Following the opening of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at the Hunter College Art Galleries in New York, ICI Exhibitions Intern Kiara Ventura talks with exhibiting artist Joey Terrill about his activism in the Chicano gay liberation movement of the 1970s, the origins of his zine Homeboy Beautiful, and his current projects.

Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. is curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz and was on view at the Hunter College Art Galleries from June 22 to August 19, 2018.

Joey Terrill's extensive work speaks volumes about the development of the Chicanx queer art movement in the 1970s and beyond. Grounded in the narratives of the L.A. queer community in which he grew up in, his work boldly crosses worlds between Chicano machismo culture, the gay Chicano community, the HIV/AIDS crisis, political activism, and more. Print media, T-shirts, and collages are all vehicles for his message regarding how stigmas are affecting the queer community on large and miniscule levels, and despite this responding fearlessly with creativity, artistic expression, and unity. A message that perfectly embodies Axis Mundo.

Kiara Ventura (KV): How would you best describe what it felt like to be a part of the 1970s Chicanx queer movement in L.A.? And, how would you describe the movement looking back?

Joey Terrill (JT): Regarding the 1970s and what I would refer to as the “Chicano gay liberation movement,” it felt new, fresh, and open to possibilities. We, including feminists and other socially progressive activists seeking change, all had this sense that what we were doing was pioneering a new society. There was not a previous “queer Latinx social or art movement” that I could reference or build upon, so we were making it up as we went along. Having said that, it was also a little scary.

I marched in the Chicano Moratorium where I was tear-gassed and subjected to police brutality.(1) But I was also concurrently involving myself in exploring my gay identity. I was a member of the Metropolitan Community Church youth group where I met other teens some of whom ended up being really close friends. I attended the “Gay-In’s” at Griffith Park, which were queer versions of the “Love In’s” public gatherings sponsored by hippies. I also participated in the youth group at the Gay Community Center in LA and became a member of the speaker’s bureau. So when I was around 18 years old, I would go to public school classrooms as a featured speaker to address classes about the gay community. I traversed both worlds of Chicano Power and Gay Liberation. The two were separate worlds that I was determined to combine.

At the same time, I was also an artist and in LA. Art was a big factor at least visually in the movement. There was a vibrant Chicano art scene that included ASCO and many artists were LGBTQ. The arts community in the 70s Chicano scene in LA seemed mostly open to accepting artists of every orientation…we were all artists! But of course, there were conflicts, debates and sometimes lots of love! One has to remember that there was no social media or Internet. We engaged with one another face-to-face, physically present, and in the moment. Our strategies for engagement meant we met at bars, clubs, and homes. Us young Chicana/os attended backyard parties, when the parents were on vacation or visiting relatives in Mexico. We listened to records, slow danced, and made out like other teenagers. When I entered a club packed with gay men or Latina/o gays and lesbians, it was thrilling to be among so many gay people! When I was 11, I remember hearing that there were gay people in Greenwich Village in NY and in San Francisco. I knew there were some in LA but I was sure there probably weren’t any Mexicans. By the time I was 13 and had my first sexual experience, I realized there was a whole world waiting to be explored, investigated and embraced. And I pursued it with passion.

KV: With the help of close friends and fellow Chicano gay artists, your 1970s publication, Homeboy Beautiful, critiqued the problematic machismo behaviors that stood in the way of uniting Chicano men. This was an act that was way ahead of its time and created a catalysts for mobilizing the LA Chicano queer community and zine culture in general. Why was it important to associate the homeboy or gangster culture with that of the gay community? Why did you make this space of imaginative sexual expression for gay Chicano men in the print world? Why was it needed?

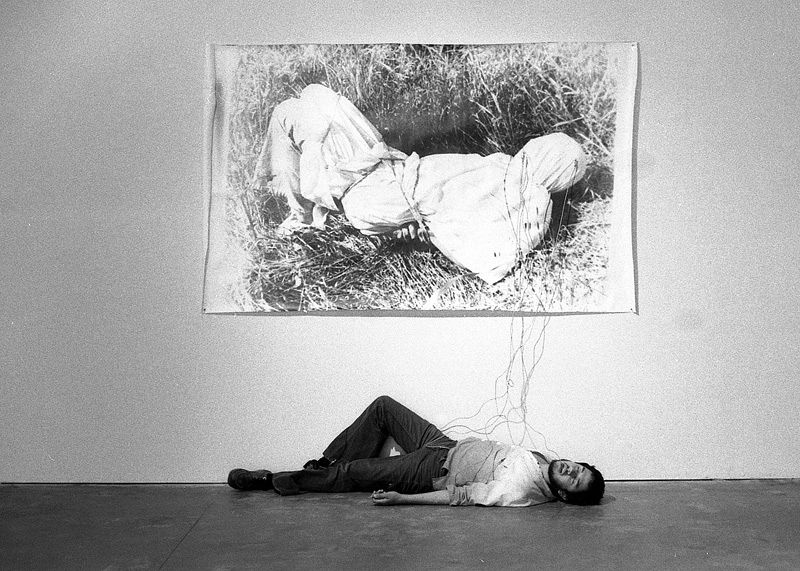

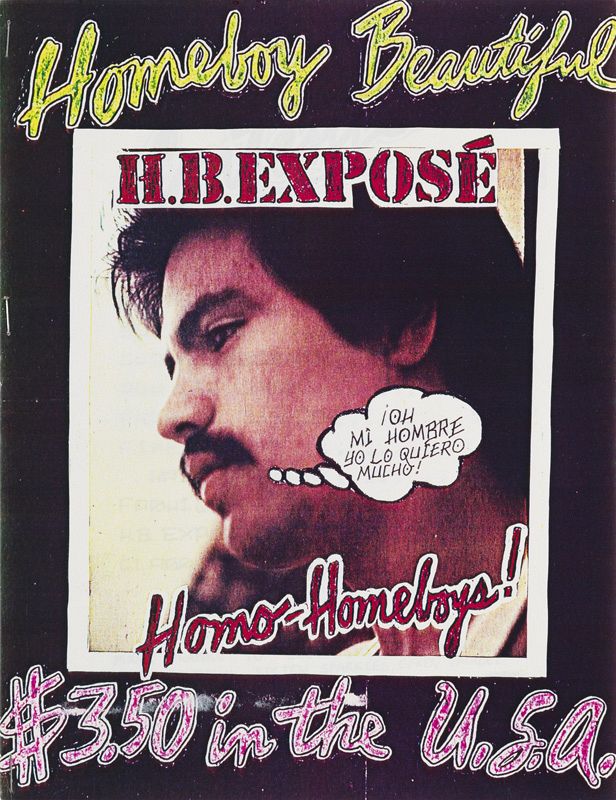

Joey Terrill, Homeboy Beautiful, no. 1, 1978. Self-published magazine, 11 x 8½ in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm). ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Courtesy of Joey Terrill

JT: By 1977, when I started to put down ideas and sketches for Homeboy Beautiful, I had experienced machismo behavior among Chicanos where their own internalized homophobia made them prone to violence, fighting, petty jealousies and unnecessary drama. I had experienced brawls and fights at clubs. Rival groups from neighborhoods imitated the gang warfare of the barrio, which I always thought was just stupid. We faced so much societal oppression, police brutality, and indifference to our poverty and lack of educational opportunities. Yet we’re going to fight one another because we come from different neighborhoods…? Give me a break. I was always a “sissy,” meaning I did not like violence. I didn’t like football or having to measure up to some standard of “macho.” To borrow from the Vietnam War protests, “make love, not war” was my motto. So I had been thinking of how to make art about all this: the homophobia within the barrio and within the Chicano Power movement with their focus on “La Familia” which excluded LGBTQ family members. At the same time, I was thinking about the invisibility of Latinos in the dominant white popular culture that was also reflected in the mostly white burgeoning “gay community and political activism.” I had attended Immaculate Heart College (73-76) and some of the artists there—Skot Armstrong and my gay Chicano artists friends Teddy Sandoval, Jack Vargas, Mundo Meza, and others—were doing variations of Mail Art. I knew I wanted to parody upper middle class magazines like House Beautiful, Cosmopolitan, and New West in which Chicanos did not exist. This was also a time of certain artistic endeavors that were radical in their un-political correctness: The Cockettes from San Francisco, John Waters and Divine (before they went commercial), Monty Python, performance artists, Warhol superstars, Teatro Campesino, Glam Rock, gender-fuck, Black is beautiful, radical protests, and punk. To varying degrees these were all percolating in my head and the idea of a magazine format to address and explore these issues came to me. The magazine was truly a collaborative effort where I asked friends and other artists to pose for a photo shoot for a specific segment or storyline and everyone loved the idea.

For gay Chicanos, I wanted to see and perhaps needed to see us in popular culture even if it was in a humorous format. The magazine was featured and available for purchase in three LA venues: The Soap Plant in Silver Lake (now, Wackos/Luz de Jesus Gallery), Chattertons Books in Los Feliz (now Skylight Books) and A Different Light Bookstore, Silver Lake (now closed). These venues were in the areas of town that gay people were frequently around which included Chicanos, but there were no options for venues in East LA. If there had been a venue on the Eastside, the sad reality is that the store or I would have gotten a bad response from cholos or homeboys that felt threatened, confirming my premise for the necessity of creating Homeboy Beautiful in the first place. While I didn’t consider myself a cholo and was never affiliated with a gang, I found myself very attracted to homeboys and some cholos! They were hot and handsome. And many times, they exhibited what I would call gentlemanly behavior: respectful of the elders, the abuelos, good with kids, and proud in good way. I dated one, Ronnie Garcia, who was handsome and a real sweetheart, except when he got drunk. When inebriated, he became a monster, filled with his internal conflicts over his macho identity. Only lasted 6 months. There’s more I could go on about, but I will have mercy on you!

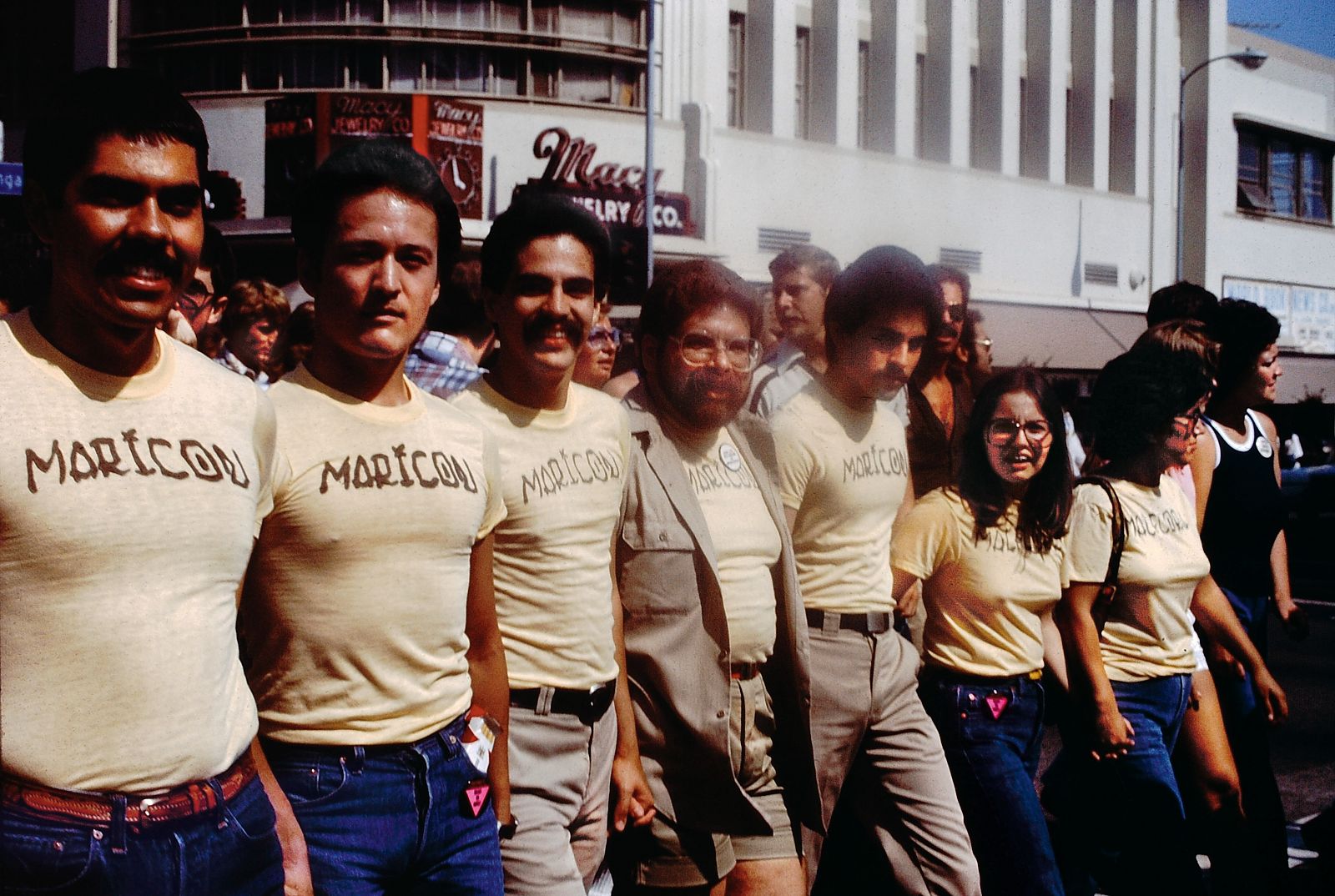

KV: When your line of malflora and maricón t-shirts made its first debut in the 1976 Christopher Street West Parade, it gave a direct spotlight to queer Chicanos/as and represented them as active participants in gay and lesbian activism. As we both know, nowadays representation is key. What did this radical act of representation mean to you at the time? What moved you to create this piece?

JT: I had been involved with the gay community as a teenager since I was 15 and recognized that Chicanos were underrepresented, if not invisible. I had marched the year before with my cousin Pat and her partner, my friend Martha. I had made a t-shirt with iron on block-felt letters that said,“Faggot” and one for each of them, saying, “Dyke” and “Lesbian.” I realized that I needed to do a maricón version.(2) I asked my friends and they loved the idea. This time I hand lettered each with textile dye left over from a class at Immaculate Heart. My friend Martha didn’t know if the slur was “manflora” or “malflora.” We decided that we liked the idea of a “bad flower” and went with “malflora.” I believe I made two of those for cousin Pat and Martha and then ten Maricon t-shirts for my friends who were marching and wearing them. The photo of us marching was taken by Teddy Sandoval who was wearing his shirt at the time. Latinos and Chicanos loved them and cheered as we marched. Some white folks didn’t get it but I think most did as well as our black brothers and sisters. I felt like we were asserting our identity not only to other Latinos but to other gay people as well. Discussions or conversations in the media usually portrayed the “gay lib” movement as white and separate from the Chicano power movement and activism. We were determined to challenge that.

Along with the name Maricon and Malflora on the fronts of the t-shirts, I felt it was important to put “ROLE MODEL” on the backs. It was a buzzword at the time. In debates about gay rights in the 70’s there was the argument that LGBT people were not good role models for children. That is an underlying homophobic argument for urging homosexuals to stay in the closet. When Proposition 6, or the John Briggs initiative, was on the California ballot in 1978, it called for a ban on homosexuals being teachers. The argument was that homos would not be good role models for students. It was a not-so-veiled reference to the idea that homosexuals are predators and child molesters who need to recruit young people since we could not reproduce like heterosexuals. At that same time within the Chicano Power Movement, the central cultural identity was based on “La Familia,” with the man (husband and father), woman (wife and mother) and children defining the patriarchal and misogynistic standard. This was the identity to which gay people were compared and excluded. It presented a similar argument that gay people could not be good role models for La Familia and signaled that there was no room for us in the Chicano identity. The t-shirts therefore declared us as role models for the white gay community as well as the Chicano heterosexual community.

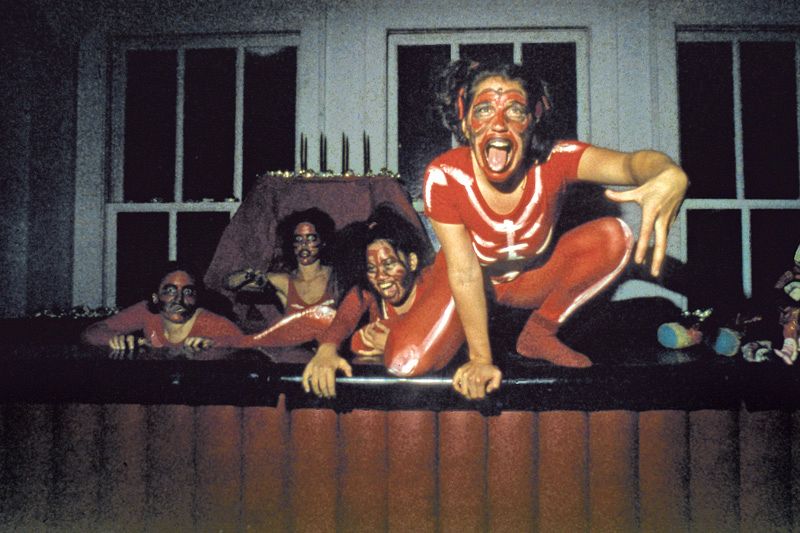

Participants in the Christopher Street West Pride parade wearing Joey Terrill’s malflora and maricón T-shirts, June 1976. Photo by Teddy Sandoval. Courtesy Paul Polubinskas

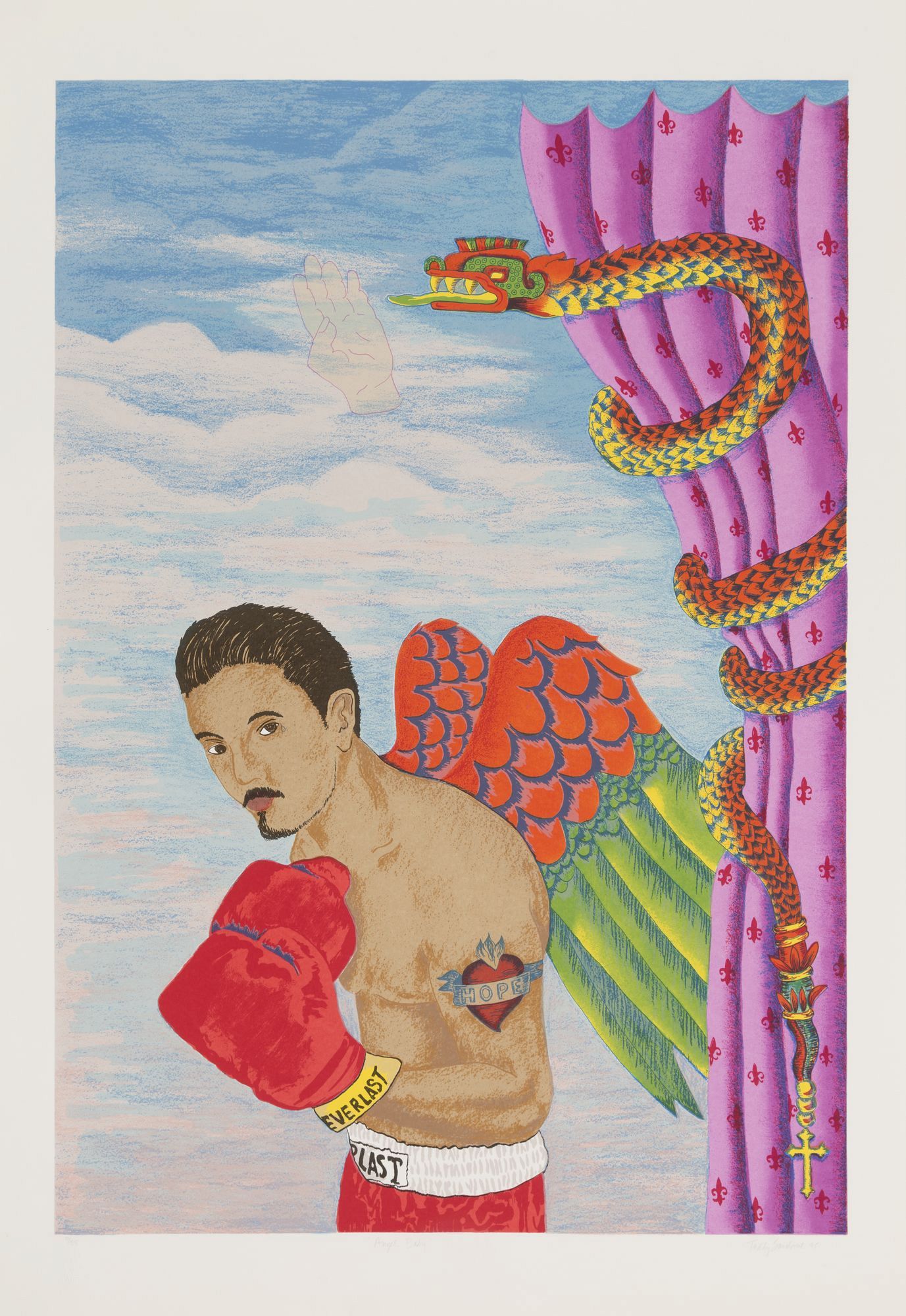

KV: For the last two decades, you have been working on your series of still lifes, emphasizing the normalization of living with HIV/AIDS. Here you place drugs that treat these conditions alongside mainstream consumer products and domestic spaces that reflect Chicana/o and queer culture. Why did you choose to communicate this message through consumerism?

JT: I had reached a point by the mid 90s where I realized that anti-retrovirals were going to keep me alive. I had always assumed that I was going to die from AIDS. My friends were dying all around me: my classmates, my ex-lovers, my dance partners, my work colleagues, my best friends, disco friends, artists, musicians, bartenders, band members were all in various stages of dying and there was nothing that made me think I would be any different. I had also been working as the coordinator of the HIV and Vision Loss Program at the Center for the Partially Sighted. I helped develop this program, which specifically worked with individuals (mostly men) who were going blind from an AIDS related opportunistic infection, usually cytomegalovirus retinitis (CMV), or toxoplasmosis, shingles or the worst, Progressive Multi-focal Leuco-encephalopathy (PML). By that time people were negotiating and suffering from multiple opportunistic infections and intense side effects. They had 12 different medications to take and go to multiple doctors’ appointments, all while they were going blind. It was horrifying and disheartening. People got severely depressed and would give up. The average age range was roughly 21 to 50 and their average life span at that point was about 6 months. I would conduct home visits and determine what kinds of independent living skills techniques for the blind might assist them with maintaining independence – being able to tell their meds apart, tell time, negotiate the bathroom safely, instruct family and friends in sighted guide technique, etc. Every time I visited someone, I thought, “Will that be me?”

As an artist the thought of going blind was incredibly frightening to me. So when I realized I was probably going to live as my antiretroviral therapy (ART) was going to keep me alive, I had ambivalent feelings about it. While I appreciated that the drugs were keeping me alive, I also knew that the drugs were products that were making billions in profits for the pharmaceutical industry and were a product like Coca-Cola, Peter Pan peanut butter, or Cheerios. I have been and remain an ardent advocate against the price gouging by Big Pharma, not just on HIV meds, but across the spectrum of prescription drugs and how they control the conversation on healthcare in the USA.(3)

I was trying to figure out how to indicate my ambivalence and was hard pressed to come up with a specific image that would show that. I also knew that I wanted the work to be about the drugs in our capitalist consumerist culture. While sitting at the breakfast table one morning, I thought about the pop art still lifes of Tom Wesselmann, which I always loved. His juxtaposing adverts from American consumerist culture both celebrated and critiqued the society they represented. My intent was to borrow that still life trope and both Mexicanize and Queerize the imagery within work so the Chicano artist origins would be clear. But what I also like to think I’m doing is bringing HIV drugs, which are seen as foreign and scary to so many people, into work that contains familiar imagery. People recognize the still life genre. They relate it to seeing a Mexican blanket on a tabletop, flowers, fruit, or a bottle of Rompope. Sometimes people look at the work and say, “Oh, I love the floras.” They recognize products even if they don’t know what Viracept, Crixivan, or Truvada is. It is bringing the unfamiliar into a domestic space to which they can relate. I am fine with whatever path one takes to appreciate the work. I like to think that I am both expanding the definition of what constitutes Chicano Art and making art about AIDS that doesn’t look like art about AIDS.

KV: Your work featured in Axis Mundo speaks to the lives of the Chicanx and queer community. Homeboy Beautiful and the malflora and marícon T-shirts speak on political and cultural issues from back then that are still present today. Do you plan on building off of these projects? What is next?

JT: I’ve always explored appropriating different genres and cultural iconography to rework into my own Queer Chicanx agenda and what I’ve decide to do now is to take on the current exploration of identity from “preferred pronouns” to “Latinx” versus “Chicano” as an identity. In this day and age of social media bombardment and ubiquitous proliferation of “the selfie” and identity (especially politically correct tribalism), I am choosing to go backward, leaving the 21st Century and finding inspiration in a genre I have been fascinated by: 18th Century Castas paintings. My new work is called the Mi Casta es su Casta series. These will be portraits of friends and artists, painted in that centuries old style but with the individual determining their racial identity (rather than the artist labeling them). I’m also including sexual orientation or identity. While I am allowing for all the designations from Latinx, Chicanx, Queer, Lesbian, Non-gender-conforming appellations, it’s a little bit of a finger wag to young people who seem especially strident in their embracing of a particular identity as they “correct” others about how they want to be identified. When asked on a panel discussion for my preferred gender pronouns, I replied, “I don’t give a fuck.” Call me whatever you want: she, girl, it, boy, etc. I am in no way challenging or disrespecting anyone’s right to determine their identity. I would also never intentionally mis-gender a person. With my declaration I am trying to make a space for those of us for whom a gender identity is not a priority. People have called me “girl” or “she” as a slur growing up. While I used to be hurt or insulted I’ve reached a point where I don’t care what someone else calls me because I know who I am.

1 The Chicano Moratorium was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that created a coalition of Mexican-American groups to organize against the Vietnam War through demonstrations and staged walkouts.

2 Maricón is a derogatory term meaning homosexual man, queer person, or coward in Spanish.

3 Big Pharma refers to conspiracy theories claiming that the global pharmaceutical industry operates for negative purposes and is against the public good.