PREFACE

From Media to Metaphor is an exhibition of artists' responses to the AIDS crisis. Because no single artistic voice or viewpoint is capable of grappling with the complexity of the epidemic, we have selected works by dozens of artists that, en masse, evoke the impact of AIDS on American society and psyches.

It is clear that one cannot talk about AIDS—or art about AIDS—without raising contentious issues of sex and sexual identity, public health and private morality. In order to discuss these matters, the following essay assumes the unconventional form of a dialogue focused on AIDS and art's place in the midst of the crisis. Commentary about the works in the show, grounded in both social conditions and aesthetic concerns, can be found in another part of this catalogue. We believe that our dialogue is more likely to raise difficult questions than to provide easy answers.

In the face of a deepening and ongoing catastrophe, there is little room for the sonorous voice of authority, including the art historian's often reflexive impulse to categorize. The ebb and flow of our dialogue is intended as an analogue of AIDS-related social conditions that are continually—and messily—in flux. We hope that in conjunction with the exhibited art it will provide information, stimulate action to stem the spread of HIV infection, and foster more humane treatment for people living with AIDS.

—Robert Atkins and Thomas W. Sokolowski

ART ABOUT AIDS: TWO VOICES—MULTIPLE CONTEXTS

Thomas Sokolowski: In the fall of 1987 when I was working on Morality Tales: History Painting in the 1980s, an ICI exhibition of large-scale paintings about contemporary social issues, there were very few artists making art about AIDS.

Robert Atkins: Now there are so many—perhaps 500 professional artists in the United States who put AIDS at the center of their work.

While organizing the exhibition we certainly had the sense that one artist's work might stand for many who are dealing with similar aspects of the crisis.

When we began thinking about this show in early 1989, we also believed that not only was too little work about AIDS being shown, but that artists were sometimes penalized for making it.

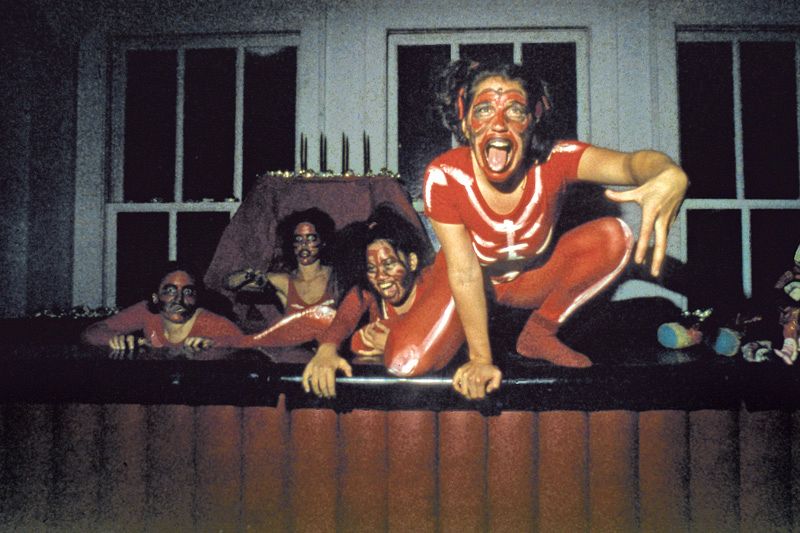

Meaning much of it wasn't—and isn't—saleable. What strikes me about the many projects produced for the 1989 Day Without Art [the national day of action and mourning in response to the AIDS crisis] is that so many were temporary, site-specific pieces. Some of the first AIDS-related works, then, were specifically commissioned installations that no longer exist.

And the corollary is that painters—operating in the most conservative, most commodified of art-making media—began to make work about AIDS after the installation artists you've referred to, and three to four years after the first photographers. The first major bodies of AIDS-inspired works were produced by photographers working in the modern, documentary tradition. They tried to combat the horrific representations of people with AIDS (PWAs) made by photojournalists and the electronic media.

That's where the media of the show's title comes from; it doesn't mean art-making mediums like paint-on-canvas or cast bronze.

AIDS was named in 1982; the first wave of photographers wasn't active until at least 1985 and not exhibited until 1988. The entire field of depicting AIDS had been left to the largely unsympathetic mainstream media. Perhaps the major exception was the NAMES Project Quilt, which debuted in 1987. Its heartbreaking—and unthreatening—emphasis on memorialization helped make the subject of AIDS palatable to those who read about it in People magazine. In retrospect, it's not surprising that so many photographers felt the urge early on to create sympathetic—or positive—images of PWAs, in conscious opposition to the exploitive and grisly media images that depicted them as if they were starving Ethiopian babies. Until the Rosalind Solomon: Portraits in the Time of AIDS exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery and the AIDS component of Nicholas Nixon's retrospective, Portraits of People, at the Museum of Modern Art in 1988, this photo-work was still rather underground.

One of the chief responses to those shows was acrimony. Whether perceived as negative or positive, these pictures occasioned an outcry among some activists. The objectors saw—and still see—Nixon's serial portraits as lacking in social context and creating emaciated monsters out of PWAS. But such exhibitions were rare in 1988 and these photos allowed the faces of individual PWAs to be seen. PWAs were regarded as individuals, rather than as statistics.

At least these photographers documented the reality of who PWAs are. Of the few TV movies about AIDS, for instance, only An Early Frost (1985) and Our Sons (1991) featured gay PWAs—and none have focused on drug users or their sex partners. Instead we see heroic depictions of ‘innocent’ victims who contracted the HIV virus through blood transfusions. The divisive media constructions of 'guilty' and 'innocent' victims were precisely what these initial, well-intentioned photographers were confronting.

Solomon's photographs were also more palatable than Nixon's because, in many cases, the PWAs she photographed look healthy—as so many HIV+ people or PWAs do. Nixon's work was more abrasive. For the first time, in a mainstream art context, viewers saw images of people who were visibly ill. Many people didn't want to see them and accused Nixon of undermining PWAs whose lives are difficult enough.

When a group from ACT UP [the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power] leafleted Nixon's Museum of Modern Art show, their broadside called in part for images of PWAs "who are loving, vibrant, sexy, and acting up." Yet some PWAs find Nixon's work a powerfully realistic representation of themselves. Solomon's and Nixon's works also suffer from the inherent limitations of the modern, documentary, black-and-white tradition that includes both photojournalism and so-called art photography. As a medical, political, and ethical phenomenon, AIDS is staggeringly complex. In an uncaptioned photograph, it's sometimes impossible to determine what's going on. Is it about AIDS? Or is this simply a generic picture of a young woman in a hospital? The context in which you see the work—an exhibition, a magazine, or a political demonstration—may largely determine its meaning.

The imaging of AIDS by artists almost immediately brought the conflicting needs of different audiences out in the open. On one hand, there was an ill-informed ‘general’ public and, on the other, insiders including PWAs and activists. How could there be one kind of image that would serve everyone's needs?

There is more agreement on another matter of representation, of ‘positive’ imagery—that is, the depiction of PWAs in language, and their preference for being called "people with AlDS" rather than "AIDS victims." Max Navarre, who was one of the founders of the PWA Coalition, said "I'm a person with a condition, I'm not that condition." Until the PWA movement emerged out of the Denver conference in 1983, there were no organized outlets for the views of those living with the syndrome.

Photographer Gypsy Ray would later respond to this void by insetting the comments of PWAs into the mats surrounding her pictures. Nicholas and Bebe Nixon's new book, People with AIDS (1991), includes extensive interviews. Both Ray and Nixon interviewed the care-givers and loved ones of PWAs, as well as PWAs themselves.

There's the cliché that in ten years everybody will be committed to doing something about AIDS because we will all know somebody who is HIV-infected. The present lack of connection between the public at large and PWAs, as expressed through language, is also something the Canadian art collective General Idea has been exploring in their artworks based on Robert Indiana's famous Love icon. Since 1987, they've appropriated Indiana's format and converted the four letters of "love" into the four letters of "AIDS." Some regarded it as a cheap trick—love being the emblematic word and activity of the ‘60s, and AIDS its corollary in the '80s. In fact, their stated intention was to "domesticate" the word, to communicate that AIDS is an unfortunate part of everyday life and not merely scientific jargon.

One purpose of this show is to present audiences with information about AIDS, as well as contemporary art.

Information about AIDS prevention, treatment, and community resources for PWAs will be available so that if a well-informed visitor comes to the show, he or she will find new information. And if you are someone who has never seen a PWA or considered the dilemmas that face PWAs, then this exhibition will provide information about that, too.

The show suggests a number of possible human and artistic responses to the epidemic. A problem with some AIDS exhibitions is that they have not overtly promoted activism—whether that means urging the public to contribute money or time for the care of PWAs, or to write letters to Congress, or to demonstrate at the Centers for Disease Control. Because all sorts of people in urban centers are affected by AIDS—people of color, gay and lesbian people, the health-care community, to name a few—the appeal of a show like this might extend beyond the usual audience for contemporary art. We want to make sure that informational and educational resources are available.

And that the exhibition speaks as directly as possible.

We've deliberately chosen works that are not ‘coded’ in the sometimes difficult-to-decipher, visual language of historical or contemporary art. We hope that these works will speak to varied audiences.

By its nature, this show engages contemporary art that is inextricably and immediately linked to its social context. Much of the art derives from artists' hands-on experience with PWAs—such as Paul Marcus's lengthy involvement with a young mother in the Bronx who subsequently died, or Dui Seid's experience as a home-care attendant for PWAs.

Many of the pieces in the show have also generated debate, beyond the narrow confines of the art world, about the representation of AIDS. Nancy Burson's poster, Visualize This., for instance, is an object of visualization for PWAs. She took photo-microscopic images of an HIV-infected and a healthy T-cell and made a poster from them. Its meaning was debated by funders from whom she sought production costs, and by people who saw the work wheat-pasted on New York walls. Detractors felt that it placed the responsibility for the AIDS crisis on PWAs rather than on the government. This position may be a polarizing example of either/or thinking not necessarily in the best interests of PWAs. Some PWAS employ Eastern and Western medicine, visualize and meditate, and participate in demonstrations as well.

Many of the artists in the show are PWAs; too many others have died of HIV-related causes. Their AIDS experiences, given form in art, teach by example. Being an artist allows you to take your life experiences—positive or negative—and make them the basis of your work. The shock of discovering your HIV+ status—or that of someone close—might be transformed into art.

Or perhaps action.

Wherever the show travels, its hosts will produce a local component that can be used as an organizing tool. The local component also allows for a kind of update, an opportunity to create dialogue between artists, care-givers, and service organizations.

It can give artists the opportunity not just to exhibit their work about AIDS, but to investigate local AIDS conditions. Every community has its own epidemic.

As we conduct this discussion in mid-May 1991, the Whitney Biennial has just concluded. Critics have noted that its thematic undercurrent is the AIDS crisis. The works range from the very pointed AIDS Timeline by Group Material [fragments are reproduced in this catalogue], to more subjective and indirect allusions that can be read as a generalized sense of angst, sadness, or anger.

A sort of emotional barometer.

This emotional barometer might be social, as well as psychological. The members of General Idea are Canadian, and they split their time between New York and Toronto. They see their work as very different from American art about AIDS. They feel that they can make art about what Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, in her book On Death and Dying, described as the third stage (acceptance) of coming to terms with death, partly because the Canadian government has been so much more responsive to the needs of PWAs.

AIDS is an emotional barrage. In the face of so much death comes overwhelming grief and anger. Thomas Woodruff spent months painting self-portraits of himself as a crying clown. The texts of David Wojnarowicz's works are shockingly direct in their rage. The emotional range of recent AIDS art seems to be widening. The anger of a work by Donald Moffett that reads "Call the White House and tell Bush we're not all dead yet" is tempered by a defiant and liberating irony. What some viewers might dismiss as mere propaganda is leavened by mordant wit.

Moffett's subversive use of media and advertising techniques is also very contemporary. How does art about AIDS relate to art about earlier social crises?

The art world has changed drastically during the past two decades. Thanks in large part to feminist-inspired pressures of the ‘70s, even very mainstream artists acquired ‘permission’ to abandon abstraction, to make figurative art, and still remain in the mainstream. To cite just one example, Leon Golub made compelling paintings twenty-five years ago about soldiers in Vietnam, and later about mercenaries in Central America. One of the reasons that the earlier work didn't get much attention was its distance from the stylistic mainstream. Now there is no single ruling mode of art-making. The socially engaged coexists with the most determinedly formalist art; abstract painting shares the spotlight with artworks on billboards. The current pluralism makes it possible to hear from those who have never before been allowed to speak. These marginalized voices are highly attuned to the tremendous social problems facing the United States. In many cases, the artists have experienced those problems, including AIDS.

Art that responds to social crisis brings to mind art produced in Siena during the Black Death of the fourteenth century. It tended to be emblematic and to adhere to a very specific canon of beliefs promulgated by the Roman Catholic Church. Prayers to Christ himself, or to the Blessed Virgin or saints who would act as intercessors to God on one's behalf, would be accompanied by vows. If a town was spared from the plague, an illness cured, a child born healthy, prayers of thanksgiving would be linked to the production of an ex voto painting as a l sign of gratitude. Thus the artwork was made afterward; it was retrospective.

And it also embodied the collective beliefs of those in power, in this case representatives of the Church and State. It seems safe to say that an artist is always commissioned to represent a patron's point of view.

Closer in time were the FSA [Farm Securities Administration] photographs commissioned by the federal government to document the rural woes of the Depression. They were intended to prove whether the troubles that government officials in Washington, D.C. had heard about were as bad as reports indicated.

There's something like that happening now on a modest scale. The Library of Congress is collecting documentary photographs about AIDS.

During the Depression, the government's role was not so adversarial. The impact of the economic crisis was being documented by photographers and ameliorated by New Deal legislation.

The overt depoliticization of postwar American art—which can in part be traced to artists' and intellectuals' revulsion to the cynical Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939–dominated American art of the 1940s, '50s, and '60s. Postwar existentialism was translated into the psychologically-oriented abstract art of the mainstream. Today it's difficult to imagine abstraction's stronghold on art production. During that period, overt political expression—such as Warhol's anti-Nixon prints for the McGovern campaign—rarely surfaced in the work of well-known artists.

Warhol is certainly the progenitor of so much media-inspired, activist art about AIDS, whether it's intended for the gallery or the street. He understood that the modus operandi of Madison Avenue might be applicable to SoHo. Gran Fury—whose very name evokes a ‘60s-model Plymouth—makes their art and politics inseparable, including their manipulation of the media as a sort of stand-in for audiences who can read about, rather than see, the work. One buzzword of the ‘80s was strategy, and sometimes the strategy became the artwork's concept.

And there are other kinds of strategizing as well.

The art world has rarely displayed such solidarity as it has in connection with AIDS. The commitment has come from artists, critics, and curators. Art is also a useful fund-raising tool. Art Against AIDS auctions donated artworks to raise money for AmFar [American Foundation for Aids Research] for medical research. At Visual AIDS in New York, art is used as an educational tool. Another Visual AIDS group in San Francisco raises money to help PWA-artists buy art supplies. There are collectives like Art+, in New York, which produce programs, as well as demonstrate. This list only scratches the surface.

Some of the art world's solidarity about AIDS also derives from the many attempts to censor art about AIDS, particularly explicitly sexual imagery produced by gay men. Openly gay and lesbian artists are commonplace in the mainstream art world. If the AIDS epidemic had initially hit IV-drug users, it would have been difficult to predict art-world involvement. This is largely a matter of class; professional artists tend to be middle-class. An unfortunate by-product of gay and lesbian leadership of AIDS awareness and activism efforts is that it plays into the hands of those who cynically manipulate homophobia—sometimes by attempting to censor publicly funded art. Art about AIDS frequently invokes political outrage or attitudes toward sexual activity and that's led to some bruising controversies. The first involved an attempted withdrawal of NEA support for Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, the AIDS exhibition that was John Frohnmayer's first crisis after he became chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts in late 1989. AIDS was also the subtext of the Robert Mapplethorpe controversy and trial, although homosexuality was the censors' pretext.

An early and articulate voice in writing about AIDS and sexual repression was Simon Watney, the author of Policing Desire: Pornography, AlDS, and the Media (1987). Although the book focused on Britain, the handwriting on the wall is disturbingly clear. A government-condoned sexual panic exacerbated by AIDS has created a climate in which the British government is attempting to recriminalize the activities of sexual minorities.

What's most surprising is that the virulent assault on American freedom of expression has been so effective. It's partly a problem of misleading sound bites and misrepresentations akin to the characterization of a publicly sited AIDS artwork by Gran Fury called Kissing Doesn't Kill: Greed and Indifference Do as an "enticement to homosexuality." And painter Kathe Burkhart has depicted Elizabeth Taylor, AIDS fundraiser and activist extraordinaire, defending herself against "charges" of having AIDS—as if having AIDS were a crime and would render her generosity suspect.

The Right understands the power of symbols. Because symbols are richly ambiguous, they are easily manipulated. Look at the Cross: it can stand for the most liberal theology of the Unitarian Church and its virtual opposite, the Ku Klux Klan. Art itself—as opposed to individual artworks—is also symbolic. It partakes of the authority of the gallery or the museum—from a work's literal and figurative location on a pedestal or in a frame. For many people, art is a potent enigma and if it's perceived as an attack on long-held values or beliefs, then it's understandably frightening.

If some want to prescribe what kind of art artists should make, others are likely to prescribe what kind of art this show should present.

It is likely to incite criticism from several directions. For some viewers the imagery may be overly explicit. Others would curate a show like ours with exclusively didactic intentions, an explicit agenda that every artwork about AIDS must overtly concern itself with ending the crisis. This seems too doctrinaire.

How can anyone anticipate the effect an artwork—or a group of artworks—will have on a variety of audiences?

Maybe this exhibition is unusual because we acknowledge a sometimes blurry divide between art and activism; we don't always see them as synonymous. Good politics do not necessarily make for good art.

Bad political art is bad politics and bad art.

There are certain subjects that a society may deem unrepresentable. That is, they cannot—or should not—be addressed by artists because they are regarded, in some sense, as sacred.

As a [Jewish] child, it was clear to me that the Holocaust was something that couldn't—or shouldn't—be represented. Its awesome hideousness rendered it unimaginable. But that prohibition seemed to disappear over time, and there was a point in the '50s or '60s when plans for Holocaust memorials began to be formulated. Originally they were to be dematerialized and abstract, in the form of an eternal flame, for instance. But by the ‘70s, George Segal could make his figurative sculpture-memorial. Time must have lessened the shock and undermined the taboo against representation.

Memorials have assumed so many forms. Rudy Lemcke's proposal for an AIDS memorial in San Francisco is abstract—a meditative Zen garden. The Vietnam Memorial is simply a black wall with names on it. It's not inherently horrific, but that palpable roll-call of 56,000 names is extremely moving. How can we not be touched when we see all those names, even if we don't read them, even if we don't know anybody who died? Art allows public and private grief to coexist. When you rub your finger over your brother's name it becomes a personal act of mourning. But it is also about a nation's loss—its loss of naivete, of the glorious promise of post-World War II America.

The names inscribed on the Vietnam Memorial make it shockingly specific but as ordinary looking as a telephone book. I saw the memorial for the first time in 1987, the day before the NAMES Project Quilt appeared on the Washington Mall. A brilliant work of community art, the Names Project Quilt vividly testifies to individual diversity. In an entirely different way, one is also aware that each of the 56,000 names on the Vietnam Memorial stands for the passing of an individual.

An extraordinary thing about the quilt is the collective quality of the viewing experience as it travels from place to place. Of course, it is profoundly touching to see someone kneeling and crying at a lover's—or child's—quilt-square. But then your own tears might flow, quite independent of the specific thing being seen.

Again, the personal and the collective.

There are two sentences that Susan Sontag wrote in the first pre-AIDS version of Illness as Metaphor (1977) that suggest a split that cannot be bridged. She wrote, "Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place." When one is in one kingdom, one cannot even contemplate the other. And yet, at some point, our position will shift. The same thing is true of art, in the sense that art too can be so rarefied, so removed from so many people's daily lives. If you're uninterested in art, you may not understand—or care to understand—what artists are doing, and what it might mean.

You're speaking in metaphors. Can art save lives?

Not directly. But it can help the rest of us live.

—September 1991