Marina Reyes Franco, recipient of the 2017 CPPC Travel Award, writes in-depth about her research trip to Trinidad (September 2017).

A huge photo of a beautiful beach welcomed me to the immigration line at Piarco International Airport in Port of Spain, Trinidad. “Gorgeous span of Maracas Bay,” said the caption, “where locals and tourists alike enjoy the sand, sea and sun.” I never went to Maracas Bay, but I could tell that, by emphasizing that “locals and tourists” go to the same beach, they meant this wasn’t your regular Caribbean all-inclusive destination. For someone interested in the visitor economy, Trinidad might seem like the wrong place to start this research. After all, the island’s economy is heavily dependent on natural resources like petroleum and natural gas, and the capital Port of Spain is hardly a cruise ship haven or a resort hotel town. However, the island connects to another line of research that I’m particularly interested in: the US military occupation and its cultural and political repercussions in the Caribbean region. I’d been wanting to come for several years now, and now it was finally possible. Similar reasons would also lead me to schedule Panama as my next stop in this research tour of the Caribbean and Central America.

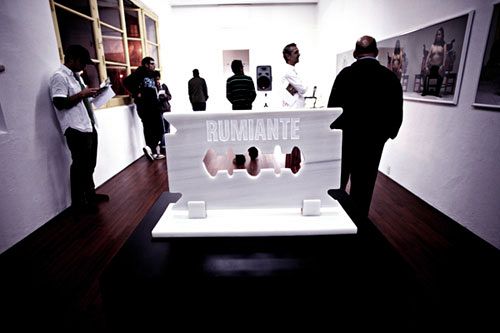

Image: A CLICO ad from 1993 commemorating independence. Renamed CL Financial, CL Financial was the largest privately held conglomerate in Trinidad and Tobago and one of the largest privately held corporations in the entire Caribbean, before the company encountered a major liquidity crisis and the government bailed it out in 2009.

American presence and interventions in the Caribbean have varied according to evolving policies in relation to the Monroe Doctrine, the Roosevelt Corollary, the Good Neighbor Policy, WWII, the Cold War and, lately, the War on Drugs. North American influence in the Caribbean became stronger in the late 19th century due to the United States replacing Europe as the hegemonic power in the region and the increasing economic ties to the US and, to a lesser extent, Canada in terms of trade and investment. The US also became a common destination as Caribbean peoples migrated out of the region in large numbers for the first time. Expansion beyond the shores of the North American continent seemed the inevitable consequence of Manifest Destiny but, even though influence in the Caribbean was in its geopolitical interest, making them American territories to be settled and given full membership rights was not an objective. The new US imperialism dictated by the Monroe Doctrine, which declared that the European powers should not interfere in the politics of the new American republics or seek further colonial possessions, made implicit that this hemisphere was the natural world-region of US hegemony. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt announced the so-called Roosevelt Corollary, a declaration that while the US had no intention to take territory, they would make sure their neighbors were stable, prosperous and orderly, thus assuming the moral right to intervene whenever it felt these conditions did not prevail. Numerous occupations followed in Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Haiti in the next couple of decades, particularly during World War I. In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted the Good Neighbor policy, encouraging friendly relations and mutual defence among the nations of the Western Hemisphere. Hardly an accord between equals, it nevertheless led to the end of military occupations by 1934.

A new relationship between the US and the Caribbean would develop following a pretty straightforward 1940 Destroyers-for-bases deal struck with the United Kingdom, in which land was ceded to the US in a 99-year lease with the purpose of establishing military bases in British colonies. US Army, Navy and Air Force bases sprung up in Bermuda, Newfoundland, Antigua, The Bahamas, British Guiana, Jamaica, St Lucia and Trinidad. I’m particularly interested in the US Navy base in Chaguaramas. There, people were evicted, bathing beaches were declared out of bounds, and by 1942 the whole peninsula was a military base strictly forbidden to the public. At its peak during World War II, there were some 30,000 resident U.S. troops and, during the Cold War, the peninsula was also host to one of the six Ballistic Missile Early Warning System stations located all over the world. After many protests in the early 60s and achieving independence in 1962, a period of tense negotiation ensued and the land was transferred back to Trinidad and Tobago in 1967. One of the many plans for Chaguaramas included it becoming the capital of the short-lived West Indies Federation.

Image: Commemorative plaque in Chaguaramas.

I am interested in the shared postcolonial history of these countries and territories and their relationship to the history I’ve experienced in Puerto Rico through the occupation of the island municipalities of Vieques and Culebra, the Roosevelt Roads Naval Base in the town of Ceiba and numerous other bases around my country. My intention was to take a closer look at these territories in Trinidad and Panama since the occupation ended, to establish relationships between places that have been considered important because of their geographically strategic positions, thus becoming -at different points in time- indispensable to U.S. interests. I also looked at the redevelopment of the Canal Zone in Panama after 1999, and the “Development Authorities” that have sprung in Roosevelt Roads and in the Chaguaramas Base in Trinidad to repurpose those post military spaces with sometimes highly questionable development models.

I only have a vague memory of perhaps having visited Trinidad on a cruise ship when I was a child, but I can’t really be sure. The nature of cruise ship travel is like that - sometimes you don’t even know where you are, but there’s a buffet and ice sculptures waiting back on board. All I know about this country is through books, movies, music, friends and the work of some of its artists, many of whom I’ve only gotten to know and talk to via chat and email in as part of a growing network of potential collaborators who I would finally meet on this trip. The English-speaking Caribbean is particularly new and interesting to me, as its history represents other decolonizing discussions, theories and characters that haven’t been part of Puerto Rican political life−not even in the Left−in recent decades. However, one Caribbean figure is central to Puerto Rico: Sir Arthur Lewis of St Lucia, whose “industrialisation by invitation” approach was most dramatically implemented during “Operation Bootstrap,” and we can’t seem to escape even today.

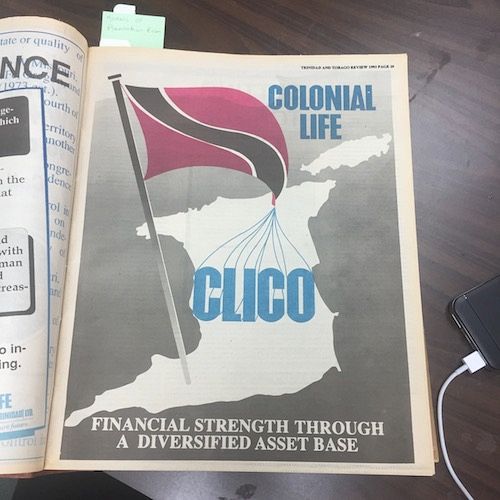

Image: A nationalist palm tree outside the Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago

I arrived to Port of Spain during the first week of September, just a few days after the August 31st independence day celebrations and the red, black and white colors of the Trinbagonian flag still decorated every government building, bank and fast food restaurant in the city. An oil economy has so far spared Trinidad what one might call the indignities of the tourism trade in the region, but persistently low gas prices, numerous corruption scandals and a contracting economy have also left the country in a recession. It’s clear that the country’s economy is long overdue for diversification, but conflicting political parties and economic interests can’t get on the same page long enough to enact any long term policies. Right now, the tourism industry is mostly business related, with Trinidad, as the bigger island with more infrastructure, serving as a regional conference and banking hub. Whereas Trinidad is industrial and more business-like, Tobago is widely understood as the island with more tourism potential. The government is in talks to open an all-inclusive Sandals resort but ironically travel there is hampered by inefficient ferry transport, though I guess resort guests would fly in directly. Only locals worry about ferries, anyway. Around the time of my visit, Mark Bassant, an investigative journalist known for explosive exclusives, was called to give testimony in Parliament in a recent corruption case he uncovered involving mismanagement of funds allocated to acquire a new ferry for Tobago. I was surprised when Bassant, whom I contacted through Twitter, agreed to meet and discuss his recent investigations and upcoming testimony. His "A Gap in the Bridge” 13-part series exposed the underlying corruption in a ferry lease agreement between the Trinbagonian government and a Canadian company of dubious origin whose smaller, older, more expensive and constantly breaking down ferry was selected over a European competitor. I will say one thing about Port of Spain, though: it’s a city that turns its back to the sea. In fact, one of the few spots in the city where you can really see the Gulf of Paria is from the Hyatt Regency hotel waterfront walkway. This hotel is so important for the economic and political elite, only a driveway divides it from the new Trinbagonian parliament building. Their exterior architecture is so similar, it might as well be another hotel tower.

Image: Christopher Cozier and Kriston Chen in Alice Yard.

In what definitely turned out to be the best introduction to the region, I was hosted by artist Christopher Cozier in Alice Yard, the art space and residency he co-founded in 2006 with writer Nicholas Laughlin and architect Sean Leonard in the former house of Leonard’s great-grandmother. The yard, is it is commonly called, is a 1930s house with a small apartment for residents, studio space, a small exhibition space, a rehearsal room for local bands and yard itself, where everything happens. Many projects are currently run out of the yard: Out of Place is a curatorial collaboration between Cozier and Bahamian artist Blue Curry which takes art into the public space of bus stops and squares; 1000 Mokos, which organizes urban youth to learn how to walk on stilts in the Moko Jumbie Mas tradition; and toof prints, a project by designer Kriston Chen -also part of 1000 Mokos- that invites other artists to explore contemporary graphic design in the public space - an unused wall at the yard. Granderson Lab, an off site project of AY, provides studio space for several designers and artists in a warehouse building. See You on Sundays is an elastic group of artists - Alicia Milne, Alex Kelly, Luis Vázquez Laroche, Nikolai Noel, and Wasia Ward are its founding members - who meet to discuss texts and socialize about their respective artistic practice. They are part of the younger generation of artists AY, and Cozier specially, want to see grow into their own, despite the lack of local financial or institutional structures to support contemporary art practice. Some of these artists have already visited Puerto Rico before as part of a growing partnership with Beta Local, the San Juan-based arts organization.

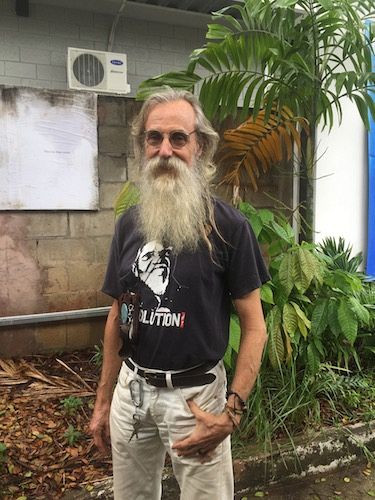

Image: Artist, bioregional animist and implementer of the permaculture model, Johnny Stollmeyer.

Starting in 1997, Cozier had been part of CCA (Contemporary Caribbean Arts), a regional developmental organization based in Trinidad that encouraged Caribbean artists by supporting and fostering exchanges between local and international artists. Perhaps growing into a too ambitious project, in 2000 CCA established CCA7, a 20,000-square-foot facility that houses 2 galleries, 13 artists’ studios, archives, a library, and educational, lecture and conference spaces, in Laventilla, the nation’s poorest neighborhood. Though it was important in connecting regional cultural agents, it failed to connect with a larger audience locally. CCA7 announced its closure in 2007 citing that, despite increased international funding, the “lack operational funding or much in the way of communal national support” in Trinidad made the continuation of the project impossible. According to Cozier, there is a myth that contemporary art practice began with CCA7 or the people it imported, like Peter Doig or Chris Ofili, when it really began with the dialogues of the early 1980s around the work of people like internationally renowned Mas man Peter Minshall, conceptual artist and now permaculture practitioner Johnny Stollmeyer, Wendy Nanan, and Francisco Cabral, who came before.

Image: A local mas camp with mas band outfits for sale.

Contemporary art certainly doesn’t fall within the purview of CreativeTT, the government’s creative economy project, strategic and business development’s niche areas: film, fashion and music, nor does it connect to the islands’ intention of projecting Carnival as a tourism attraction. One thing that must be understood is that, whenever it’s not carnival, people in Trinidad are preparing for carnival. Businesses plan their year around it and there is a whole industry around the commissioning of costumes for local and international carnivals. From Toronto, to NY or London, Caribbean carnival is global. Though a lot of the money in the local art market has always flowed towards traditional and established art forms such as painting, the National Museum and Art Gallery of Trinidad and Tobago remains dysfunctional and underfunded. When I visited, the supposedly climate controlled room with paintings by Michel-Jean Cazabon, a famous XIX century painter, was decidedly humid and smelly. Exhibition spaces in the city consist of AY, Y Gallery, Medulla Art Gallery and other frame shops. A particular one is the aptly named The Frame Shop A SPACE INNA SPACE, where owner and curator Ashraph delighted me by showing some small paintings by the late intuitive artist Embah. Ashraph has been curating a series of Carnival-themed exhibitions, showing mostly paintings depicting bats, blue devils, sailors, amongst other carnival characters. As far as art spaces go, only AY is strictly non commercial and others, like the music and art venue Big Black Box, or even the members-only Art Society of Trinidad and Tobago are actually for rent. There is a questioning of “who are we talking to?” amongst contemporary artists that AY seeks to address by creating a space of dialogue within the local scene that also provides for continued exchange with international artists and curators at a more human scale.

Image: Artists Luis Vázquez Laroche and Nikolai Noel.

Image: Nikolai Noel, White room (2017), as installed at Alice Yard.

During my stay, I was witness to one such moment: in the first in a series of one day shows at Alice Yard, Nikolai Noel showed and documented two time-based pieces in front of a small audience. White room is an installation consisting of 4 hot plates and 4 pots filled with water and brown sugar, which made the room fill up with vapor. The smell of burnt sweetness seeped out of the room and into the yard. The piece evokes Trinidad's plantation history, the slave trade and the indentured servitude created to sustain the cocoa and sugar farms after emancipation. The black, burnt remnants of the sugar are more reminiscent of the country's current economy; sugar turned into oil. In any case, history stinks and stepping into the room is a dizzying experience. The second piece, titled Invisible Rope, consisted of a found shoe and a single lit white candle. "Whenever someone dies, people light candles in the street to guide the spirits away from their home," he explained. Lost footwear reminds us of the body that once inhabited it, making both pieces feel pretty phantasmagoric. The ideal spatial conditions to show the whole series of works he has worked on would be different, but this will do for now. What Noel wants is to socialize the work and establish a dialogue with others. "In more temperate climates this is more normal, but in the tropics ventilation is the priority,” he said about the vapor in the room, but there’s a metaphor there somewhere as well.

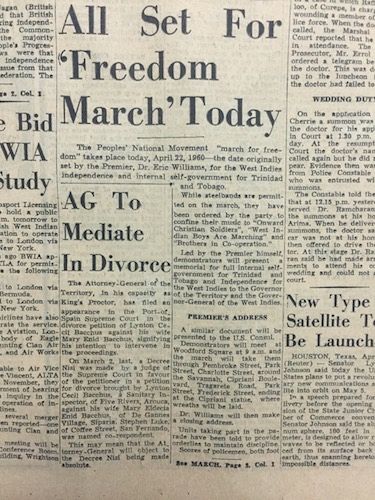

Image: TT Guardian article from April 22, 1960

My main objective in Port of Spain had been to explore Chaguaramas and I prepared by researching the National Archives for news about the protests led by Dr. Eric Williams in the 1960s and the run up to independence. Williams was one of the most ardent opponents of US military presence, considering it central to decolonization. He led the March on Chaguaramas on April 22, 1960 demanding the land back and even burned the Constitution, causing a media backlash from conservative outlets such as The Trinidad Guardian newspaper. I went to Chaguaramas twice, the first time being with Che Lovelace, an artist whom a collector friend from Puerto Rico put me in contact with. Lovelace is the son of famed writer Earl Lovelace, an avid surfer who still competes, and one of the artists who had studio space at CCA7. Now, however, his studio in located in a house formerly used by Navy officers. There is no art program running out of Chaguaramas (although Peter Minshall’s mas camp is also in Chaguaramas) and I hesitate to ask exactly how he was able to rent this space. His recent paintings are on paperboard, a material he started working with 10 years ago, but still feels like he hasn't tapped into its full potential yet. He uses it for compositions and easier transport, as they remain flat and can be shipped easily. The material is acid free and also used for book binding so he can also cut into it and layer it or use it in more potentially sculptural ways. Che incorporates performance, video and photography into his painting process, using himself or others as models while experimenting with form, body and movement in front of the works. All this, however, is done as part of the private process and not in public. A 2014 untitled performance at a NY conference remains his only public piece: a 4-minute interaction between his body, a single steel drum and a wooden panel. Drawing from modern dance, his experience with carnival, and his affinity for surfing, the piece evokes both steel pan drums and oil as representatives of T&T identity. The piece shows the ways in which he understands movement and composition whenever he stood still.

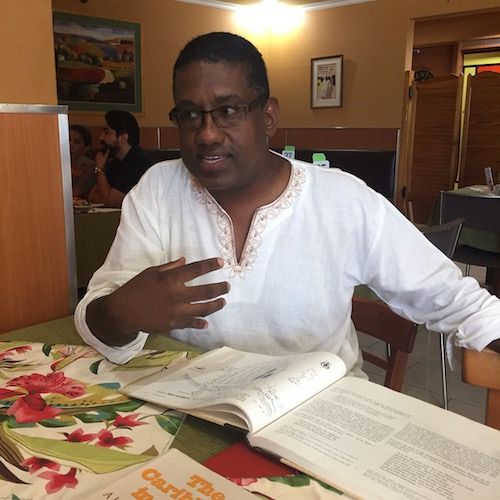

Image: Tour guide Jalaludin Khan with a display of books of Trinbagonian and Caribbean history.

For a more historical visit, Milne set me up with Jalaludin Khan, an artist who also happens to be a hiker, tour guide, environmentalist and, in a perfect turn of events, used to work in the Chaguaramas Development Authority (CDA). Khan sent me a lot of information about Trinbagonian history in an email that included the phrase “constructed visual views of Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago can be reviewed from earliest historical time to contemporary time” - from the Kalinago, to the Santa Rosa Carib Community in Arima, films set in Trinidad, postcards, posters as well as numerous articles and scholarly essays. Needless to say, I’m still combing through all the information he amassed for me and I couldn’t possibly do it justice here. One thing I was there to do was experience the place, and that we did. Milne, Khan and I hopped into her car and spent a day driving around and discussing the neighborhoods of Woodbrook, St. James, Carenage and finally, the former occupied lands of Chaguaramas. On our way there, we passed by fancy event venues, marinas, a water park, people blasting soca music and bars lining the few blocks leading up to the old entrance to the Navy base. Purely out of morbid curiosity, we stopped at the Chaquacabana Resort and Beach Club, which overlooked an industrial port. Barely a year old, the members-only beach club is devoid of any stores and was empty on a Sunday, except for one couple and some employees cleaning up after a party the previous night. The shoddy construction work is evident, with chunks falling off the façade and doors that are too small for the wall opening. Between half finished and future ruin, the resort across the road was set to open a month later, in October of last year. The popularity of all-inclusive parties and carnival make this kind of venue a mostly local affair, and the hotel rooms might be more convenient as after party housing for wealthy Trinidadians than foreign tourists who prefer Tobago's beaches.

Image: View of the Chaquacabana Resort and Beach Club’s villas in Chaguaramas.

There are several businesses that have been allowed to operate through the CDA, but land use zoning is not completely agreed upon in practice and some families still lay claim to the land. Even though, according to government statements, CDA’s mission is “to be the premier provider of the ultimate customer experience in a world-class, ecotourism destination, business and entertainment centre,” its website is currently offline as of January 2018. There are various former hotels inside Chaguaramas, including a US Navy office building that was turned into the Chaguaramas Hotel and Convention Centre, which famously hosted the birth of CARICOM in 1973 and the 1999 Miss Universe pageant. What has happened with that property is emblematic of the business as usual development schemes around tourism in the island. In 2014, it was leased for $30 million TT to an unnamed local investor, yet by 2016 the CDA was already trying to reclaim the property at no cost to the government. According to newspaper reports, the investor only paid about a third of the money and the business was never economically viable, having gone through periods of renovation, upgrading and perpetual deterioration. It was still abandoned when we visited. Ironically, the Trinidad & Tobago Hospitality and Tourism Institute, a school, is also based in Chaguaramas.

Image: Jalaludin Khan and Alicia Milne looking for hidden bunkers.

Image: Jalaludin Khan clears the way to a bunker.

Image: View inside the bunker.

A little farther along, we snuck into a building that was turned into a makeshift skate park and, if we go by the amount of graffiti and beer bottles, a pretty cool hangout spot. Khan led us on car and foot through various other sites that have been converted for sport and entertainment, used overwhelmingly by Trinbagonians themselves. Some of the sights are really fascinating: World War II bunkers hidden by the dense forest, and the “bamboo cathedral,” a pathway that eventually leads to the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System station uphill, where we also saw monkeys. To our amusement, Khan recounted a local folk tale about La Diablesse, a seemingly beautiful woman who leads men into the forrest (or an apology for infidelity), which led me to remember the wonderful watercolors by Alfredo Codallo, a highlight of the National Museum and Art Gallery collection. Milne and I wrapped up our day by taking a dip in the once off-limits Macqueripe Beach. At one point a drunk guy came up to us and, assuming we were Venezuelan because of our light skin tone, started harassing us into speaking Spanish until we convinced him to leave us alone. Trinidad is (I would learn during my time there) an important stopover spot for drug cartels and human trafficking due to its proximity to South America, and a conduit to the US and Europe. I was actually singled out and searched twice at the airport when I flew back home through Miami. The explosive political situation in Venezuela has also caused a recent influx of immigrants, something that is replicated in Panama as well. Trinidad is an incredibly multi-ethnic place, and Milne’s work often contemplates issues of belonging, incorporating how she−a light skinned, red haired woman−is perceived in the Caribbean through video, installations and objects, particularly with ceramics. A recent residency in China has influenced her production due to the availability and cheapness of materials there, in a curious parallel to economic shifts in the region, as the influx of Chinese imports and investment drive more Caribbean countries into China’s sphere of economic influence.

Image: DIY skatepark in Chaguaramas.

Image: The so-called bamboo cathedral in Chaguaramas.

In Puerto Rico, former military bases in Vieques and Culebra have been declared natural reserves and decontamination has been practically non-existent since the conversion to civilian use. There, “natural reserve” is often code for a no-go zone. In the former Roosevelt Roads Naval Station there is an airport, and its Development Authority has authorized some small businesses to bird watching tours, and rent or sell sporting goods, but little else has been developed or reverted to the people of Puerto Rico. Schools, houses and even a cinema sit empty and derelict while successive governments plan such disparate and frankly offensive schemes like building a luxury residential area and yacht marina in one of the poorest regions in the country, or establishing a Virgin Galactic launch site. The most recent proposal to turn it into the new Amazon headquarters was actually submitted to the internet giant last year, a mere weeks after Hurricane Maria made landfall, and generated widespread mockery online. My point is: the last thing the Puerto Rican government has thought of is reverting to land to the people who were evicted or establishing any kind of project that would be more community driven. For now, Chaguaramas is open to the public to be enjoyed but land use issues persist. Land legally assigned for farming is being used to run a “safari” business with imported animals, in a country that, like most in the Caribbean, imports most of its food supply. Natural reserve land is being leased for marinas, restaurants and future shopping malls, all under the guise of boosting tourism. The future of Chaguaramas will depend on the comings and goings of conflicting political parties that chip away at the integrity of the territory, and no masterplan that can be easily identified.

Image: View of Macqueripe Bay Beach.

Though originally focused on US militarism, I came away from conversation with Cozier much more interested in Caribbean intellectuals who sought, theorized and acted upon ideas that reimagined Caribbean sovereignty in the postcolonial era; men like C.L.R. James, Lloyd Best and the Tapia House Movement. The Lloyd Best Institute of the West Indies in Tunapuna was a good place to converse with Cozier while we searched for interesting articles in Best’s Trinidad & Tobago Review. Cozier had been a friend of Best’s and wrote biting art criticism for the publication in the 90s, specifically pointing out the need to break out of the inherited ways of seeing the Caribbean self and even asking -I’m paraphrasing- why artists still painted the same goddamn colonial scenes and houses.

Image: A Tapia House poster at the Lloyd Best Institute, Tunapuna.

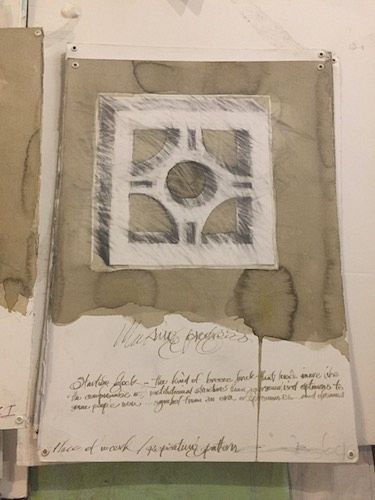

A cancelled flight post Hurricane Irma made me stay an extra day in Trinidad, and I was finally able to visit Cozier’s house and studio. Going through his body of work in person for the first time, he explained his longstanding interest in breeze blocks -a common sight in Caribbean construction- as metaphors for institutional compromise. The piece ”Gas Men" show them swinging petrol nozzles around against a generic horizon, and "Globe" has them in Spaghetti Western stand off poses. In his series Entanglements, the bodies of industrial Caribbean creepy crawlers are composed with the artist's thoughts and scribbles on paper. HOME, a recent project in Boston, features a sculpture of a red staircase and a collaboration with notable Trinidadian fete sign painter Bruce Cayonne, and Bostonian via Trinidad collective Intelligent Mischief, about what makes a place feel like home, while addressing issues of gentrification, working with Caribbean communities in the city. The following day, suitcase in tow, Alex Kelly showed me the studio space he shares at Granderson Lab. His work seeks to examine social circumstances that have defined the present realities of his country, particularly through drawing, objects and installations. Totem (2016), which consists of 5 stacked steel drums and a wooden pallet on top placed on an empty lot as part of the Out of Place series, is a particularly effective piece that references Trinidad’s import/export sector. Before heading out to the airport, he acquiesced to my request of visiting the Hilton Hotel atop the hills, and I was finally able to see the savannah, the city and the sea beyond.

Image: A 2004 Christopher Cozier piece that reads: “Starting blocks…The kind of breeze block that looks more like the compromise of institutional structures than the personalized options to some people now…symbol of an era of promises and dreams.”

Most or all of the countries I would visit in the next few months have had histories marked by the effects of the plantation economies established by colonization, slavery and indentured servitude, military occupation, independence struggles, industrialization by invitation economic strategies, high dependency on imports, offshore banking and tourism. There have been many independence-affirming moments in Trinidad’s history, from the decolonizing movement, and the experiment of regional integration through the West Indies Federation, to actual independence in 1962, along with the expulsion of the US military from the island. In the following decades, a new generation of artists would reassert their claim to a different way of making art that didn’t follow the usual dogma of landscapes, and urban scenes of colonial style houses, though they still persist and sell a lot more than anything else. The new independence movement might be a shift away from the dependence on oil, but if the turn is towards a wholesale investment in tourism, it is doubtful that Trinidad & Tobago will come out as the only country in the Caribbean to have tourism that is not exploitative. Some of the artists I met are wrestling, like a lot of us, with the reality of climate change and the culture of consumption and corruption driven by oil money.

One night, walking back from dinner and a beer around the corner from the yard, Kriston Chen mentioned a climate change poster he had seen online which resonated with Trinidad: “Just because the world runs on oil doesn’t mean oilmen should run the world,” it said. Tourism either.

Image: Blessed Indies (2017), a Nikolai Noel painting.