Risa Puleo: 2022 Curatorial Research Fellow

Photo credit: Gonzalo Reyes Rodriquez.

Zoe Dobuler: I would love to begin with a bit of context about your involvement with Counterpublic – you were part of a team of curators, each of whom engaged different spaces and the land along Jefferson Avenue, a six-mile continuous stretch that moves through many of St. Louis’s demographics. Your contributions were focused primarily on the area between what is colloquially known as the State Streets Neighborhood and Sugarloaf Mound, the last remaining mound built by Native communities left in the city. I would love to hear how you came to that site – what drew you to it initially, and how did it fit into your broader practice and the wider aims of the exhibition?

Risa Puleo: Counterpublic’s invitation to respond to St. Louis allowed for a serendipitous meeting of many worlds that I was investigating independently of each other. When Counterpublic director James McAnnaly first got in touch, I had been visiting different mound sites throughout the Midwest and Southeast. I was newly teaching Native American art history at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago and imagining what a class about medieval North America could be. There is no medieval art history of the Americas at any college or university that I know of, I think because the discipline is built on European methods that have historically reinforced the terra nullius (meaning blank slate) logic of settler colonialism. Visiting mound sites throughout the Midwest and the South was also a reason to get outside the house and go to places where there weren’t a lot of people during quarantine.

The research into Mississippian Mound Building culture came after two really big shows, probably the shows, at least until Counterpublic, that I’m best known for. Monarchs: Brown and Native Artists in the Path of the Butterfly (2017) aimed to draw out the structural logic that connected NoDAPL protests at Standing Rock and threats to build a border wall. Monarchs brought together brown and Native artists from across the Americas living in the US in a moment when the changeability of settler borders revealed them to be methods to enclose, capture, contain, and manage the lives of people who are Indigenous to the Americas. In Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System (2018), I was thinking about the relationship between the institutions of the museum and the prison, seeing the former as a disciplinary agent, and the latter as a collection of people to show. I applied an abolitionist framework, focusing on artists who leveraged their practices to find strategic pressure points in the system to enact an intervention. I was writing the catalogs for Monarchs and Walls at the same time and also didn't have enough distance to see how they were related.

The way that my curatorial practice works is that one show will have a question and the next show is created as a kind of answer that also generates a new question. I then look for artists who are asking similar questions. The geographic specificity of St. Louis and the mounds were the missing pieces to the unanswered question that connected Monarchs and Walls. Counterpublic offered an opportunity to propose an answer: the prison cannot be abolished until the settled nation that it acts as an extension of is also dismantled.

ZD: I’m curious what you mean by “the geographic specificity of St. Louis” – beyond the geography of the city itself, how did its place within the larger U.S. impact your thinking about the project?

RP: Something I came to understand about St. Louis over the three years that I was working there was how the city developed its identity as the “Gateway to the West:” It was the place from which the majority of U.S. soldiers who were sent West to dispossess and enact mass genocide of Native populations, to open the path for the settlers who followed them, were deployed. In other words, the “Gateway to the West,” from another perspective, is the gateway to dispossession.

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 made St. Louis the frontier of the U.S. But after the U.S. gained jurisdiction of lands that had been Spanish, then Mexican claims, St. Louis became the center of the country and the frontier was pushed further and further west. This shift from the edge to the center of the country made it a launching point for soldiers, settlers, and also ideology: St. Louis is the birthplace of the idea of Manifest Destiny, developed as a propaganda device by Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton.

There is a park named for this Senator at the edge of the State Streets neighborhood. The park is bounded by a street called Arsenal. So named because it led to the U.S. military’s arsenal of weapons and ammunition used throughout the West. In thinking about the sheer numbers of soldiers and settlers that passed through this site and about the white supremacists who used the Park to stage a campaign of terror later, I began to understand, in this place, that the visual experience of St. Louis would have been one of brute force and violence. I began to think about sound and ephemeral media as a mechanism for finding solidarities outside of the visual that could decenter or offer a different experience. For example, I invited Raven Chacon to work in this space because of the ways his performance and sound installations provide new models for assembling in space.

The city also has a complicated identity and history as the edge of the South, let's call it, because of Missouri’s contentious relationship with slavery. St. Louis was a passageway into places north, like Chicago, where I live, and a space for fugitive people escaping the confines of slavery to move through or relocate to. This history is why St. Louis has such an incredible history of Black contributions to not only national but world culture. Jazz, Josephine Baker, and all the incredible people from St. Louis are entangled in this longer history of the city as the edge of the South. The way that prison abolition is practiced and theorized today since the publication of The New Jim Crow, especially in art exhibitions, is deeply tied to the South and the abolition of slavery in the U.S. But how do we construct an abolition that also includes the West?

St. Louis, as the gateway to the dispossession of the West on the edge of the South, was the perfect ground for thinking about the concurrent histories of slavery and dispossession and to pull together these lingering questions from Monarchs and Walls about how to marry abolitionist and decolonial methods. Working within these historical frameworks and theoretical parameters, the questions that I had for Counterpublic, then, were: How do I make a public art exhibition that does not restage an occupation? What material forms could show what has been erased from the city, reveal how carcerality or coloniality are inscribed into the city itself, or conversely, show us a future beyond that organizing structure? How could those forms also evade surveillance and live outside the possibility of being policed, captured, and contained, even as an image? I landed on sound, but also plants, dirt, clay; all elements that were already a part of the fabric of a place but that are often taken for granted, realizing how ecology and the literal land are entangled in the same systems.

ZD: It's so interesting to think about this kind of project in the context of what is technically a triennial, which brings to mind the tradition of triennials and biennials, connections to spectacle and imbrication with the market, capitalism. The ways you’re describing your intervention, and Counterpublic as a whole, seem to be working against much of this, especially in how visibility and visibility politics are employed. Engaging in visibility politics, but avoiding creating a spectacle, feels like a delicate balance.

RP: The worst experiences that I've had at perennial exhibitions feel akin to art treasure hunts with exhibition guides functioning like a map. Visitors are rewarded with an artistic experience that engages with a city’s history, often creating a spectacle for a city’s most traumatic places. I’ve had experiences of navigating other people’s hometowns through artworks made by outsiders who showed me a very painful history in ways that I thought were unethical or at the very least, callous. And I was also thinking—everybody in Counterpublic was thinking—about how St. Louis’s community was Counterpublic’s primary audience. What is our ethical responsibility to them, their communities, homes, and histories?

ZD: Yes, exactly. Based on that, I'm curious how you came to the projects that you ended up executing and why you felt that those were sort of an answer, or an offering, to the questions that were framing your thinking?

RP: I thought deeply about what it meant to make any sort of gesture in a place that I have no claim to—and that has no claim to me—as a guest in that space. I really wanted to tread lightly and invite artists with a similar ethic. So the first thing that James [McAnnally] and I did was write to the Osage Nation and ask them for formal permission to make Sugarloaf Mound—the last remaining mound in St. Louis, a place once called Mound City—one of the terminal sites of the exhibition and to begin a relationship. Early in the process, I also made a declaration that Sugarloaf Mound, a site of Osage cultural and spiritual significance, should not be considered as a potential site for artistic engagement. I felt any intervention into that space could only function as a trespass. Literally, because to cross the fence that surrounds Sugarloaf is to trespass on Osage Nation, who purchased it as property reclaiming this important ancestral site as an extension of the Nation from their displaced territories in Oklahoma. And conceptually, because to think about the layer of artistic intervention atop this site also seemed to negate the Mound itself and the very long history it has both experienced and witnessed.

Instead, I invited Osage artist Anita Fields and her extended artistic family to work in the field adjacent to Sugarloaf Mound. Anita created an incredible installation called WayBack that speaks to displacement and the homecoming that Sugarloaf Mound represents. Anita’s youngest son Nokosee composed the sound component for the installation and her eldest son Yatika helped organize the closing events: a production of Wahzhazhe Puppet Theatre’s “Sky E.Ko Tells Stories of Way Back,” about Osage history from creation to today, written, directed, and produced by Anita’s daughter, Walena Quenton, in collaboration with Candice Byrd-Boney and Russell Tallchief.

This is another angle to how I came to the idea of making a public art show that did not restage an occupation and could evade surveillance: How do we not replicate the systems that we’re imbricated in?

On one hand, these present but overlooked forms like sound and plants led me to artists Raven Chacon and jackie sumell.

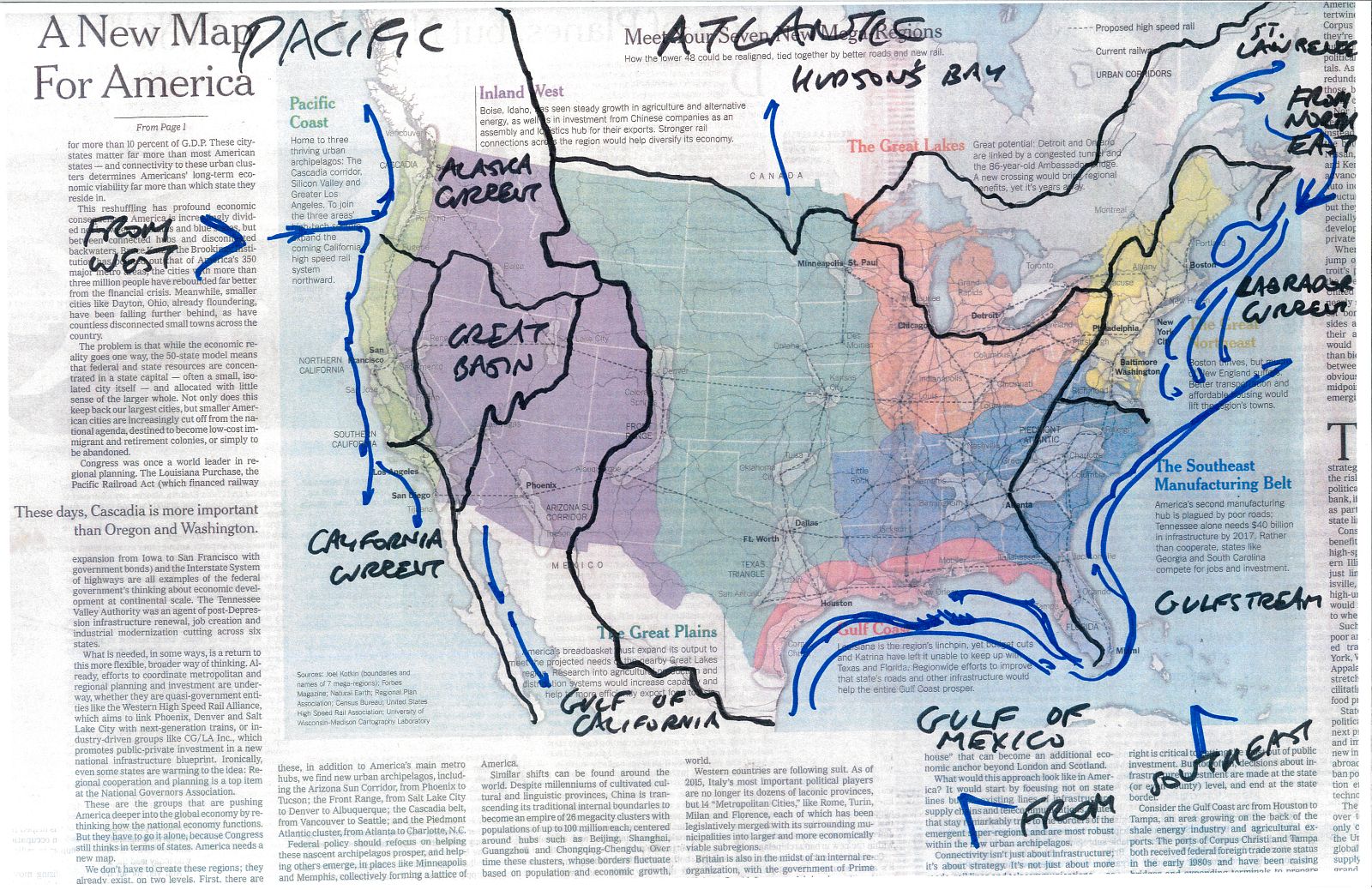

The mound-building culture that produced Cahokia, the largest mound in North America, and other mounds along the Mississippi River Basin, were connected by rivers. So I also began thinking more expansively about artists who had an ancestral relationship to St. Louis through these rivers. Anita and the Fields family are ancestrally from St. Louis and the greater Missouri area. Cannupa Hanska Luger is from North Dakota, which is linked to St. Louis through the Missouri River. I worked with Cannupa in Monarchs and appreciate the expansive position from which his works engage Indigenous futurity through ancestral and contemporary technology. X is Coushatta, a mound-building culture from Louisiana (and Chamorro) and has been making contemporary mounds throughout the Midwest. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith made a new map painting in response to St. Louis. In our conversations, she spoke about how the Missouri River connects St. Louis to Montana, where she is from. And it is by following this river that French settlers made it to Montana, enabling the French fur trade. We installed Jaune’s painting and also a canoe made of the wood of the Osage Orange tree and filled with artist-made replicas of the kind of objects that the French would have traded with Native people at MONACO gallery, which is located in the middle of the State Street neighborhood.

ZD: That brings us to the larger 'State Streets' project as well, which was also deeply inspired by both this specific place in St. Louis and by Jaune’s work.

RP: I have so much gratitude to ICI for supporting the research and production of a project that is very much still in process. And to Jaune, whose paintings have taught me so much and have inspired my thinking, not only for this exhibition but also for how I understand the United States, as a geography and as an entity.

On my first site visit to St. Louis, the State Streets neighborhood reminded me of the map paintings Jaune has been making for the past 50 years because of how the logic of the U.S. map is overlaid onto real space there. In that neighborhood, all the East-West streets are named for Native tribes and all the North-South streets are named for U.S. states. There are a lot of cities that name their streets this way. But in the context of St. Louis’s instrumental role in dispossession, the intersection of Osage St. and Missouri Ave. in the State Streets neighborhood indexes the history by which Osage Nation was forcibly removed from its ancestral homelands in the process of establishing Missouri’s statehood on the very ground where that removal happened.

There are a dozen or so intersections in this neighborhood with similar references: Wisconsin and Chippewa, Ohio and Miami, Minnesota and Dakota, Tennessee and Cherokee… In talking to St. Louisans and the neighborhood's residents, I learned that history is now abstract and removed from the community consciousness. Where residents saw the intersection of Tennessee St. and Cherokee Ave., I saw a reference to the Trail of Tears. The route through Missouri is just over 100 miles south of St. Louis. I responded to this space in two ways: First, I invited Jaune to the exhibition and was heartened to hear that St. Louis was a place she thought about often as it was the departure point for the French traders who made their way to her part of the world in the 18th century. Next, thinking about how public space was Counterpublic’s exhibition space, I also proposed to ICI that I “relabel” the State Streets neighborhood with information that could draw out the histories embedded in a street naming device.

What I learned from Jaune’s work in this context is how rivers are another form of placemaking and wayfinding, a means of inhabiting space and a method for navigating it that is an alternative to the imposition of colonial borders that the map of the US depends on. To further support Jaune’s work in this place, Counterpublic’s Director of Exhibitions, Jessi Mueller, and I decided to echo some existing signage in the city: In this neighborhood, you’ll see these bright yellow signs to make public service announcements, encouraging residents to buy local or not smoke weed near a school, for example. We adopted that style of sign, calling them “Erased History Markers.” So, for example, at the intersection of Missouri Ave. and Osage St., we created a sign that presented information about the series of 40-plus treaties in the 19th century that over time moved the Osage from Missouri to Kansas, and then to Oklahoma, where the Nation is now based.

Tracing a history of displacement on the static marker of the sign in the place from where people were originally displaced is an important aspect of the project, but so is etymology. Jaune’s paintings are also about naming systems and the language of place. So many states are named for Native people or appropriate Native place names. The signs were also opportunities to present alternative systems for naming and navigating space, extending Jaune’s painting into the neighborhood. And it's wonderful that the St. Louis Art Museum purchased Jaune’s painting and canoe for their collection so that they can continue to be in dialogue with the city.

ZD: That leads me to ask about some of the bureaucratic challenges that the project faced or the bureaucratic processes that it instigated, the conversations it prompted among you, the city, Native groups, and the artists. What is the status now?

RP: Some temporary signs were floated up for the opening, but we are still on hold with the City of St. Louis, which is undergoing a process of vetting the signs through their systems. This vetting includes reaching out to the 11 Nations referenced in the signs—meaning that there are 11 moments in the State Street neighborhood where a street named for a group of Native people intersects with a street named for the U.S. state that was created in the wake of the removal of those Native people from their ancestral homelands. (We consulted with Osage Nation before submitting the signs to the City of St. Louis). The city is not trying to censor the information; they want to make sure that the history written is reflective of the individual Nations’ version of that history.

At some point in what has become a very long process, I began to think that it's good that they've been hung up at the bureaucratic level of the city for so long. In proposing these signs to the city, we began a conversation about how streets are named in this neighborhood, which then unfolds a longer history of St. Louis’s role in dispossession. I think that having the opportunity to present a set of information to the city then became as interesting as putting them in the streets.

ZD: That’s an intervention in itself, absolutely.

RP: One thing that makes Counterpublic different from other perennial exhibitions is that it doesn’t get mired in the metaphor that “art creates change” through a passive viewing experience. Instead, the showmakers emphasize how the conditions by which art is incorporated into a place open the possibility of leveraging opportunities to create change. There are multiple moments in the show where each curator engages in a process to make a concrete change in the city. New Red Order has been working with property owners to repatriate the remaining portions of Sugarloaf Mound to Osage Nation. Curator Diya Vij worked with artist Jordan Weber to create a rainwater garden and park in a neighborhood that had no designated outdoor gathering space. We all saw the exhibition as an opportunity to have a conversation with the public.

Getting back to the decision to work with material and immaterial forms that evade capture, I think the process the signs initiated is a request for an ideological shift. These street signs function similarly to how monuments function, to inscribe an ideology literally in the streets themselves. Through this vetting process, we are indirectly asking the leaders of the city to grapple with the city’s history. When the signs make it to the streets—and Counterpublic is lobbying that they become permanent inclusions in the neighborhood—the public and the neighborhood’s residents get to be a part of this conversation. What is their response? In the process of interacting with the history of why their streets are named, maybe the neighborhood will choose something different.

ZD: Absolutely. And it’s striking the way that this displacement is also sort of doubly indexed in all of these individual slices of property that now exist there with these names as their addresses—the contrast of understanding the displacement and then going in and using your key to unlock your home that you get to own. It’s pretty remarkable.

And I'm curious: Did the city have these relationships with the Native communities beforehand? How robust was their communication with these groups in advance of your intervention?

RP: While I can’t speak for the city of St. Louis or the State of Missouri today, I do know that in fashioning its identity as the gateway to the dispossession of the West at the edge of the South, the state of Missouri made it illegal for Native people to be in the state until the 1920s.

I also know that at the same time that Counterpublic was being organized for its April 2023 opening, a group of people from St. Louis’s creative and academic institutions, working under the name Indigenous St. Louis Working Group (formerly The STLr City Working Group), have begun an incredible process of reconnecting with all the displaced tribes of Missouri that were relocated to Oklahoma. The group formed in response to a call from St. Louis University to think about the city and state’s history of segregation. In The Broken Heart of America, Walter Johnson argues that the eviction of Black communities from St. Louis City to the outlying St. Louis County, where Ferguson lies, operates by the same mechanism that dispossessed Osage, Fox, Sauk, and other Native peoples ancestrally belonging to Missouri and beyond, to reservations in Oklahoma. That Native removal is a template for segregation, and in this case, Native people have been segregated to another state. Missouri has no reservations, while Oklahoma, which shares a border with Missouri, is home to 39 tribes, the majority of whom were removed from the Eastern half of the United States after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and from Missouri itself. The Indigenous St. Louis Working Group is doing very important work to begin to build relationships.

ZD: I remember in a previous conversation we had, you were talking about the different theories of cultural change—the radical, pull-the-rug-out-from-under-everyone model versus the slow burn. And that there’s a time and a place for one or both of those to come into play. Obviously, we often wish change would come in the form of pulling the rug out, but I think in some cases the slowness is necessary, the building of trust, of communication. And I think it's so rare that an art intervention can actually state that intent, and then do it.

RP: I appreciate your memory! The idea that art creates change through a viewing experience is rooted in an avant-gardist idea of acculturation: that a viewing experience causes an internal shift in an individual and over time a cultural shift in society; artists lead the way. This kind of change is very much a slow burn, especially in contrast with the popular imagination around a Marxist revolution. Then there is something in between revolutionary overhaul and small internal shifts: Direct action like the strikes of worker’s movements, sit-ins of Civil Rights campaigns, ACT UP’s spectacular civil disobedience campaigns, rely on a critical mass of people focusing their collective power towards a specific goal. I’m particularly indebted to the last two examples which guide my methods of withdrawal, negativity, and refusal throughout my work.

But, the model of change that I and others employed at Counterpublic is something different than all of the above. Lauri Jo Reynold’s definition of legislative art, which intervenes in larger government systems through processes of lobbying stakeholders and campaigning to decision-makers. The triennial format, but also the class structure of the art world in general, gave us an opportunity to be proximate to those groups as culture brokers. I’m also thinking of the phrase “a wrench in the system” which describes interference in working order. But a wrench is also a tool that can be used to tweak a system as well as to disrupt it. It’s the intention that one brings and the force that one applies that makes the difference between tweaking and disrupting, which itself is the difference between reform and abolition. I’m not a reformist, but I like the idea of working both angles at once, small actions, reforms, that accumulate into a systemic shift resulting in the abolition of the original system. Building as we dismantle.

It’s interesting to think about the time of change as it intersects with the time of an exhibition. I think of the exhibition itself as a window into a process; it is the time that the public gets to see the result of the artistic, curatorial, and administrative labor that has taken place up until that point of the opening. The exhibition morphs throughout its run as artists, agents, and viewers intersect and interact. But, the work begins before the exhibition opens and continues after it closes.

This Curatorial Research Fellowship is made possible by the Marian Goodman Gallery Initiative in honor of the late Okwui Enwezor, and the Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation. Additional support is provided by ICI's Board of Trustees and Leadership Council.

Risa Puleo is an independent curator and one of a team of curators organizing the 2023 Counterpublics Triennial in St. Louis.