You may recall from the introduction to this research project that it was after a studio visit with Andrew Norman Wilson that the term “glitch” first began to consume my thoughts, and it was in regard to his work that many of my initial questions arose. So in this installment, I will focus my inquiry on the work of Wilson, and specifically his project ScanOps (2012).

The title of the series, ScanOps, refers to a particular class of workers employed by Google at their international headquarters in Silicon Valley, who are responsible for the digitization of the world’s books for the media conglomerate’s highly contested and controversial Google Books initiative1. As a one-time contracted employee of the internet giant back in 2007, Wilson became intrigued with this group of workers, specifically because they did not share the same famous perks as other Google employees, and were neither free to comingle with other staff nor discuss the nature of their work. Employing a system of color-coded badges (think Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World), Google has gone to great lengths to keep this population of workers segregated and relatively anonymous within the larger organizational structure. In fact, Wilson was fired from his position for his attempts to interview and film these workers, an affair which he documented in his 2011 video Workers Leaving the Googleplex.

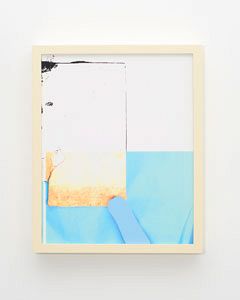

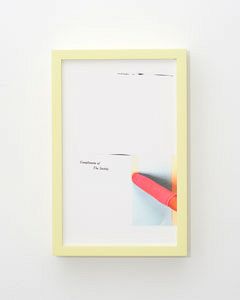

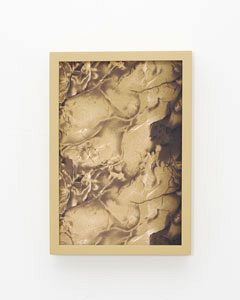

Andrew Norman Wilson. Mechanick dyalling: teaching any man, to draw a true sun-dyal on any given plane, however scituated – 60, 2012;

Andrew Norman Wilson. Motor Age – 7, 2012. Photos courtesy of the artist.

With his dismissal, one would think that Wilson’s investigation into the ScanOps workers would have come to a halt, but after a friend directed him to Krissy Wilson’s tumblr page, The Art of Google Books, a new investigatory approach presented itself to him2. What Krissy Wilson had begun to document and compile were anomalies culled from Google Book scans, in which glitches in the scanning and editing system were revealed and catalogued along with the rest of the pages of the book or manuscript. Most curious of all, however, these glitches sometimes revealed the hand of the actual worker in the midst of preparing or moving on to a new scan. So it was in this way that Andrew Norman Wilson was able to reconnect with the people he once worked in the proximity of, but was never able to fully engage. Still removed, he now directs his searches for glitches in Google Book scans in a very thoughtful and calculated way, looking for signs of the very workers whose presence the system goes to great lengths to obfuscate, that is, the very evidence of this system at work. A key point not to overlook here, and as Wilson has himself pointed out, “the workers compose part of the photographic apparatus, which, conceived in a broad sense includes not only the machinery, but the social systems within which photography operates.”3 This adds a more discrete dimension to the rather generalized “system” that I have been referring to, where the discussion doesn’t merely concern the technological or mechanical processes for production, but also the social, political, and cultural systems that have produced such processes as well as the different classes of workers that are involved in such. This understanding of the glitch may differentiate Wilson from many other glitch artists, and when I questioned him on his relationship to the glitch movement, Wilson explained to me:

I appreciate the movement but maintain little to no participation at the moment. I’m not interested in or experienced with the coding, hacking, and technical manipulation that the movement’s makers employ. The focus in the movement hones in very closely on the particular technologies they engage and the effects they can produce. While I’m always interested in and attentive to technical specificity, I try to fold in a broader range of concerns.4

In fact, there does seem to be a difference between Wilson’s concerns and those of the glitch artists I have spoken with. While they all find meaning and significance in glitches, what they do with them beyond the specificity of the digital realm may differ. Norman’s interest is clearly in how his practice can begin to ravel and unravel glitches as part of larger histories. In a recent email exchange, I asked Wilson about his emphasis on materiality and his rejection of the idea that digital artworks, net art and the like, are immaterial in nature. His response elucidated a number of key elements of the ScanOps project, as he explained:

The ScanOps project is most effective for me as image-sculptures, in a book, or presented as parts of a performance. They’re both indexical, and medium-specific. Their processes, digital distortions, and material supports are folded within them. The fingers and software distortions that obscure the “pure information” in the books complicate Google’s technocratic proposals for a utopia of universally accessible knowledge. What emerges is an argument for the inseparability of matter and meaning, fusing a discussion of knowledge with ontological, ethical, and aesthetic issues… What I’m after are traces of materiality, and then in the art objects leaving more traces of materiality through printing, painting, texture, shape, size, etc.5

Andrew Norman Wilson, Simon Newcomb – 10, 2012. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Andrew Norman Wilson, The Encyclopedia Americana – 879, 2012. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This interest in object-making, and the insistence upon the materiality of digital outputs allows Wilson to further connect his project with the history of photography in general—Wilson has cited such photographers as Elad Lassry and Walead Beshty,6 along with Dorothea Lange, Jacob Riis, and Lewis Hine as influential to his work7 —immediately expanding the parameters of the conversation to engage with a greater historical narrative. On the other hand, the glitch community seems to be invested in articulating how the digital realm and digital technologies represent an unprecedented shift in the flow of information and access to said information in the world today, and this is coupled with an investment in exposing the new systematic forms of governance and control that have been created to manage this new development. In short, this analysis serves to begin to uncover the different intentions, desires and concerns that are at play in the articulation of a community of people/artists, and the reasons for which those people/artists self-select and identify (or not) with any particular community.

The term “glitch art” may refer to a distinct genre of artistic production—albeit one with a wide array of methodologies and outputs—and within which practitioners are self-selecting/identifying members of a broader community which includes artists and other types of cultural producers alike. It is also clearly evident that glitch art, despite its unique particularities, intersects with numerous other art historical movements and shares a long-standing interest with them in the productive, generative potential of errors, mistakes, and corruptive interventions.8 In this light, it would seem that glitch art—more loosely defined and loosely bound—underscores an artistic strategy that serves multiple interests, with the tailoring of those interests just as informative as the actual phenomenon itself.

Footnotes:

1. For a good overview of the ensuing legal battle: Carlos Osario, “Google Book Search,” New York Times online, March 24, 2011, http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/business/companies/google_inc/google_book_search/index.html.

2. Andrew Norman Wilson, personal communication with the author, August 8, 2012.

3. Louis Doulas, “Art from Outside the Googleplex: An Interview with Andrew Norman Wilson,” Rhizome.org (New York), May 14, 2012, http://rhizome.org/editorial/2012/may/14/conversation-andrew-norman-wilson/.

4. Andrew Norman Wilson, personal communication with the author, August 8, 2012.

5. Andrew Norman Wilson, personal communication with the author, August 8, 2012.

6. Louis Doulas, “Art from Outside the Googleplex: An Interview with Andrew Norman Wilson,” Rhizome.org (New York), May 14, 2012, http://rhizome.org/editorial/2012/may/14/conversation-andrew-norman-wilson/.

7. Andrew Norman Wilson, personal communication with the author, August 8, 2012.

8. Nick Briz, “Glitch Art Historie[s] / contextualizing glitch art—a perpetual beta,” in GLI.TC/H 20111: READER[R0R], Tokyo: Unsorted Books, 2011, pp. 53–58.