In this 2022 essay, editor, writer, and curator Dessane Lopez Cassell responds to the work of Interrupting Criminalization on view in Notes for Tomorrow. The collectively-curated exhibition, conceived by ICI, takes the events of 2020 as a jumping-off point for a radical reassessment of our present. The work of Interrupting Criminalization was selected by Chicago-based curator Ross Jordan (Curatorial Intensive alum, New Orleans 2016) as part of a larger work called "A Liberated Library for Education, Inspiration, and Action." Jordan selected two resources published by Interrupting Criminalization as part of the library of "zines, booklets, and guides created by artists and community organizations based in Chicago [that] provides tools, vision, and inspiration for community transformation." Here, Cassell extends the reach of A Liberated Library to a 2022 publication by Interrupting Criminalization, assessing how our ongoing moment of cultural transformation continues to reverberate.

August.

A dead rat has been decomposing on my street for weeks now. Laying in morbid repose in the middle of the sidewalk, just far enough from the McDonald’s parking lot and the maintenance perimeters of the nearby buildings. A tiny strip of urban no man’s land as far as the street sweepers are concerned. By virtue of its final resting place, the rat has become no one’s responsibility, and perhaps also everyone’s.

September.

It’s been six weeks and still no takers. Oddly, no disturbance or desecration, either. What’s left of the rat is now glued to the concrete in the late summer heat, wisps of fur blowing in the occasional breeze.

One night, after a couple drinks, I become convinced that someone is making art about it: guarding it stealthily from a hidden perch, ensuring no dogs, cats, or mischievous teens interfere with it. This is New York, after all, and space is perpetually overpriced and in short supply.

Or maybe I’m that someone.

October.

From what I can tell in observing my neighbors, no one—except me, I guess—seems concerned about the rat. Since 2020, pandemic-induced budget cuts have slashed $2.2 million from New York City's sanitation department. The backlog of garbage has yielded a resurgence of critters of all kinds, keeping residents (and the internet) plenty busy with jump scares and absurd TikToks.

And while this particular rodent may have met its end, what’s left of its corpse feels like a metaphor for the way the U.S. handles most problems. Ignore it long enough and it might just go away. It’s a strategy that relies on collective apathy—itself a side effect of this nation’s founding myths of self-sufficiency and thus, the blame of individuals for their own adversity and trauma.

In some ways, living in New York requires constant confrontations with death, and I’m not talking about the hysteria around “rising crime” into which many have been fearmongered. It’s the quiet, slow death that exists at every turn in one of the most expensive cities in the world. The death and depletion of those who have less at the hands of (or to benefit) those who have more through neglect, bureaucratic indifference, and the constant denial of resources that could meaningfully alter the scales.

This attention to the ways in which resource distribution and mortality intersect underpins the work of Interrupting Criminalization (IC). Founded in the fall of 2018 by activists Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie, the research initiative aims to “interrupt and end” the ever-increasing criminalization and incarceration of women, LGBTQ+ people, and gender-nonconforming people of color. More specifically, their work focuses on the ways in which concerns around public order, poverty, child welfare, and drug use have enabled the criminalization of survivors of violence.

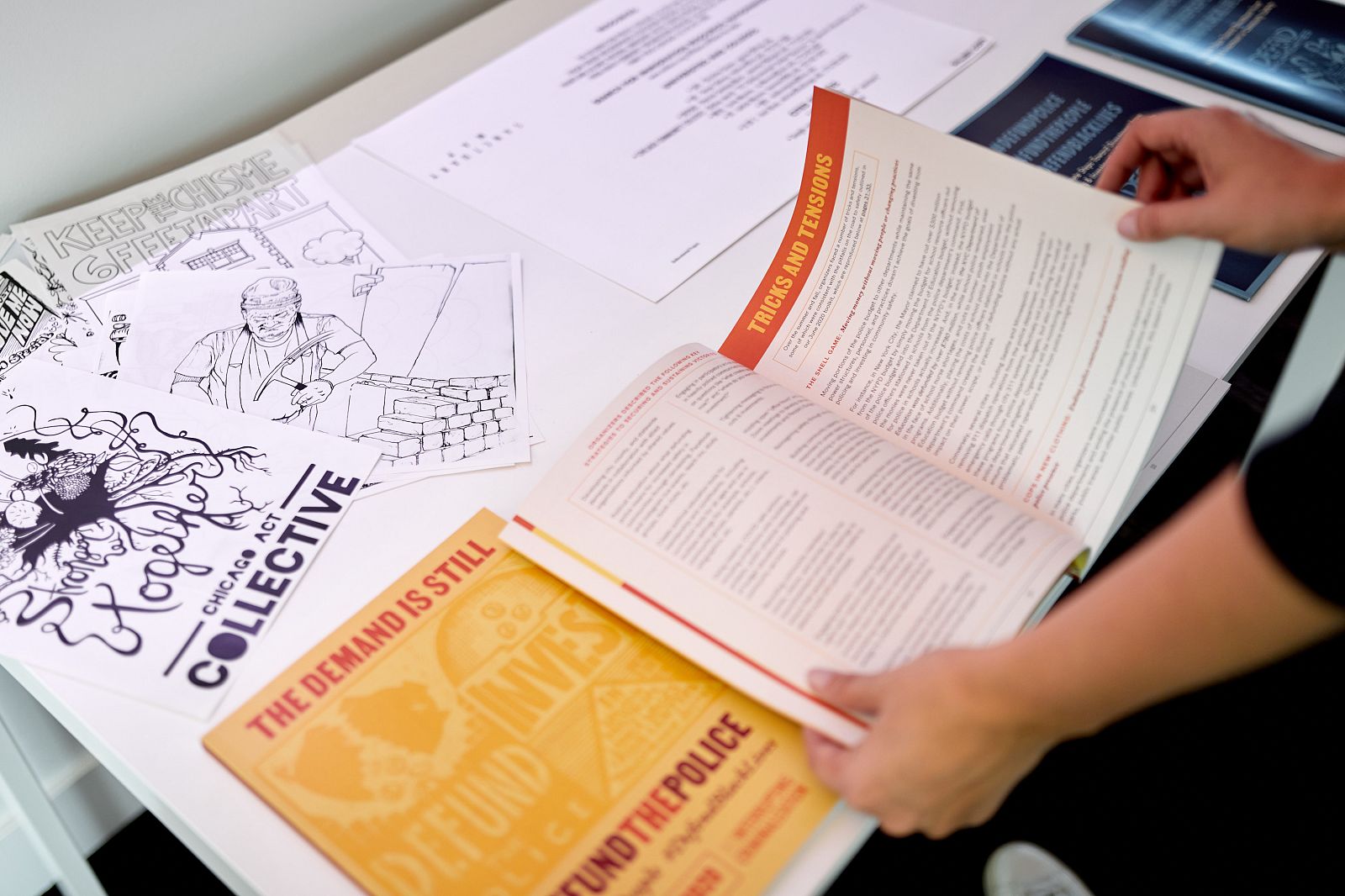

Through their zines, fact sheets, and resource guides, as well as scores of abolitionist writings, Interrupting Criminalization presents alternative mechanisms for working toward a safer society, ones that prioritize agency and self-determination over police reliance and the existence of perfect victims. In both content and form, their work stresses the importance of community involvement, reminding us that it is impossible to work towards an equitable notion of safety if the individuals most impacted aren’t permitted a real say in defining how that safety should look and feel.

The work of Interrupting Criminalization isn’t what one might normally expect to find included in an art exhibition. And yet, amid the uncertainty and necessary recalibrations that characterized some of the darkest days of the early pandemic, the Chicago-based curator Ross Jordan selected some of their writings for inclusion in ICI’s Notes for Tomorrow.

The traveling exhibition takes the COVID-19 pandemic “as a jumping-off point for a radical reassessment of our present,” with thirty curators from around the world—all alumni of ICI's Curatorial Intensive—invited to select artworks that engage with decolonization, notions of social transition, and the tasks of creating and sustaining cultural memory. The works are largely photographic, moving image- or text-based, and have traveled digitally from Nevada to New Zealand, and the exhibition will make its final debuts in June at the Parallax Art Center and SUNY’s Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, in Portland, OR and New Paltz, NY, respectively.

Like many projects born of the early pandemic, it reflects an emphasis on collectivity as strength, a rejection of the individualistic modes and policies that have long pushed communities towards precarity. As the pre-2020 dates of many of these artworks reveal, such precarity is, itself, nothing new; what’s novel are the floodlights that this pandemic has cast upon it.

As Ross Jordan has himself reflected in the curatorial notes for “A Liberated Library for Education, Inspiration, and Action” (the broader installation in which Interrupting Criminalization’s publications have been included), “In 2020, many people across the United States, in the middle of a public health crisis and racial reckoning, are re-thinking what is needed to make communities truly healthy and safe.…Community organizers and artists, in their resistance to neglect and state- sanctioned violence, present these zines and share knowledge gained from local action, so that we all can imagine the communities of the future and the steps we need to take to get there.” As we wade through a bleak present, it’s that last part—about imagining next steps—that feels most key.

Installation view, Notes for Tomorrow, Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2022. (Photo: Miranda Alum/UNLV Creative Services)

A Liberated Library for Education, Inspiration, and Action, installation view, Notes for Tomorrow, Pera Museum, Istanbul, Turkey, 2021.

A Liberated Library for Education, Inspiration and Action, Notes for Tomorrow, installation view, Notes for Tomorrow, Contemporary Calgary, Calgary, 2021. (Photo: Jesse Tamayo)

A Liberated Library for Education, Inspiration, and Action, installation view, Notes for Tomorrow, Blue Galleries at Boise State University, Idaho, 2022. (Photo: Wytske Van Keulen)

Lately, I’ve found myself mulling over a featured set of principles released by IC in early November 2022, called “Beyond Do No Harm.” Developed by a group of community organizers and public health care workers and providers whose work together began in 2019, the principles offer a framework for what it might look like if health care providers and workers could, well, actually care for the people they serve, instead of being forced to follow the inane defensive procedures of a profit-driven insurance system.

At its core, “Beyond Do No Harm” is a call to action. Each principle urges a shift away from diagnostic and reporting systems rooted in surveillance and medical racism, and toward systems that can support actual well-being and autonomy. Specifically, they call for the following:

Interrupting Criminalization, "Beyond Do No Harm"

1. End police and ICE presence in hospitals, in or near health care facilities, and in places where people are accessing care.

2. End medically unnecessary information gathering, documentation, and surveillance.

3. End medically unnecessary screening and testing without consent.

4. End the practice of calling police on suspicion of fraudulent identification documents.

5. Stop calling police on people with unmet mental health needs.

6. Stop calling police on people in possession of, distributing, or using drugs and controlled substances.

7. End mandated reporting.

8. Stop supporting prosecution in cases against people who manage their own care or offer community-based care, fail to seek care, or fail to disclose their private medical information.

9. Stop participating in or supporting prosecution in cases of transmission of infectious diseases.

10. Stop participating or supporting prosecution in cases related to drug use or overdose.

11. Stop providing and/or sanctioning substandard/violative care for people who are in custody or incarcerated in jails, prisons, detention centers, residential centers, group homes, and state facilities.

12. Stop collaborating with the criminal punishment system to violate people in custody, including through performing cavity searches at the request of police or prison officials; evaluating competency to stand trial; experimenting on and sterilizing people who are incarcerated; facilitating torture; or administering the death penalty.

13. Stop punishing other health care providers and staff, public health workers, and researchers by calling police on them, reporting them for disciplinary action, or terminating their employment for their refusal to participate in systems of harm.

It’s an ethos that prioritizes mutual respect and careful consideration of the myriad contexts we exist in as members of deeply raced, gendered, and classed societies—things that should be, but unfortunately aren’t, basic cornerstones of work that involves fellow human beings.

As the artist Carolyn Lazard has written, “The past and present collapse in the experience of trauma. Things stick to us.” We are more than just the sum of our medical, immigration, and criminalization records. Further, if the pandemic has taught us anything so far, it is that we should listen to those closest to a given issue, whether in making decisions about health care or about how we ensure more equitable access to resources and culture. Knee-jerk proclamations, made in a vacuum or to provide temporary solutions, only aggravate things.

In the U.S. alone, upwards of one million deaths have occurred due to COVID-19. One million deaths and counting. It’s a figure so large that it’s become abstract for many of those lucky enough to have avoided the long-term terror of this particular virus, the grief of losing loved ones, the unquantifiable other health, family, and personal concerns still shouldered by survivors.

Chicago ACT Collective, "Somos lo que necesitamos (We Are What We Need)." Resource available at chicagoactcollective.com

Looking back on the urgent optimism of the early pandemic, I often find myself squirming in embarrassment. Not only have our governments failed to enact many of the critical changes that so necessarily demanded, but many of us have also failed to truly internalize the lessons we purported to have learned amid such a destabilizing and formative period. As Colby Chamberlain has written, while reflecting on the work of the artist Park MacArthur, “Whether it be COVID-19, environmental crises, Black Lives Matter, or the recent protests against the Whitney [Museum]’s ties to tear-gas manufacturers, the political cause of our time is the capacity to breathe.” And yet, amid the scramble to return to a capitalist sense of normalcy, what’s dissipated quickest is the affordance of that very breathing room. In the cultural realm, I’ve found myself sitting in quiet disbelief as I witness the rolling back of remote access for live events, the shaving down of rates for freelancers and the other precarious arts workers upon which our ecosystem relies, and even the growing acceptance of once again socializing while knowingly ill and contagious, for fear of missing out. In so many ways, the masks have come off.

Installation view, Notes for Tomorrow, Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz, New York, 2023.

To draw on Chamberlain, what good is a vaccine if it means buying into the norm that all we can do is return to the systems that only ever benefitted those who have the most? I’m not yet sure what a future without those systems could look like, but I do know how terribly one with them would. We’re already living (and dying) in it. Yet, as Mariame Kaba has urged us to consider:

"When something can't be fixed, the question should focus on, what can we build instead?"

A potent note for tomorrow, if I've ever seen one.