I. The Dreamwork

I recall with clarity that moment, a few months back, when it seemed I had finally lost the plot. On April 3rd, throughout dinner and during my cab ride home, I had been receiving text messages from a friend who was attending a highly anticipated auction that evening at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong, The Ullens Collection: The Nascence of Avant-Garde China.1 Among the sale’s 106 works were many historically significant paintings made during the decade between 1985 and 1995, including early efforts by artists who later became the most well-known and commercially successful of their generation, such as Cai Guo-Qiang, Liu Xiaodong, Wang Guangyi, Yu Hong, Zeng Fanzhi and Zhang Xiaogang. According to a statement issued on behalf of collector Guy Ullens, liquidating his collection of Chinese art was a way “to give these works back to the country.”2

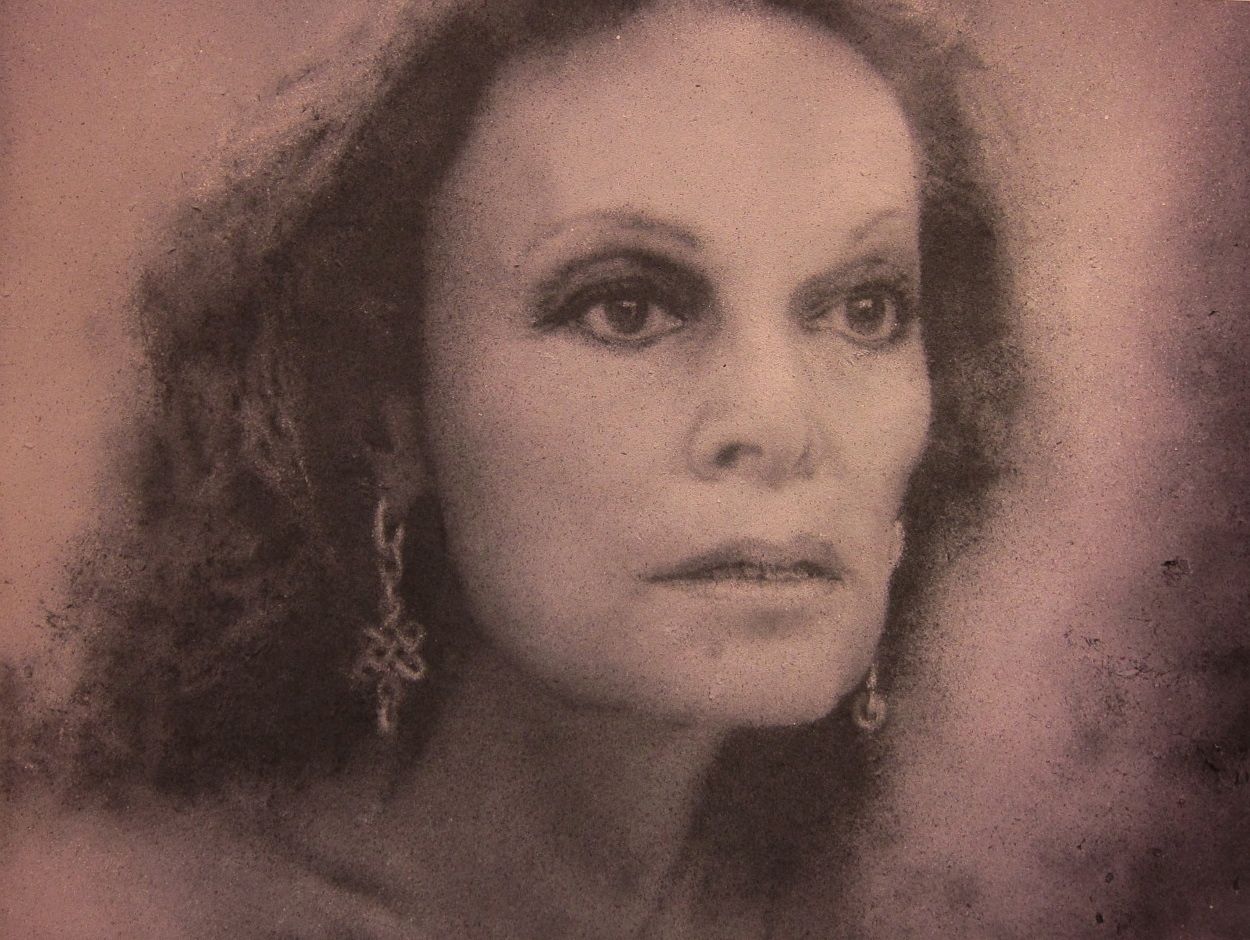

Zhang Xiaogang. Forever Lasting Love, 1988. Oil on canvas. Triptych, each section approx. 49 x 39 inches.

“Works circulate,” one gallerist said to me earlier in the week, when I suggested that perhaps another way to “give back” to China might be to donate works to a Chinese museum, giving the public a chance to consider their own art history. Now my phone was buzzing with news of the bids: “Zhang Peili glove painting up to 20 mill HKD” one message read. “#808 now at 42 mill HK and rising.” Lot no. 808 was Zhang Xiaogang’s Forever Lasting Love, a rare 1988 triptych depicting a sprawling story of life, death and regeneration drawn from the artist’s interest in mysticism and Eastern philosophy. Like some of the other works in the auction, Forever Lasting Love had been shown in the 1989 China / Avant-Garde exhibition at the National Art Museum of China, the culmination of the radical artistic experimentation that had swept through China during the latter half of the ‘80s. Now, under the bright lights of a crowded auction hall in Hong Kong, the painting’s price was soaring to astronomical heights. Forever Lasting Love sold that night for HK $79 million (US $10 million), the highest price ever paid at auction for a piece of contemporary Chinese art.

Museum visitors in front of signage announcing the China/Avant-Garde exhibition, held at the National Art Museum of China (formerly called the National Art Gallery) from Feb 5 - 19, 1989. Photo: Wang Youshen.

Results from the final lots were still coming in on my cell phone when I sat down to check my email. That’s when I discovered that artist Ai Weiwei and members of his staff had been detained by authorities at the Beijing airport, and their whereabouts remained unknown. It was the latest in a series of arrests, detentions and disappearances that began in mid-February, perhaps in response to growing fears that the protests sweeping through the Arab World could inspire similar events in China. “The current crackdown on activists in China is the most severe in a decade,” Sophie Richardson, Asia advocacy director at Human Rights Watch, had warned on March 31st. “Governments concerned with human rights in China should not continue with ‘business as usual’ while peaceful critics are being locked up one by one.”3 Now China’s most internationally visible artist (and outspoken critic) was among the many who were missing.

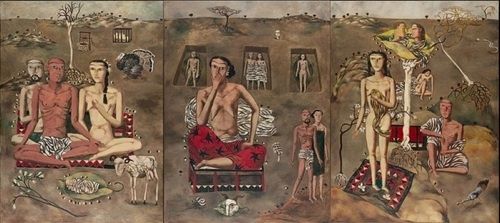

Also in my inbox: News of the opening, at Pace Beijing, of the exhibition Diane von Furstenburg: Journey of a Dress, a large-scale, immersive brand-building exercise featuring a selection of brightly-patterned frocks displayed alongside hundreds of images of the designer herself, a veritable stalker’s gallery ranging from Warhol portraits to framed news clippings. A few days before, von Furstenberg had thrown her “Red Ball,” a party held in artist Zhang Huan’s Shanghai studio. According to one report that had been forwarded to me via email, the gala’s “Alice-in-Wonderland effect” was created by “a sumptuous fantasy of gigantic Buddhas and thumping music and delicately painted Chinese paper lanterns outlining the ‘DVF’ logo.” “Twelve years ago I went to New York and found my American Dream,” Zhang Huan told the crowd. “And today, Diane has come to this humble place to realize her Chinese dream.”4 In fact, it was precisely the symmetry of these two dreams that was now troubling me.

Portrait of Diane von Furstenberg by Zhang Huan (detail). Incense ash on canvas.

II. “The future is already here…”

Nearly six years ago, I came to Beijing in search of a better understanding of the art being produced here; I was curious, too, about local critical positions and systems of display. Now it was time to climb out of the dream-work and focus again on artistic practices, particularly the surprising approaches and formal innovations of younger artists whose work was just emerging. It was time to revisit the recent or lesser-known artistic output of the most established contemporary artists, who, more often than not, had progressed beyond the iconic images that they are so strongly identified with. It was time to look at the proliferation of artist-initiated or otherwise “alternative” platforms for curatorial experimentation and community engagement that were taking place outside of commercial galleries and museums. It was time to reconnect with the debates that were developing among local curators and art historians, including crucial questions about Chinese art’s place in relation to notions of modernity and contemporaneity.

Over the next two months, this DISPATCH will evolve to include my research notes, observations, and interviews, accompanied by related images. It will also feature a Reading Room, where I will post links to articles and other materials that I hope will be informative, supplemented by my own commentary. It is my ambition to provide multiple viewpoints and artistic, curatorial and art historical perspectives that are relevant locally, but not yet widely visible or understood outside of China.

Footnotes

1 Full disclosure: As indicated above, I worked as a curator at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing from 2007 to 2009.

2 “Ullens Collection and UCCA Statement” (February 15, 2011). Posted on The Shanghai Eye. Retrieved June 20, 2011 here.

3 “China: Arrests, Disappearances Require International Response” (March 31, 2011). Posted on Human Rights Watch. Retrieved June 20, 2011 here.

4 Melinda Liu. “The East is Red: Diane von Furstenberg’s High-Fashion China Bash” (March 31, 2011). Posted on The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 20, 2011 here.