Marina Reyes Franco, recipient of the 2017 CPPC Travel Award, reflects on her research trip to The Bahamas, its colonial history, the hotel industrial complex, and the impact of tourism on cultural production.

In An Eye for the Tropics, art historian Krista A. Thompson explains that the images of Jamaica and The Bahamas as tropical paradises full of palm trees, white sandy beaches, and inviting warm water seem timeless and natural but their origins can be traced back to the roots of the islands’ tourism industry in the 1880s. During that period, tourism promoters backed by British colonial administrators and American business interests began to market Jamaica and the Bahamas as the origin of their desirable fruit products and picturesque destinations. They hired photographers and artists to create carefully crafted representations, which then circulated internationally via postcards, illustrated guides and even “magic lantern” lectures given by photographers who created the images and narratives to suit specific business interests. Corporations like United Fruit Company used their “Great White Fleet” boats to transport bananas from Jamaica —the original “banana boat”— but they also transported tourists. Iconic hotels such as the Myrtle Bank Hotel in Kingston and the Colonial Hotel in Nassau served as racialized spaces of power.

Throughout my trips around the region, Thompson’s book has been a point of reference and blue print for my approach, but in The Bahamas and Jamaica I was actually able to revisit the sites she was referring to. The visions of each country are framed through tourism campaigns, developer’s plans, brochures, travel guides, Airbnb, as much as they are by historical constructions and preconceived notions. I traveled to The Bahamas in October 2017, eager to connect with contemporary artists, institutions and independent spaces to learn about the impact of tourism in cultural production, but also about the service industry in general, the creation of resorts, cruise ship ports, and the privatization of beaches. The hotel or resort is an interesting subject that would come up again and again during these trips. I went to many hotels during my visit to The Bahamas and some, I was surprised to find out, also aim to be public cultural spaces.

Image: Cruise ships overpower the view of Downtown Nassau.

The Bahamas are limestone islands, not volcanic like the vast majority of the Caribbean islands. This shaped its original flora, but its landscape was subsequently altered to better fit tropical narratives and the expectations of tourists from the early 20th century, and more intensely after World War II. The postcards, lectures and advertisements served the purpose of turning what used to be seen as an unsanitary, disease-ridden region, into a paradisiacal place that was also good for your health. This sanitization of the Caribbean for tourist consumption encompasses architectural, health and urban planning aspects as well as public relations and media strategies. Eventually, the beaches were privatized to keep the “natives” out, pools were installed and the all-inclusive resort came into being.

There is a direct link between the plantation model of foreign investors and rich enough to be absentee owners, and the economies of industrialization by invitation that was prevalent in Puerto Rico and other Caribbean countries in the 1950s. The plantation of the past is, sometimes quite literally, the resort hotel of today. Former plantation lands in Montego Bay or Negril serve as hotel sites and tour destinations where most Jamaicans don’t go unless they work there. Although the situation in The Bahamas regarding private beaches, islands and cays is similar, the plantation to resort pipeline is not as straightforward as in Jamaica.

Image: Installation view of the Revisiting An Eye For The Tropics at the NAGB.

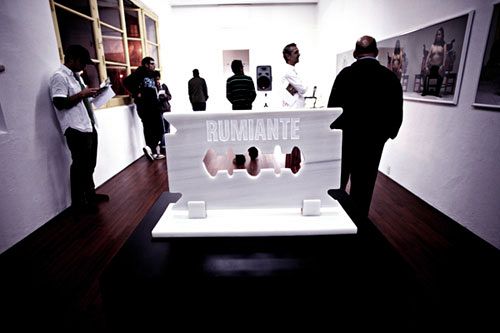

One of the main reasons for wanting to go to The Bahamas was to have a first hand account of Revisiting An Eye For The Tropics, an exhibition curated by Natalie Willis and Richardo Barrett, at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. The show, which presents pieces from the NAGB’s collection as well as other private collections, examines the work of over 20 artists and presents “a look into how our visual representation as a nation throughout history has been shaped as a result of the desires of colonial era tourism.” From colonial postcards and works by traveling painters, to art produced by pro independence Bahamians, and contemporary installation, the exhibition offers a rich look into art produced about The Bahamas and by Bahamians who want to rid themselves of those representations. As Natalie Willis, co-curator of the exhibition, wrote in an article for The Nassau Guardian, there are questions of provenance and national identity that are linked to the collection of the NAGB: “What constitutes Bahamian art?” she asks. What role do American and British travelers, who generally produced “quaint ‘old world’ charm watercolors in the late 1800s to early 1900s” play in the art history of The Bahamas?

Colonial era expatriates, many of them American, painted the perceived quaintness of Bahamian life and landscape, which played into the idea of The Bahamas as picturesque, and the “native” black population as docile and respectable. One such portrayal of the Caribbean picturesque in Revisiting An Eye for the Tropics is American watercolor painter, Hartwell Leon Woodcock’s “Native Hut” (1915) —which depicts a hazy outdoor scene of a house framed by poinciana and palm trees— and William Sweeting’s ‘Two Natives at the Gate’ (1971) —a realist oil painting depicting a lone Black man in a donkey-pulled carriage, passing a fancy garden gate. The selection of works like these for the exhibition is not necessarily for their outward beauty, but for the questions that arise from their titles, the national origin of one of the artists, the fact that they’re in a national collection and how that came to be. Indeed, some of the works in the NAGB collection where donated by financial institutions whose interests were served by perpetuating certain representations of Bahamian life as depicted in such paintings. The exhibition is not only about the colonizer’s gaze, but also delves into the impact its had in contemporary artists. What does art say about a place, about the people making it, collecting it and choosing to associate national identity to it? Among the artists included, are Brent Malone, Kendall Hanna, Antonius Roberts, Blue Curry, Max Taylor and the fantastic intuitive artist Amos Ferguson. Other standouts are Sanford Sawyer’s 1970s studio photography depicting “Over the Hill” Black Bahamians and Dionne Benjamin-Smith’s digital prints of recognizable Bahamian scenes: seascapes and quaint houses with trees and flowers pouring out of the yards into the empty street, which were then intervened with texts such as “this is real Bahamian art,” “requires no explanation,” or “no abstract art here.” Her work is a tongue in cheek critique on the accepted modes of representation in Bahamian Art. While I was visiting the show, I had a random thought about the influence Hanna, an abstract expressionist painter, might have had on contemporary artists who felt the need to break from landscape and figurative painting.

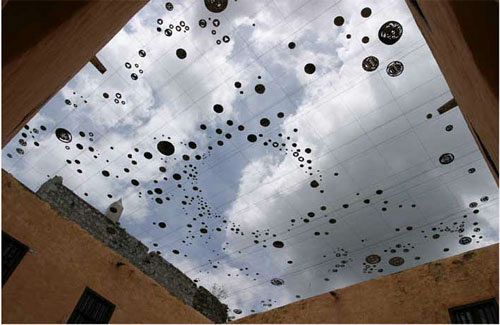

Even before my visit, I was happy to find out about the great online presence the NAGB has. Whether it is by documenting their collection, building an artist directory, showcasing exhibitions, running a blog with frequent posts by curators and cultural studies scholar Ian “Tony” Bethell Bennett, or posting videos of artist talks, the NAGB is on it. Under the leadership of director Amanda Coulson and chief curator Holly Bynoe the exhibition program has introduced a series of artists from the rest of the Caribbean and the diaspora to Nassau audiences. During my visit, I also saw Re: Encounter, which featured Tesselation, an installation by Bahamian Dede Brown and works by Joiri Minaya, a Dominican artist living in New York. I was particularly struck by Minaya’s work: a penetrable wall constructed out of flowery stretch fabric, postcards with a proposed intervention on a prominent Columbus monument down the street, and the poignant video Labadee, about her own experience taking a cruise ship to Royal Caribbean Cruise Line’s tourists-only enclave in Haiti.

Tasked with promoting and preserving Bahamian art, the NAGB also curates a series of traveling exhibitions in various cultural centers in the Family Islands. The National Gallery has benefitted from a close working relationship with The Nassau Guardian newspaper, which runs regular articles about the exhibitions and serves as a platform to distribute the curators’ research into particular pieces from the collection. Coulson also has a radio program titled Blank Canvas on Guardian talk radio 96.9 FM featuring local and international guests to discuss their work, and for which I was a guest too. This is all part of the efforts to make the NAGB a more open space and be less viewed as the aloof, elitist space that its urban placing and colonial architecture might communicate to Bahamians. The problem is, of course, that being such a vocal institution also has its draw backs: it’s lonely out there and there’s seldom other critical voices. This thinking is as much about cultural development as it is about a smart, long-term marketing for the country as a whole. In an interview with The Nassau Guardian in 2011, Coulson pointed out how The Bahamas needed to figure out the importance of the cultural tourism sector: “People go on vacation and they don’t want to lie on the beach; they want to go see art. Those people are in a much higher income bracket than the tourists we generally are advertising to,” she pointed out. “Cultural produce is something we can trade on and we are not attracting cultural tourists right now because they do not realize there is a valid system of museums and galleries and practicing artists down here they can discover.”

The Bahamas is perceived through its role in the world tourist economy and imaginary of the island paradise and hotel complexes that seek to capture people’s fantasies. Atlantis is the paradigm of the immersive hotel experience of being and not being there. Located in Paradise Island, a private island formerly known as Hog Island, the resort controls around 75% of the land. Atlantis was established in the mid 1990s, with the fantastic tale of the rediscovery of the lost civilization in The Bahamas conveyed through the resort’s architecture and attractions in a way that is more Las Vegas than Caribbean. The main draw for the non-paying public is the aquarium, a tunnel that allows you to walk amongst the sea creatures and fantastic suits and decoration of the “real” Atlantis. This attraction seems to complete the fantasy explored in the early days of tourism with the glass bottom boats or underwater capsules.

Image: View of the Atlantis aquarium in Paradise Island

Meanwhile, in New Providence, the main island in The Bahamas, there’s Baha Mar, a resort complex comprised of 3 separate hotels in the same “campus”, a convention center and a golf course. It is the largest and, at $3.5 billion, priciest resort in the Caribbean. The story of Baha Mar is long and very interesting —it started in 2005 with local investor Sarkis Izmirian striking a deal with the government to revitalize Cable Beach, the most popular beachfront destination in New Providence. The financial crisis made other investors leave, but the Chinese stepped in and provided construction work and money to finance the project. After a bankruptcy left the project in the air, the resort finally opened last year and the original plan of having Bahamian art take a center stage in the project continued. The Current is located within the Baha Mar campus and describes itself as “a hub for compelling Bahamian artistic experiences. A center for recognizing and supporting a strong creative community through captivating exhibitions, workshops and lectures, artist residencies and partnerships with local collectors.” The Current is technically under the marketing department of the resort and has been tasked with commissioning new Bahamian art for the hotel rooms and common spaces. The collection is the largest in the country: over 2,500 pieces in the rooms, restaurants and common spaces around the resort. Baha Mar Creative Director John Cox, an artist and former chief curator of the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, leads the endeavor. The Current has multiple goals from commercial to educational. It will hold exhibitions that explore the depth of Bahamian visual creativity and history through their partnerships with the Dawn Davies and D’Aguilar Art Foundation collections. They also want to establish collaborations with the NAGB, as well as continue with the artist residency program, drawing sessions, and regular portfolio critiques.

Image: “Shake, Swing & Goombay" by Max Taylor on view at the Blue Note Piano Lounge in Baha Mar.

This is all meant to boost the profile of the country as much as the hotel’s but at the same time I worry that the mammoth endeavor has, for years now, conditioned the production of art in such a small country. Some of the pieces highlighted on their website tell a familiar story, but also say a lot about the current Asian economic presence in The Bahamas: Dominic Cant’s installation From the Sea uses photography and sculpture to create an immersive environment that gives the sensation of being underwater. Jordana Kelly’s The Jewels of Baha Mar consists of a wall installation of several Asian-inspired parasols (reminiscent of the ones also found in “tropical” drinks) that are infused with the “bright vibrant colors of Junkanoo.” What I do like is Baha Mar actually having paid the artists for their work instead of —like I’ve seen happen in Puerto Rico and was told about in Jamaica as well— have artwork lent to hotels in the hope of selling some pieces there. Beyond this, what is more interesting to me is how the public programming includes workshops, tours of on site and off site exhibitions and collections, critiques and artist talks, making The Current a space that also serves locals and art students. One could even argue this demographic is the main beneficiary until The Bahamas builds a brand around cultural tourism. The future exhibition ambitions of Cox and The Current staff will not only be part of the attractions in the hotel complex, but have the potential of being a welcome (and funded) addition to the cultural scene in Nassau.

Another hotel that is part of the Bahamian art scene is The Island House, a boutique hotel just outside the gates of the exclusive Lyford Cay community in western New Providence. Since opening in 2015, director Lauren Holowesko has developed a program of art exhibitions, music, film and a burgeoning residency program. TIH also has a cinema open to the general public and recently inaugurated an intimate one-screen film festival managed by artistic director Kareem Mortimer, who is an award-winning Bahamian filmmaker. My visit coincided with the exhibition My dreams aren’t your dreams, curated by Tessa Whitehead, an artist and curator of the local The D’Aguilar Art Foundation. I saw several of David Gumbs’ interactive video installations at TIH, along with some work by Bahamians Heino Schmid, Spurgeonique Morley, Averia Wright, Whitehead herself and Jamaican Deborah Anzinger, to name a few.

Image: Conch shells sell for $5 USD in the Nassau port. Overfishing to supply both local and tourist tastes is a big problem in the islands.

The Bahamas is, simultaneously, the site of crystal clear waters and obscure financial schemes, where monster hotel projects and high-end real estate coexist with a majority of people who haven’t benefitted quite as much from the country’s fiscal plans since independence. I’m not sure using financial terminology to talk about an art scene is ever correct, but maybe The Bahamas is the place more apt to do this. Diversification is necessary, be it economic —by not over-depending on cruise ship traffic to Nassau— and artistically —by not only relying on hotels to foot the bills of the artistic production of the future. I was glad to find in the NAGB a self-reflecting institution that understands its role as caretaker of collections but also connectors to a wider Caribbean reality and network of creators and thinkers. Throughout my time in The Bahamas, I found people with the intelligence and business savvy, who see the possibilities of bridging the gaps between what the country needs to move forward economically and what it takes to have a healthy artistic scene. To paraphrase Natalie Willis, the aim now is to dismantle inherited hierarchies and histories crafted by people who looked at Bahamians through their own, racist, colonial, patriarchal, lens and “make ourselves present in three-dimensional vibrancy too.”