To read this essay on ARTnet, click here.

If Museums in the US Want to Be More Inclusive, They First Have to Recognize—and Unlearn—Old Habits and Biases

Developing new kinds of cultural institutions also means developing new vocabularies.

Renaud Proch [Published June 25, 2020]

On March 23, critic and curator Maurice Berger died of complications related to the coronavirus. The following week was an opportunity to re-read his 1990 essay, “Are Art Museums Racist?”

At the time, less than three weeks into New York City’s stay-at-home order, we at Independent Curators International (ICI) were seeking a global understanding of the impact of the pandemic by reaching out to recent and current collaborators from all 50 US states, Washington, DC, Puerto Rico, and 70 countries around the world. From the 1,500 curators and artists we contacted, we compiled scores of impressions coalescing around a small number of consistent concerns.

We learned, for example, that many independent curators saw a number of core issues increasingly shaping their thinking and practice—issues which, far from being new, became louder and more urgent amid the pandemic. They included labor conditions, migration, xenophobia, and racism.

Change begins with awareness of the problem, they say. But Berger found that museums were broadly unable to meaningfully present works by African American artists 30 years ago. And just five years ago, a Mellon Foundation study of the US museum field found that only 16 percent of specialized and leadership positions (such as curators, conservators, educators, and directors) were held by people of color.

Awareness of systemic over-representation of whiteness in US cultural institutions—that is to say, awareness of systemic racism—has grown since the Mellon report, and a number of subsequent studies have shed even more light on the problem. Among them, the CreateNYC Culture Plan, issued by New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs in 2017, offered a damning verdict on one corner of the cultural field: “The whitest job in arts and culture? Curator.”

With a new awareness of the issue, focused on the curatorial field and backed by metrics, many arts organizations across the country took steps to address a “diversity problem” in their midst. Their efforts were backed by the leadership (and power of the purse) of several large foundations, such as Mellon and the Ford foundations, and by local governmental bodies, including New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs.

Across the field, an emphasis took hold on the need to diversify staff and boards, so that they may be more representative of their communities, or the country’s demographics. At several museums, priorities in hiring changed in order to diversify the curatorial ranks. Other institutions sought to address an educational system that has kept people of color out of the academic training pipeline for curators, and to invest in the future through scholarships and fellowship opportunities that will in time diversify applicants pools.

These have been important steps in the right direction. But is it enough?

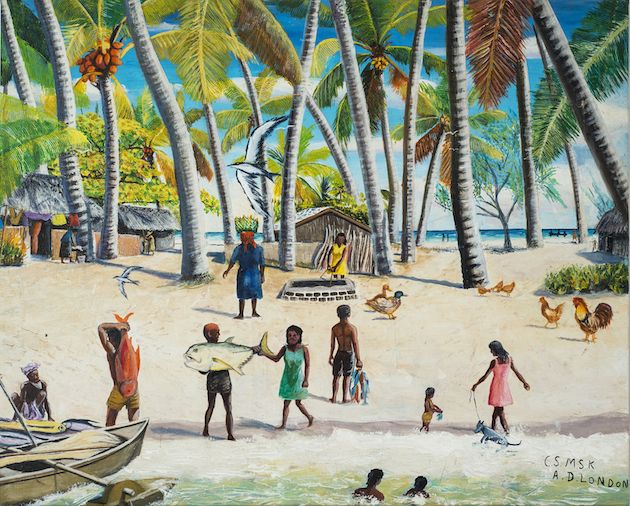

ICI’s Curatorial Intensive at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, January 2015. Photo: ICI

This is a question that has occupied us at ICI for most of the last decade, and the question of over-representation in the field has been core to our programs. Our approaches have evolved over time, and are now increasingly driven by the perspectives of curators within our own networks: out of the 136 US-based professionals who participated in ICI’s Curatorial Intensive (our professional development program for emerging curators) since 2010, less than 40 percent identify as white. But how could the diversity of our network be reconciled with the realities of a field that remained overwhelmingly white? What were the obstacles to change?

There are many models of social change, and one that I find particularly useful comes from 12-step recovery programs, the Three A’s: Awareness, Acceptance, and Action. What is particularly useful about this three-part method is the suggestion that for change to be meaningful, we cannot simply rush to action to remedy a problem we have been made aware of. We need to accept our own relationship to the problem.

Let’s begin with curatorial work, which is profoundly discriminatory by nature. Curators decide whether to include or exclude artists and artworks from exhibitions and publications, and from art history and collective memory. It’s worth considering and accepting this part of the role.

In doing so, we understand that the power to make these decisions is bestowed upon curators by their peers, whose respect they earn. Following this logic, we begin to see a feudal system, where curators are recognized as the guardians of the archive, the scribes of art history’s first draft, the arbiters of taste, only as long as their work validates the field that empowered them. And in the US, the field that empowers curators for as long as they validate it—the world behind the gatekeepers—is dominated by Euro-American art history and ideology. It is a world buoyed by 20th-century nationalist pride; centered on museums rooted in the 19th century and the colonial era; that claims a genealogy going back to the white marbles of Ancient Greece, almost halfway across the world.

The curatorial rank and file should reflect the country we live in, and so should the field that validates them. Beyond reviewing hiring policies, institutions must decide whether they are ready to make space for another narrative, and to value and fully empower different forms of knowledge. Are they ready to shift their relationships to the white art history embodied in their collections by ceding its assumed dominance?

Are institutions ready to shift their high-entrance-fee admissions policies that disproportionately exclude people of color? Indeed, as museums are considering a near-future with limited attendance due to COVID-19, and a resulting decrease in admission income, will they take up the opportunity to reinvent themselves as truly inclusive civic institutions with free admission? At ICI, we have learned from the experience of colleagues in art spaces that adopted a free admission policy, as they described an immediate shift in their audience becoming not only larger, but also more diverse. And a larger more diverse audience in turn came to expect more diverse and representative exhibitions and programs, prompting a reshaping of the curatorial role and who could fill it.

Working internationally, we have also learned to use important tools to better shift our own organization. We learned to rethink our knowledge structures: once we discarded the notion of a curatorial curriculum or an art-historical canon—exclusionary by definition and almost always strengthening the dominance of Euro-American art history—collaboration and horizontal models of knowledge-sharing became our working modes.

We also learned that some of our vocabulary is exclusionary. One of the most potent changes we’ve made was to the working definitions we use. The word “curator” is exclusionary. Redefine it. We adopted a definition of curators as “arts community leaders and organizers,” a term we came to understand with Miranda Lash, curator of contemporary art at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky. The term “contemporary art” is exclusionary too. Redefine it. This was an approach we owe to Shuddhabrata Sengupta of Raqs Media Collective, who suggested that in considering art, we take the largest, most encompassing possible definition.

What we learned from our colleagues around the world and around the country, often outside of the main art centers, we applied to our day-to-day work. Institutions can do the same. One change to the system may not be enough; but coupled with other adjustments across the institutional structure, it can have an exponential impact. With awareness and acceptance, institutions will have a chance not only to diversify their staffs, but also their power structures, their work, their audience, and ultimately their civic mandate.

This has been a guiding principle of ICI’s Curatorial Forum, organized with EXPO Chicago every September since 2016, which convenes 40 US curators to generate conversations about the civic responsibilities of museums, topics of accessibility, regionalism, and race and representation. This fall, we will organize a version of the Forum that will build upon past sessions focused on racial equity and how museums can reach a level of awareness and acceptance from within the institution, together with all their stakeholders.

The task of institutional change isn’t small. However, not far from the museum’s doors, independent curators of diverse ethnic, racial, and socio-economic backgrounds have already been rethinking their relationships to the dominant arts and culture field, its preferred language, canon, and the ideology it promotes. They have developed ways to serve artists first, operate independently of the market, and represent a multiplicity of voices and practices that complicate, rather than consolidate prevailing versions of art history. They are creating more than exhibitions—they are shaping different realities through research, publishing, and organizing.

Many people in this new generation of independent curators have found opportunities to present their work in supportive regional and culturally specific museums, while others have created their own digital and physical spaces and founded and/or led art initiatives and small organizations. In taking charge of creating new models for smaller institutions, they have helped define a more inclusive context for art production and presentation, and a more direct relationship to artists than many of the larger institutions and museums, which are slower to adopt change. While these initiatives are not meant to replace the museum, they contribute to shifting the expectations that the curatorial field and art audiences alike will have of their larger cultural institutions.

It is our hope that, in addition to structural change in arts and cultural institutions, this time will prompt the country’s philanthropic field to more fully support independent curatorial voices through direct research, exhibitions and project grants, and to drastically increase the funding of curator-led arts initiatives and small organizations that have shown to be more resilient, responsive, and committed to racial equity through the crisis.

At this time of national crisis, when so many institutions are closed to the public and struggling to articulate their support of people of color, our belief in the need to empower and sustain an already diverse and dynamic independent curatorial field is only heightened.