me to travel to two radically different worlds, within the borders of the same country, Tegucigalpa and the Honduran Caribbean coast, as the first stage of my research. One of these places was the strange island of Roatán, where the voracious tourist infrastructure exists in contrast with the community of Punta Gorda. This is currently the only Garífuna community on the island, where they were taken by the British in the second half of the 19th century, after almost 100 years of the anti-colonial resistance in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

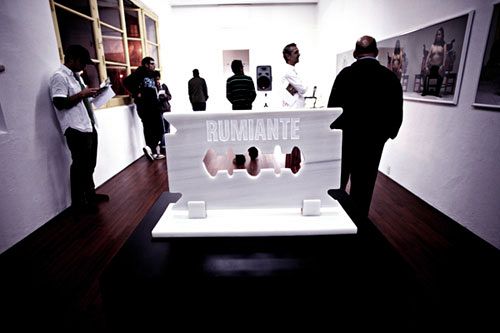

“The history that they have told you is incorrect”, was how Jorge Chavez – a Garífuna musician and performer - introduced himself to me the day we first met in Tegucigalpa. His smile and invigorating energy, seemed to hide a deep frustration and anger, which I verified minutes later. Garífuna cultures are currently facing processes of folklorization that freeze and sanitize their cultural practice. Outside of the development of urban centers their communities face a deep social and economic marginalization. The legacy of Garífuna resistance is still vibrant in the performative practices that shape the daily lives of the population in their political struggle blurring lines between art and life. In the capital of Honduras, Tegucigalpa, I met with the official representatives of the Garífuna culture and the representatives of the alternative cultural movements, such as the Garífuna Ballet, founded and directed by Armando Crisanto Meléndez. The ballet is one of the few examples of solid institutional platforms that have developed in Garífuna research and performative practices, with government support. Of course, this has not been without criticism or controversy. Conversing with Jorge Chavez, reminded me of the importance of understanding culture as a field of conflicts and negotiations -- never as a singular expression of collectivity. Chavez and Crisanto represent dialectical sides of Garífuna culture. Two questions are guiding my reflections on this research: the first is how to develop methodologies that challenge the relationship between subject, or research, and object investigation. I am thinking about how post-ethnographic approaches, based on performativity and research, may be porous processes designed from the experiences that communities allow. The second question is about the limits within and between curatorial and anthropological research. I am not interested in understanding the Garífuna culture as a form of Otherness to be translated. I am interested in how Garífuna's history of creative resilience can teach us about the potentialities of mestizaje and anti colonial aesthetics.

Part 2:

Image: Overview of Liviginston.

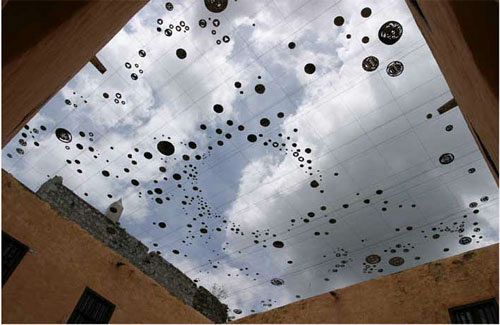

The history of the Garifuna has been unique, not just exemplary of the complexities of the histories of racialization in Central America and the Caribbean, but one that remains a vibrant testimony of a dignifying creative resistance that shares as many bonds with the African diaspora as it does with the local indigenous population. I began my travels where the first Garifuna settlement happened after exile (Roatan, Honduras), ending in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, where the story of Garifuna resistance begins. During the trips, two strategies guided my approach to Garifuna culture: long open conversations with key cultural actors, and the quasi archaeological work of finding traces of visual and performative culture, which encrypts and holds collective memory. The history of the Garifuna people is deeply entangled with the colonial memory of deterritorialization, with the constant idea of an ancient home being far away. These forms of memory are encrypted in visual, performative and spiritual practices that serve as strategies of survival. I tried to hold most of the meetings in places where the work of the people was actually taking place, including in restaurants or during dance practice, as happened with the Garifuna ballet in Tegucigalpa. These travels couldn’t result in a final statement around Garifuna culture, but more of an approach where different possible axes of inquiry are still to be discovered. For instance, one of the unexplored aspects is the Garifuna history is its diaspora in the United States. I was surprised to learn that more than 80,000 Garifuna currently live in the Bronx, for example. The ICI/CPPC Award allowed me to do the fieldwork that will lead to further research, essays or curatorial projects that can articulate a history of colonial resilience and resistance that manifests itself through a vibrant culture.