In the late 1960s the New York art world was, famously, an exciting place to be. New mediums such as performance and video art were developing, and sculpture was quickly expanding in many different directions. Experimental abstract painting that pressed the medium to its limits was an important part of the moment, and this exhibition recaptures its liveliness and urgency. All of this was happening during a politically and socially tumultuous time in the United States, a time when the art world, too, was changing under the impact of the civil rights struggle, student and anti-war activism, and the beginnings of feminism. Painting is the one element usually left out of this complex narrative, remembered only as a regressive foil to the various new mediums. But this version of the story greatly oversimplifies the situation, effacing painting that earned a place among the most experimental work of the moment, very much in sympathy with the era’s radical aesthetics and politics.

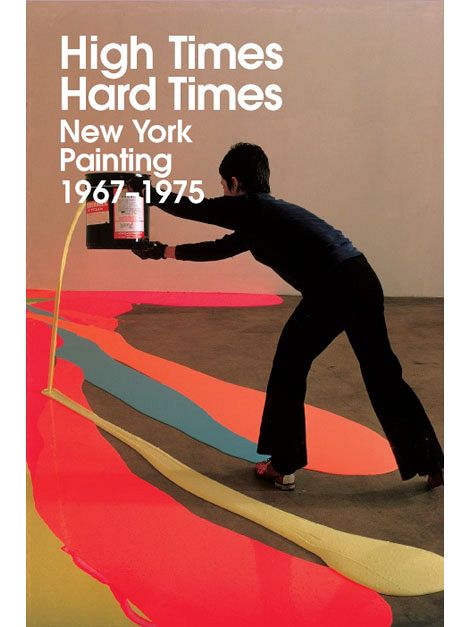

This turbulent period is captured in High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967-1975, an exhibition that brings together approximately forty works by thirty-eight artists living and working in New York from 1967 to 1975. The exhibition is divided into five groups, with categories that are at once formal and chronological. Beginning with a moment of exuberant “flower power” abstraction circa 1968, these paintings are brightly colored and wildly expressive. In the central sections of the exhibition, painting comes off the wall and incorporates installation, performance, and video, embracing new artistic mediums as well as the spirit of liberation moving through the city. At the very end of the exhibition, these innovations are reincorporated into the more conventional medium of painting proper. Like the political legacy of “the 60s,” these experiments never disappeared completely, but have continued to influence the way artists work and think about painting.

The artists in this exhibition range from well-known figures like Yayoi Kusama, Blinky Palermo, and Richard Tuttle, to now less-familiar names such as Dan Christensen, Harmony Hammond, Ree Morton, and Alan Shields, who were extremely important at the time, as well as influential for other artists. High Times, Hard Times recovers the thrilling innovations of the time, as well as their social context. Half of the included artists are women, and many are African-American (including Al Loving, Joe Overstreet, Howardena Pindell, and Jack Whitten); these identities are not incidental but essential to grasping the possibilities of the period. (And perhaps part of the reason this painting has been left out of the history books; subsequent painting revivals have been adamantly male--as Joan Snyder complained about macho neo-expressionism’s sudden revival of painting, “It wasn’t ‘neo’ to us.”) Artists from other countries who lived temporarily in New York (Yayoi Kusama, Blinky Palermo, Cesar Paternosto, and Franz Erhard Walther) similarly either were not recognized at the time or, conversely, were afterwards excluded from paintings’ canonical history.

The works in the first group dating from the late 1960s are large, rectangular, stretched canvases hung on the wall—a format based on conventions challenged later in this exhibition--that elicit the mood of euphoria and optimism so prevalent in the late sixties. This feeling is most clearly evoked by the psychedelic colors and optical effects of the works by Dan Christensen, Mary Corse, Ralph Humphrey, and Kenneth Showell. In the second grouping, artists begin to take painting apart. These paintings are often super-thin or made of soft unsupported cloth (Richard Tuttle, Louise Fishman, Howardena Pindell, Mary Heilmann) and some even come off the wall into the room (Al Loving, Lee Lozano), sit on the floor (Lynda Benglis, Harmony Hammond), or are suspended from the ceiling (Manny Farber, Alan Shields). The wild array of structures and formats take liberties with the medium of painting in ways that challenge its history and expand its future. These works can be hung together more tightly in the exhibition space, as they were at the time, stressing the energy of the artists and their efforts. Installation and performance are emphasized in the third selection of works, stretching the elastic definition of painting even further, as painters experience the pressure and possibility of new mediums such as installation and performance. The artists use their bodies and the space around the physical projects, incorporating the viewer into the environment of the work. These installations include large floor pieces (Mel Bochner, Dorothea Rockburne) that peel off the wall, spread out and breathe into the room. The performance pieces will be documented by photographs or video (Carolee Schneemann, Yayoi Kusama, Franz Erhard Walther), and in some cases the original works will be recreated according to the artist’s instructions. This is painting pushed to its limits; these works have an intensity and expansiveness that springs from a willingness to doubt fundamentally what a painting is. The work by Bochner is owned by MoMA, but has never been exhibited at the museum; Schneemann, although a well-known artist, will be represented by a painting performance on video that has never been shown. Much of this art will be surprising even to scholars and critics of the period, and should elicit reappraisals of some of the lesser-known painters in this exhibition, as well as of the artists more often associated with other mediums and practices.

Film and video exerted their own pull in the early seventies; many if not most avant-garde artists experimented with these new mediums. The fourth group of works includes paintings that reflect this influence. Using unusual techniques including spraying, iridescence and visual interference, the surfaces of these works suggest filmic effects such as speed, flicker, and distortion (Roy Colmer, Michael Venezia, Jack Whitten). Many of these painters also used film and video directly, and this section includes film and video works (Roy Colmer, Lynda Benglis) that connect with the paintings through their sense of color and movement.

No artistic culture could indefinitely sustain either the total possibility or the intense doubt of the early 1970s. By the mid-seventies, painters had returned to more traditional stretched-canvas formats, but many brought the innovations of deconstruction, performance and installation with them. Some of the work in this final group carries with it a frankly elegiac mood, marking the end of the previous moment of limitless horizons. Other paintings are infused with bold color (Mary Heilmann), a celebration of paint’s physical properties (Guy Goodwin), and even imagery (Pat Steir). While the exhibition’s ending represents a “return” to more traditional forms of painting, it captures not only the discoveries of earlier experiments, but also the tremendous opening-up of painting in the 1970s. High Times, Hard Times recovers a missing history, providing a broad but detailed context for the monographic surveys currently and soon to be circulating through major American museums, featuring artists such as Lee Lozano, Manny Farber, Mary Heilmann, and Richard Tuttle. The exhibition also resonates with contemporary conditions; many young artists ask, as Al Loving and Richard Tuttle both did in 1968, how painting can matter in a turbulent world. The paintings in this exhibition connect our present moment to a rich and exciting past that continues to resonate today.

We thank David Reed for serving as curatorial advisor on this exhibition.