José López Serra is a Puerto Rican artist and curator, based in San Juan. He is a co-founder and director of Hidrante, a project space in San Juan, PR. López Serra is also an alumnus of the 2017 Curatorial Intensive in New Orleans.

In the weeks following Hurricane María, he was documenting the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, so ICI commissioned him to produce this visual essay.

Fallen trees and debris in the afternoon of the day Hurricane María crossed the island.

It has been intense, to say the least, after María. I was selected to be a part of this year’s Curatorial Intensive in New Orleans, thanks to a scholarship from ICI and Beta-Local. The Intensive highlighted for me the connection between New Orleans and the Caribbean, and now more so between two disastrous hurricanes. The aftermath of Katrina is still very palpable in New Orleans, with empty lots reflecting the people who have left and the areas that never went back to “how it was.” It’s still too early to say how Maria has changed Puerto Rico; the experience of the Intensive showed me that the process to recovery is very long, and that normality, thought of as a going back to how things were, is not possible. The Huracanes mark a before and after, and they make evident processes and contradictions that otherwise wouldn’t have been brought up.

A US flag was found underneath a fallen tree in Santurce, San Juan.

What the Hurricane [the subsequent process of emergency and stabilizing after it] has evidenced is the multilayered structure of domination that the PR/US relationship entails. Foreign aid couldn’t enter the island directly, as the Jones Law restricts interstate maritime shipping to US flagged, manned, and owned ships. The Law was suspended for 10 days after the Hurricane hit, which meant little, as shipping logistics were all but impossible without consistent telecommunications and shipping lines need more than a week to re-plan their schedules and routes. Foreign aid also had to be cleared by the Federal State Department, which turned down electrical workers from Venezuela and Cuba. A massive $300 million contract was hammered behind closed doors to bring a power company with only 2 full-time employees to restore electrical lines, ultimately being canceled and no progress being made.

“Cuba is an independent country that exercises its own sovereignty and whose priority is to take care of its population’s basic needs in the present while planning for the future. They are about as well prepared as a country reasonably can be for natural disasters. They are also always the first country to offer disaster aid in the Caribbean region. Puerto Rico is Cuba’s opposite: as a colony of the U.S., it exercises no sovereignty, and its government is run by lackeys whose priority is to enrich the local oligarchy while pleasing the colonial masters in Washington and Wall Street. While there has been a genuine outpouring of support from individuals, organizations, and some city or state governments in the U.S. — and especially the large Puerto Rican diaspora — recovery efforts are dominated by the same interests that have been pillaging the island’s natural and human resources since the U.S. invaded Puerto Rico in 1898.”

- Professor Déborah Berman-Santana (“Puerto Rico’s Recovery Efforts Stymied by Colonial Status”, M. Nevradakis, Nov. 11, 2017)

Blood red sap from a fallen tree, recently cut in order to make a road accesible. Clean up of trees and debris was the most important task after the Hurricane, as the storm had made most of the island impossible to reach via car or truck. There are still communities in the interior of the island which are hard to reach, as the rain brought flooding, which knocked out old bridges.

In the immediate aftermath of Maria, only 10% of the island had running water, telecommunications were all but halted, and all electricity had to be generated privately. Pictured here is a mess of cables attached to the end of an extension cord at Hotel La Terraza de San Juan, as guests, neighbors, and random people waited for a chance to charge their electronics.

In Aguadilla, on the west side of Puerto Rico, Crash Boat Beach’s pier was demolished by the storm surge. The structure, originally built by the US Air Force for the USAF Ramey Air Base, had stood since the 1940’s and had become a popular diving spot in Puerto Rico. Maria’s storm surge and flooding has changed the hydrology and layout of a great number of beaches on the island. Another example, La Poza de las Mujeres in Manati, no longer exists, as a river nearby swept away the path and the houses, burying the beach with sediment.

There is an eerie quality to the city after months of blackout after Hurricane Maria, and even more days in some places after Hurricane Irma. It’s a becoming a ruin of the urban landscape, interrupted ever so often by places lit up with generators, or connected to the patched-up grid.

Young plantain trees grow on the side of a hill in Las Piedras. Planted a week and a half before Maria, the crops from these trees will be ready in 8 to 12 months time. Almost all of this year’s crops were lost, ranging from plantain to coffee, mango to quenepas.

In Las Piedras, one unfrozen pancake, 1/4 cup of syrup, and a slice of American cheese is given as breakfast at 3pm. Food aid distribution had been left to the municipalities, causing problems as FEMA and central government aid logistics were not coordinated for the first 3 weeks after the Hurricane. This tray, for example, was give out to feed a family.

Gas cans in the back of a tricycle. Fuel supplies were scarce in the first 2 weeks after the Hurricane, with fuel shortages causing hour-long and in some cases day-long lines as people flocked to stock up.

A little umbrella provides shade and cover to a gasoline generator in Old San Juan. Generators have become the norm for everyday life in post-Maria Puerto Rico, with extension cords crisscrossing streets as neighbors help each to have a fan on and keep the refrigerator during the night.

Improvised lights on the hood of a junk collector’s car. People are picking up all sorts of metal from the streets, from aluminum to cooper, which helps with the immediate clean up but at the same time means the theft of the electrical and telephone lines.

Massive heaps of scrapped aluminum sidings form nearby a recycling center in Santurce.

“Life is cruel” reads a tag next to a closed restaurant in Old San Juan. Small businesses in Puerto Rico have all but been forced to close, as maintaining operations is difficult and costly with no steady electricity and poor telecommunications.

Empty supermarket in Old San Juan. Candy, liquor, soda, and what little nonperishable items were all that was available for 2 weeks, as distribution was interrupted and the generator flamed out.

Cafe Sidibou, a Lebanese/Dominican restaurant, was heavily damaged by the winds and rain brought by Maria. The message reads “We are stronger than Maria! Onwards PR!”

Department stores, such as this KMart in Trujillo Alto, have also become centers for people to gather after Maria. TVs, chairs, and fans have been set up so that people can enjoy a little normality after the storm, as well as offering outlets for them to charge electronics and operate therapeutic nebulizers.

Abner, of Cafe Comunión, sells coffee outside of his coffeeshop. The storefront of his business, which hadn’t even opened, was demolished by the winds and debris.

In Aguadilla, some took to camping and the beach in the immediate wake of the storm.

“There is no power, no water, no communications back home, it’s more comfortable to just camp in a hammock,” said Pichón, a local from nearby Aguada.

With little phone service in the first few weeks after the Hurricane, communication methods were quickly improvised to keep in touch. Here, at Hidrante, we posted notes to keep in touch and coordinate meetings while cell phone service was out.

People waiting in line for dinner at El Local en Santurce. El Local is a punk bar located in San Juan, that serves as one of the main venues for the independent music scene in the city, as well as the neighborhood dive for the young creative class. It has transformed itself into a community center in San Juan, helping people by offering a volunteer kitchen open from 9am to 9pm, free WiFi, and electricity.

A meeting at Beta-Local to start planning the distribution of emergency funds for the creative community in Puerto Rico. Grants given by the Andy Warhol Foundation, Rauschenberg Foundation, and Hispanic Federation have helped them set up El Serrucho, an emergency grant program for cultural workers.

“Against all odds, the art scene in Puerto Rico has strengthened and diversified over the past several years, on the backs of artists, curators, educators and others who take on the responsibility of cultural development in the absence of government support and market viability…Beta-Local is committed to devoting all its resources and tools to guarantee that these individuals and the results of their efforts don’t disappear, and that their recovery contributes to the sustainable transformation of the island.” - Beta-Local

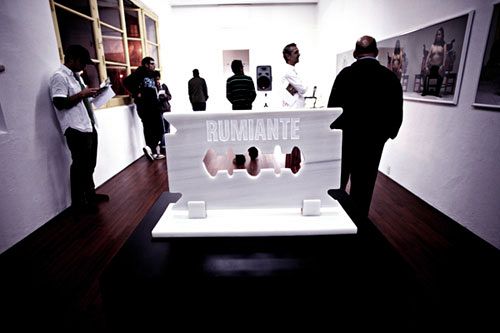

In the background, paper mache heads from the nearby workshop of Agua, Sol, y Sereno. The heads are part of costumes made for the Campechada and San Sebastian festivals in Old San Juan.